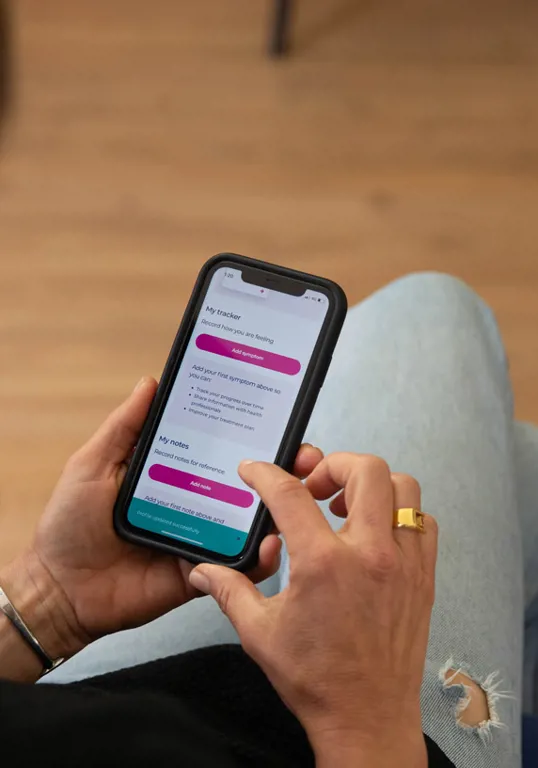

Ad [00:00:16] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Breast Cancer Network Australia. Looking for practical information to help you make decisions about your diagnosis, whether DCIS, early or metastatic breast cancer. BCNA’s My Journey features articles, webcasts, videos and podcasts about breast cancer during treatment and beyond to help you, your friends and family as you progress through your journey. It also features a symptom tracker to help you manage the changing symptoms you may encounter during your own breast cancer experience. My Journey. download the app or sign up online at myjourney.org.au.

Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman.

Kellie [00:01:04] Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer. This is series two of what you don't know until you do with clinical psychologist Dr. Charlotte Tottman, who specialises in cancer distress and who has also had breast cancer. In this episode, we're going to have a conversation about pain, persistent side effects and palliative care. Sounds like it's going to hurt Charlotte.

Charlotte [00:01:29] Painful. I know. Doesn't have to be, though.

Kellie [00:01:32] We're also going to discuss some of the really common misconceptions about palliative care.

Charlotte [00:01:39] Yep. We're going to unpack that.

Kellie [00:01:41] Right. Well, this episode of Upfront is unscripted, and the topics we're discussing are not intended to replace medical advice, nor represent the full spectrum of experience or clinical option. So please exercise self-care when listening as the content may be triggering or upsetting for some. So, the word pain, it's big and it has a real scale, doesn't it?

Charlotte [00:02:06] It does. And even the word pain, I think, sets off an emotional response in most of us. Pain is typically a signal from our brain to indicate that something's wrong, kind of like Houston, we've got a problem.

Kellie [00:02:19] And is the brain always, right?

Charlotte [00:02:21] Interesting point. I don't think we should ever assume that the signal is wrong. But sometimes it's good to understand your pain, your signals, getting to know, kind of what's familiar and common and what you might have been experiencing for some time. And the difference between that and perhaps something that is new and different and perhaps, you know, you're making sure that your response is appropriate depending on which you're dealing with.

Kellie [00:02:58] One of the really difficult things about pain is that it's invisible.

Charlotte [00:03:02] It is invisible. And you can be in, unless you're in kind of that sort of, you know, level of medical pain where if it's not managed well, where you know, where it is obvious where you might be, you know, profusely sweating and you might be making noise and there might be external indicators, you know, like it like you can say that someone's sort of panting and their heart rate might be that high. I mean, that's a very high level of acute pain. But for most of us, a lot of this can be in a degree of discomfort in something we might register and describe as pain, but it can absolutely be invisible to others.

Kellie [00:03:41] What does pain apart from hurting? What does it do for you in real life?

Charlotte [00:03:49] So it usually means that we place meaning on whatever's going on. So, the event, the signal, the sensation, we interpret it as a sign of impending doom. And often that means that we avoid we style what we try and stay away from the thing that is causing the pain. So, if it's, for example, movement or exercise, we might stop doing it.

Kellie [00:04:15] What if you ignore pain?

Charlotte [00:04:19] That can be dangerous and damaging. So, I would never say that you should ignore pain. But again, it is about getting to know your pain and understanding perhaps what your pain is signalling to you. And on that score, I'm not talking about really from a you know, from a medical standpoint, I'm not a pain physician. I'm not a pain specialist. I'm talking about it from a psychological standpoint and not in that way that I think some people might