Ad [00:00:00] BCNA’s helpline provides a free confidential telephone and email service for people diagnosed with breast cancer, their family and friends. Our experienced team can help with your questions and concerns and direct you to relevant resources and services. Call 1800 500 258 or email helpline@bcna.org.au. Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do, with Dr Charlotte Tottman, brought to you by the Breast Cancer Network Australia.

Kellie [00:00:40] Welcome back to Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do with Clinical Psychologist Dr Charlotte Tottman, Charlotte specialises in cancer related distress and her experience extended beyond that of clinician to that of patient when she was diagnosed with breast cancer three years ago. In this episode, we're going to talk about post-treatment adjustment, which is often overlooked. It includes physical and psychological rehabilitation and what you can expect in the years after the treatment stops. This episode of Upfront About Breast Cancer is unscripted, so some of the topics discussed are not intended to replace medical advice or represent the full spectrum of experience or clinical option. Please exercise self-care when listening, as the content may be triggering or upsetting for some. Welcome back Charlotte.

Charlotte [00:01:29] Hi Kellie.

Kellie [00:01:32] This episode you have titled The Meltdown, which I don't think is going to leave to many of us guessing what that is about.

Charlotte [00:01:42] No, it's sort of self-evident, really. It was a pretty rough ride, so it's about my own experience of post-treatment adjustment, and I'm a really good example of what not to do. So, this is where it's like as a therapist do as I say and not as I do, you'd think I would have known better. So I just to talk briefly about post-treatment adjustment. That's the part of our experience with cancer that happens when hospital-based treatment finishes. So if you've had things like surgery, chemo radio that all comes to a halt and then there's consideration given to things like, you know, maybe going back to work or parenting or study or caregiving. And it's kind of about the time when your brain starts going, Oh, well, maybe I need to reclaim my life and we start to look a bit like we used to and we start doing some of the stuff that we're used to. And so the people around us are very much, you know, getting the message that kind of like all that treatment stuff that's over. And we're kind of like getting back to normal, which of course we are not. And it can be a really challenging time because we can feel a real sense of impatience and urgency and pressure both from within ourselves and externally to get back to that pre diagnosis life. But we're still very much dealing with the very serious side effects and aftermath of all of that physical treatment, but also the fact that our psychological system has kind of been on hold. While that's all been happening and it's like someone takes their finger off the pause button on your psychological system and all of that emotional stuff and all of the implications of what's happened comes roaring at you a bit like a tidal wave, and it's a bit messy.

Kellie [00:03:17] Sometimes it might be worth pointing out that that time frame is different for everyone. Some people go through treatment for months and months, and then you have a pause and go back and have more treatment. You have mastectomies, etc, so it's how long's a piece of string? But that's you. It was actually quite swift, wasn't it, between diagnosis, surgery and you determined to get back to your busy life?

Charlotte [00:03:44] Absolutely. So the only other thing I'd say about post-treatment adjustment is that once it starts or once you finish hospital based treatment, your recovery is at least two years. Your recovery post hospital-based treatment is at least two years. That's information that's often not communicated by the medical system, not because they're trying to keep it a secret. Just because when you are diagnosed, the focus is very much and very appropriately on getting you into treatment and getting decisions made in appointments made and getting you into treatment. So stuff about what's going to happen when we finished treatment isn't really on the agenda, and I quite often find myself in the position of having to communicate this information to people. And a lot of people are quite surprised because they sort of often think, ‘Oh, well, I'll be, I'll be back to normal or I'll be or I'll even be back to whatever the new normal is fairly quickly’, like in the first month or two, and it just isn't like that. My story of this was that I had my surgery in August and in September, two things happened of the same year. Two things happened. One was that I started hormone blocker medication, and the other was that I went back to work. And both of those things were probably bigger than I realised. I didn't credit them as being as significant as they as they were. So in the first few weeks of starting hormone blocker medication and going back to work full time, I was sort of okay. I mean, I actually wasn't, but I wasn't the mess that I became, and it sort of took a while for the hormone blocker side effects to really settle in. What I think we worked out retrospectively with work was that I was still working as I normally would. What Rob my husband was aware of because he works in the same rooms with me was that he said to me, ‘You know, your clients are getting the best of you’, because I was still able to give what I needed to give to work. But what I what I worked out later was that it was taking more of me, so the work that we do is obviously, you know, sometimes reasonably intense, and it does take up your personal resources, but I've got a pretty good big capacity normally and I would just kind of eat that stuff up. What was happening in these months at the end of 2018 was that it was really starting to take its toll was really eating into me. It was exhausting me. And coupled with that as I wasn't sleeping and I didn't realise how much I wasn't sleeping. And this went on for the tail end of 2018, and by the end of the year, I really was very, very, very sleep deprived. And I think looking back now, we worked out that I was probably getting about two or three hours of sleep a night, which is so not enough.

Kellie [00:06:20] I want to ask you, why did you not take time off to start with? Did you think? I'm fine? What were you thinking?

Charlotte [00:06:30] Yeah. What was I thinking? I think that I was guilty of a few things. I think ego was in there. I think I thought like I was different to other people. And guess what? I'm not. I think that I thought my clients really needed me. And whilst that may be true on some level, the truth is that, you know, if I disappeared off the planet tomorrow, the ground would, you know, I close over on top of me very quickly and people would find new psychologists and largely be fine. So I think that I felt I felt like I somehow needed, you know, that indispensable kind of thing. I think that as women, we get a lot of positives for coping. We get a lot of like, You're amazing. I don't know how you do it. You just incredible. You don't get too many positives for being a blubbering mess on the bathroom floor. So I think I probably was, you know, buying into that a bit.

Kellie [00:07:24] You have mentioned before because of your line of work, you have a lot of friends who are specialists in the medical field where they're not giving you a bit of a shake, saying, Charlotte, you need to take some time off and why would you not listen to them?

Charlotte [00:07:39] Yes, my medical team were very frustrated with me, and I think they had tried each of them in their own way multiple times to counsel me to not to return to work or certainly not to return to work at the level that I did. And I was just saying now like, don't worry, it'll be fine, you know, I'm fine and I'll be fine. And I again, you know, I feel a bit embarrassed about the fact that I wasn't taking their advice because they are. I mean, I just I respect them so much and they're my team. But I just felt like I could do it.

Kellie [00:08:15] So you were great at work. How were you at home?

Charlotte [00:08:22] I was a nightmare. Women who've been on hormone blocking medication will probably relate to this when they say, when I say that I, my tolerance was very high. I was a very cranky person. I find this very interesting. If I was two years younger, I'd do a research study into the effects of hormone blocker on intolerance because it's a very specific mood alteration. It's not your whole mood. It just does seem to be around your short fuse. People report being very snappy, very short, getting very upset about things very quickly. So going from zero to 100, very quickly, Robin, I had some very interesting arguments about very important things like chocolate. And so I mean, I look back on that time now, and I just think I just don't know how he hung in there. It was it was a very, very tough time for our relationship. We've got a we've got a good relationship. We've got a good history together. We're a good team. But my goodness, it was it was rugged.

Kellie [00:09:21] Okay, so you've gone back to work, you're holding the tight with your clients. They're getting the best of you. I mean, you're fighting over chocolate and you're not sleeping. Yes. And you've got a short fuse. This sounds like a snowball effect. That's what was heading, basically. What would we physically, because no sleep is not a bad...

Charlotte [00:09:44] Again, looking back, I could see it quite clearly. I couldn't see the wood for the trees when I was in it, but I was just getting more and more and more exhausted. It got to the beginning of 2019 and three physical things happened, which I think was my body's way of going pay attention. You know, we've tried to tell you nicely, but we're going to have to beat you over the head with it. So the first thing that happened was I woke up one morning with this sort of lockjaw situation happening on one side of my face. It just came out of nowhere to this day. We don't know what the cause was. It was the pain was excruciating. It was like someone put an axe through my head. It took at least a couple of weeks and some pretty serious pain medication to get it to settle down. There was some hypothesising about whether it was connected to some of the medication that I had been on for cancer treatment. Anyway, it doesn't matter, we don't know, but that was the first event. The second of. It was we were up at the river and in an effort to reclaim my life, you know, get back and be that person I was before cancer, I was behind a boat and I was on this thing called ‘a wakeskate’, which is just like a sort of like almost like a flat board. You're not attached to it. And the idea is that if you do fall off, you know, it's not like a board where you've got boots in it, where you're going to hurt your knees and stuff. It's quite it's meant to be quite safe anyway. I've been on these things a lot before, and I was out there being that person that I wanted to be and I had a fall and it wasn't a bad fall. It was a sort of fall that, you know, typically I think I would have thought if I had that sort of for nothing terrible would happen. But it so happened that I broke a rib. I've had a fair bit of pain in my life, like I've had four children. So, you know, I know pain, but I tell you what, a broken rib is a whole other thing. So for a person who wasn't sleeping already to then have a broken rib, which really if anyone has a broken rib listening, they'll know that every time you breathe, your eyes just want to like, you know, fall out if they hit your head with pain. That was not going to help with my sleep. So that was the second thing. And then the third thing that happened only a few weeks later was that I got shingles, which is commonly considered to be related to stress. So, you know, don't have to join the dots. It's not too hard to join the dots there. I wound up in my office and he diagnosed the shingles and he, you know, sent me on a course of anti-viral medication. And then he looked at me and I was in my work clothes and he said, ‘What are you doing right now?’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And he said, ‘What are you doing? Are you working?’ And I said, ‘Yeah’ and he said, ‘How much?’ And I said ‘full time’, and he said, ‘I need you to stop that now’ and again, I don't even know if I replied, I don't think I replied, I think I just thought, ‘Yeah, that's not going to happen’. So off I went and another couple of weeks passed. And I think if you were drawing a graph of this, it was just like this just, you know, gradual downward trajectory. I was just like really getting more and more broken and I was feeling shocking.

Kellie [00:12:42] So how many hours of sleep we're getting a night, do you think?

Charlotte [00:12:45] Two or three max. Yeah. So bad. So, so bad. I mean, honestly, if I have clients come in and tell me stuff like this, like it's a very serious situation, a very serious situation. So I persisted with this ridiculous situation. And a couple of weeks later, I broke. And that's when the meltdown happened. So it was a Monday. And back then I used to work at a private hospital in my own clinic, but at a private hospital down south of Adelaide. And I drove down there on the Monday morning and I drove into the car park and it was about half an hour before I was due to start and I just felt so awful. I felt so exhausted, like I just I'd never felt so exhausted my whole life before I went to get out of the car. So like, I started driving the car and then I just shut the car door again and I just sat there and I thought, ‘I just can't do this’. And as a psychologist, you have an ethical obligation to practise when you when you are able to practise and actually be beneficial to your clients. And it was quite clear to me in that moment that I was not able to be beneficial to anybody. So I texted my admin support and said, ‘I just can't come in. Can you please take care of my my clients today and let them know?’ And then I drove to the beach, and I'm not a beach person that's not particularly relevant. But anyway, it wasn't like I was going somewhere familiar. I just I think I just needed to go somewhere where there was this sense of space and I got a takeaway coffee and I took off my shoes and for three hours I walked up and down that beach with the tears just pouring down my face. And I just knew with absolute clarity that I couldn't keep doing what I'd been doing. It hit the wall, absolutely hit the wall. It was gone. It was like when I think about that day, I kind of know, you know, there is some shitty days in your life and getting diagnosed is pretty shitty. But I think this was. I think this is a bit worse.

Kellie [00:14:45] Do you think it was just all so bad catching up with you? Do you think maybe, you know, like you've said before, the psychological pause happens for all the immediate danger to go? And you know you looking after your physical health. Usually looking after other people, too. And you just like treading, treading, treading. And clearly you just got to the end of you.

Charlotte [00:15:08] Yeah, yeah, I really did. I think I was spent, like it felt like I had just I just didn't have anything left, which of course, makes complete sense when you think about it now. My body was literally shutting. I mean, that's extreme, but it was it was sending me messages that I was not coping physically, and that was a lot to do with, I think, the sleep situation. But it was also to do the fact that when I wasn't asleep and I was, you know, in daylight hours, I was pushing myself far too hard.

Kellie [00:15:38] So did you realise in that moment, like was it an epiphany? Oh my God, or was it? No, I just I can't. No.

Charlotte [00:15:46] Yeah, it was. I was just like, I'm broken, like, I am done. And I was a bit scared to, I think because, and I think perhaps only thinking about this now that I was a bit scared because holding on to my life and keeping doing everything I'd been doing was the familiar. It was what felt normal. It felt safe. It felt like, you know, if I just keep doing this, then I don't have to confront everything that's actually happened. And the fact that, you know, everything is different now when I talk about this with clients. I was in this stage of adjustment called resistance, so I was very resistant to the fact that there had been this colossal event in my life and that everything was different. So no, I yeah, it wasn't like an epiphany. It was just like a like a face slam into the dirt. And I went home and I rang my oncologist because I knew she would be placed in a weird kind of way because I said, I'm going to take a break. And she said, ‘Oh, thank God, Charlotte’ and I am so frustrated with myself that it took me getting to that point to do what I counsel my clients to do, which is to take it easy and go back to life in a very graduated, gentle kind of a way that gives you room to process and deal with the psychological and the physical stuff. But I didn't do any of that. Yes, I went home and I sat down with my daughter, Harriet, who was there then, and we made a plan in amidst the floods of tears. We made a plan that I was going to take three months off work. And so that obviously involved a fair bit of fan dangling to set that up and make that happen. But we did it. And god, did it feel like the right thing? I just like every fibre of my being, was saying, this is so that the thing that I need to be doing.

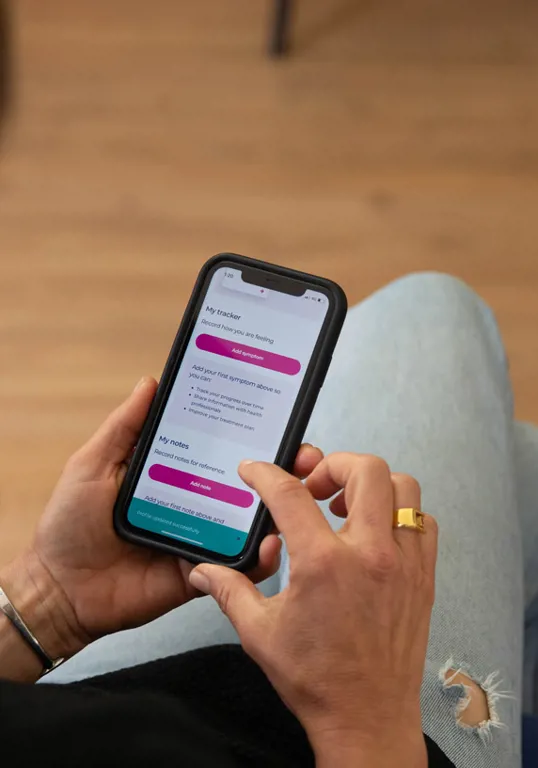

Ad [00:17:47] Looking for practical information to help you make decisions about your diagnosis, whether DCIS, early or metastatic breast cancer? BCNA’s My Journey features articles, webcasts, videos and podcasts about breast cancer during treatment and beyond. To help you, your friends and family as you progress through your journey. It also features a symptom tracker to help you manage the changing symptoms you may encounter during your own breast cancer experience. My journey. Download the app or sign up online at my journey dot org

Kellie [00:18:21] I used to think because breast cancer does have amazing statistics of recovery, particularly early breast cancer, which is what you had. Yeah, and notwithstanding the double mastectomy, do you think we tend to, because of those positive statistics, people downplay it, like you downplaying it like, well, it's early breast cancer, my chance of recovery is amazing. It's just you're somewhat invalidating it, and yeah, playing it down. So you'd almost feel like you don't have the right to lose it?

Charlotte [00:18:54] Yeah, exactly. And I think that again, whilst I totally counsel people about the opposite of this, I think that because of the work that I do, I see people at all stages of a cancer experience and I see people not just with breast cancer. So I see a lot of people in very, very serious cancer situations. And whilst my brain says it's not a competition, and if this is the hardest thing you've ever had to navigate, it doesn't matter what it is. It doesn't matter if it's a cancer experience, it doesn't matter if it's early or late. It doesn't matter if it's a divorce or a being fired from your job or losing a child. It doesn't matter what it is. If it's the hardest thing you've ever had to go through, then it's the hardest thing you've ever had to go through. And it's your body, it's your bucket, and your bucket is full with your buckets full. It doesn't matter what it's full of. So it isn't a competition. And yet maybe on some level I was feeling, I don't know. I didn't. I didn't consciously recognise that then, but maybe on some level it was kind of like, well, it was only early breast cancer. Now I would never in a million years be supporting that sort of thinking or approach with my clients. And yet perhaps I was guilty of that.

Kellie [00:20:01] We're always our own harshest critic, aren't we?

Charlotte [00:20:04] Yeah, for sure. Absolutely.

Kellie [00:20:05] And so you redirected your clients into safe hands and what did you do?

Charlotte [00:20:12] I went to a therapist. That was interesting because even though I talk now about being so clear about the problem with sleep or a big part of the problem, far from all but the big part of the problem is sleep. It's not like we understood that in the moment. So neither Robin nor I understood that my sleep deprivation or insomnia was such a big factor or was at such a bad state. And it was only when I went to see my therapist, who I should have been saying more before then. And this guy I've been seeing since I was 16. So, he knows me very well, and he was so good because he identified instantly that until we got this sleep situation sorted out, basically everything else was still going to be pretty messy.

Kellie [00:20:56] It sounds so simple, doesn't it?

Charlotte [00:20:57] Well, doesn't it? Doesn't it? Absolutely. And, you know, sitting on that side of the fence as a therapist, a lot of the time I certainly have had that experience where, you know, I'm kind of like, ‘Well, that's what we need to get sorted out’. And you can see clients looking at you like, ‘Oh, oh, I didn't realise. I didn't realise, Oh, yes, now that you're pointing it out, maybe that is a big part of the problem’. So he was great and he prescribed some medication to help me sleep. And then I was very fortunate to be able to go away for a month by myself, which was probably really good because I'm not sure what would have happened if I'd stayed at home. It was a really good thing for me to be able to just take some time out. It was like a little bubble and I and I do certainly appreciate that so many people would not have the option of something like this. And I do again, I talk to my clients about it, even if you can only have a day or a weekend to yourself. Anything where you can just get some perspective, get a bit of time away from everybody, look after yourself, prioritise yourself. It can be so therapeutic. And for me, it was a game changer. So I went away for a month, and the three things I did was I exercised and I wrote. And I slept. Not in that order, actually. I didn't intend to write. I'm not a writer but, you know, it's not one of those things I typically do, but I had this pressure, I guess inside of me. I just felt like there was so much stuff I was trying to process all of the stuff that had happened since diagnosis in July. And by now, we're sort of in March, April of the following year. So it's been about nine 10 months, which is still very new, still very new, very new. But a lot of stuff had happened and it felt like I was just this pent up like a coke bottle that had been shaken and I needed to get it out. And so I had my laptop with me and I just thought, I'm just going to write some of this stuff. I'm just going to get some of this stuff out, get it out of my head. I do recommend this to a lot of people. I mean, some people will call it journaling doesn't matter what you call it, it's just about getting it down. And so I started to write and it was really just writing about things that had happened, how I felt, what my thoughts were and getting it all out. And truthfully, it started to take the form. Ultimately, there was a lot of writing of potentially a book and a lot of the material that is in it is actually what we're using for the podcast series. They proved to be kind of really beneficial to me because it gave me a way of being able to make sense of a lot of what had happened and why I was feeling the way that I was. And I think it also gave me the sense that I wasn't going to be stuck in this space forever, that that this was part of a recovery process and like making sense of things and moving forward was going to be really helpful for me.

Kellie [00:23:51] Does it have to make sense, though, when you're when you're writing down, is just literally writing whatever's in your head? A really helpful exercise in itself.

Charlotte [00:24:00] Absolutely. So even if you don't join the dots in that moment, that doesn't matter at all. In fact, I would say to you, there was a lot of that going on for me was just, I was just like getting it out. And it was only, you know, sort of over the couple of years since then that I've gone back and you don't ever have to read it again. Like, there's no rule that says, if you write stuff down, you ever have to read it again. But I have read a lot of it again, and I've made sense of this because I've worked on it since then. But yes, definitely just getting it out can be very helpful. And the other thing that I did on my computer at the same time was I kept a log, a data, what I call it, a data log. What it was just keeping track of what I was doing in terms of exercise, sleep, sleeping medication, what my mood was. I gave myself a score out of 10. I also kept a note of how many fights I was having with Robin on the phone because he wasn't. So at the beginning, it was like two fights a day. And after about 10 days, it was like we were down to no fights and it was like,’ Okay, well, this is good’. Yeah, and I could say that my sleep, which at the beginning was literally like even with medication, I was still not sleeping well at all.

Kellie [00:25:05] I was going to ask you. I find that really interesting. Even just because you have medication doesn't mean that all of a sudden you start no pushing at Z's for eight hours. Do you have to relearn that? And I guess it's like a flow on effect at once. You're sort of taking the external pressures away, increasing your movement. I assume that you're not doing 10k runs when you say exercise and movement. Is it as simple as going for a walk?

Charlotte [00:25:28] That's all it was to begin with. It was just going for a walk. And at the beginning, it was only about 15 minutes. And over the month I kept track of this and it was read. It was so good. It was an accident that I kept track of it. I don't even really remember how or why I particularly started it. But gosh, it helped because I could see that I was making progress and that I was recovering, that I was getting stronger psychologically and physically. So yes, I started with walking. And I had a couple of little tiny hand weights, just like 1.5 kilos each and not at the beginning. But after about 10 days or two weeks when I was starting to feel a slightly human, I started using the hand weights as well. And that was really good for me because my chest is so tight from the surgery, it made me more mobile and made me feel stronger. That was really good. But keeping track of, yes, how much medication I was taking, I was also taking the hormone blocker and I was in a lot of pain. I had a lot of arthralgia, which is joint pain, so I was taking some pain medication. So there was a quite a few things going on and it was really helpful to just keep track of all of that and see the progress that I made. To your point about the sleeping and the sleeping medication, the other thing that sometimes happens when you are really sleep deprived, like sometimes we make the assumption that if I get tighter and tighter, I'll just get more and more exhausted and then I'll sleep better. And that can happen. But the other thing that can happen is the more tired you get, sometimes the more wired you get. So your brain gets overstimulated. And that was definitely what had happened to me, where my brain was like a rat in a wheel and it was going faster and faster over the months that that happened. So it took some time even with the medication and even being away from work and family and life sort of stressors being in my nice little bubble. It still took nearly two weeks for my brain to just feel like it wasn't just going the whole time. And that was a bit scary too, because I think I had thought that if I go away and I take the sleeping medication, you know, the ship will right itself fairly quickly, and it took a lot longer than I thought.

Kellie [00:27:34] And it would somehow, I'd imagine, mask like that ability to keep going in that wide sense gives you that false sense of like, I've got this, I'm OK. I don't need much sleep. I can operate on two or three hours and look at me. Boom, boom.

Charlotte [00:27:48] Absolutely. And not only did it mask it to me, but it masked it to other people because I was all about it. I was getting out there and doing what I do, and

Kellie [00:27:57] You were amazing.

Charlotte [00:27:59] Yes, you're amazing. Is so amazing. You broken, woman. Yes. Yes.

Kellie [00:28:05] Yeah. So a month. Did that fix everything?

Charlotte [00:28:09] No, no, no, it didn't. But it certainly got me to a point where I could recognise that there were some things that needed fixing. I didn't have any insight. So there are three stages to what we call adjustment. Adjustment is a time-based process, and I talk about it as being in three stages. The first is resistance. The second is acknowledgement, and the third is acceptance. And acceptance is one of those words that people bristle at a lot because it can feel like, oh, you know, it's like saying, I'm completely okay with having cancer and everything that's happened. And it's not. It's about accepting that something bigger than you. That's outside your control. Has happened to your life. And I was very, very stuck in resistance. And truthfully, that's what I see a lot in my therapy, in my in my consulting room is people who are at the acceptance point are not in my consulting room because they're out there living a life. But the people who are really struggling like I was with resistance and heading towards acknowledgement, they're often in my consulting room because they're finding it very difficult to reconcile, like what they think they should be doing or want to be doing with what they're actually capable of doing or

Kellie [00:29:14] what society expects them to be doing.

Charlotte [00:29:15] Absolutely. What society, what their family? Yep, all of that stuff. And as women, you know, we are socialised around this idea of doing, of caring, of keeping the family together, keeping the ship afloat. There's not a lot of scope in a lot of women's lives to just step out. Certainly not for a month. That's a really hard thing to do. And so I think that's what we call an exacerbated in therapy. We look for things that are like, maybe not a cause, but they're making things harder, and I think that's definitely one of them.

Kellie [00:29:44] So not everyone, as you've acknowledged, can go away for a month and take a month off. And if it is within that two-year period post, the medical based treatment finished. It's quite often when people have stopped offering help.

Charlotte [00:30:00] Yeah, there can be and often is a real impatience and an expectation in ourselves, but more specifically in the people around us for life to get back to the way it was before diagnosis, because that's what works for them. And so the idea that you kind of still need some time for yourself that you might need a bubble of time for yourself to actually process some of this stuff, and you might need to make some more permanent changes to the structure of your life and therefore their life that can be that can be pretty full on. And so it is about, first of all, recognising it and engaging in it. And that's the stage of acknowledgement where we go, yes, things are different and my life does need to be different to reflect that change. Once you're there, then you can start to communicate it with the people around.

Kellie [00:30:46] You could be hard not to feel guilty, though, when you've already thrown everybody else's life into chaos, with your diagnosis, with your treatment and it's disrupted everybody. And what now you want some time for yourself as well?

Charlotte [00:30:58] Totally. Yep. And women are so good at guilt, so good at mother guilt. So good at that stuff. And so absolutely there is that sense of like, Oh, just like, minimise this, I'll invalidate my experience. I'll brush it under the carpet and you can do that for a while. But I mean, as my experience shows, it's going to come back to bite you in the arse at some point.

Kellie [00:31:19] So like you pointed out, self-care is the first thing that gets damaged.

Charlotte [00:31:23] It should be the last thing that goes. It should be the first thing that everybody in your family is aware of and supportive of. But of course, that won't happen if you aren't recognising that and talking about that and saying, I'm not going to be cooking dinner on Wednesday nights because I'm going to be at the physio and you lot have to work it out for yourselves.

Kellie [00:31:44] So like you pointed out, it might not be a month away, but it might be a Wednesday off. So it's that approximation approximating doing it in small ways if you can't do it in the big ways. So when you get towards acceptance moving out of resistance, did that lead to change?

Charlotte [00:32:00] Yes. So I came back from being away and then I still had some more time off, and that's when I started to actually identify and then communicate to the people in my life. Okay, what am I going to do differently? Because the definition of insanity is keep doing the same thing and expect to. Different result. So I knew I had to do something different otherwise is going to end up right back where I was before. So I recognise that I definitely needed to get the sleep thing. It wasn't sorted, but it was definitely heading in the right direction. I knew that I needed to make room in my life for things like exercise, saying my therapist, going to the physio, going for walks, time away from work, like that work life balance thing. I recognise I needed that, and a lot of a lot of it comes back to time. You know, self-care takes time, and it's the first thing to go when we get busy and stressed. It's the easiest thing to give away because we go, you know, like, I've got to worry about everybody else's needs and that's again what women are socialised around doing. It sounds kind of easy to go, Oh, I just worked out. I need to do all these things, and then I just did them. But it was actually quite hard to then sort of go, okay, if I'm going to, you know, spend half an hour exercising every day, wears a half an hour going to come from. And you know, where am I going to do it and how am I going to do it? And all of that sort of stuff. So I made some decisions and I did communicate them to my husband and my family. And I did make the decision that when I went back to work, I would only go back at 80 per cent of what I was doing, which is still a lot, but it's one less day a week. Big change.

Kellie [00:33:34] Did you do that gradually or did you go back at 80 percent?

Charlotte [00:33:39] No. I went back part time and I built back up from there. So I and I sort of did that a bit quietly, so I was quite strategic about that. I felt like the pressure would be high if I just said, I'm coming back. So I was quite strategic about coming back quietly and gradually and again. This is what I do. Counsel my clients to do is that way you can set it up so that you don't go back full throttle at the beginning. You actually give yourself a chance to work up, get your stamina rebuilt. And that's what I did. And it was the right thing to do.

Kellie [00:34:16] Your resistance phase was fairly dramatic. What are sometimes the more subtle signs of resistance?

Charlotte [00:34:24] I think that sometimes because again, of commitments and obligations that we might have that were there before we were diagnosed, we can use those commitments and obligations as justification for kind of getting back into life the way it was before diagnosis. So things like, you know, I need to make my financial obligations, so I need to get back to work. I don't want to disrupt the children's life any more than it already has been. So I need to get back to all of their extracurricular activities. And, you know, being the president of the Scouts Club and all that sort of stuff, when what that might be masking is an unwillingness to kind of come to grips with the fact that things are not going to be the way they used to be and that some adjustment to the format, the structure of our life is actually going to be a lot more helpful that I see a lot a lot of people will actually say things like, you know, I hate the idea of cancer dictating a change to my life. I don't want cancer to have that much power, and I can really understand that. And I think that was one of my big learnings was that the cancer was bigger than me and I didn't want it to be. I wanted to be the boss of the cancer and that didn't work. And I think a lot of people feel that same way of like, Well, if I get back to what I was doing before, then there's the evidence that I'm in control of this situation and finding out that actually, that's not how it is.

Kellie [00:35:53] And you've put yourself in a race that you simply aren't going to win.

Charlotte [00:35:57] You can't win and you can keep running, which is what I did. And till you are flat out exhausted or you can go, do I really need to do that to myself? Can I maybe acknowledge that this is a big thing that my body and my brain and my emotional system is different now? I mean, if you think about it after cancer treatment, you are from a cellular level app. You are practically, physically not the same person. And the experience that you go through psychologically changes you as well. You can't go back and it might be very appealing to go back there because of course, if we could go back there, then it would be as if this never, ever happened. But the reality is we don't get to do that.

Kellie [00:36:42] What we do get to look for is the new version of you, which is what we're going to discuss in the next episode of Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do with you, Charlotte Tottman. If this episode has helped you, you might like to share it with someone you know and subscribe to ensure you never miss an episode. We'd also love you to leave a rating and review the podcast, and if you have a few minutes, there's a survey in the show notes. It helps BCNA create content that's relevant to our members and their needs don't forget BCNA, My Journey. It tailors information for every stage of your diagnosis. Sign up at my journey dot org dash au and if you'd like to connect with others for support. Join BCNAs Online Network. All the details are on BCNA’s website. A little of what's coming up on our next episode.

Episode preview [00:37:36] You can call it what you like the next version of you the new normal Charlotte 2.0. But it is about embracing, acknowledging, coming to grips with the fact that this thing that was bigger than new has happened. And you can't turn back time. And once you can get to that place and you can actually kind of go, Well, do you know what? This next chapter of my story, my life doesn't have to be better or worse. It doesn't have to be measured against what my life was before. It can just be the next part of my life.

Kellie [00:38:08] Our theme music was composed by the late Tara Simmons, who lost her life to breast cancer with thanks to her family for allowing us to use it in the podcast. I'm Kellie Curtain. Thanks for being upfront with us.

Ends [00:38:24] Thanks for listening to Upfront About Breast Cancer, what you don't know until you do with Dr Charlotte Tottman brought to you by the Breast Cancer Network Australia and proudly supported by JT Reid.

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=384&height=240&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=64&height=64&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

Listen on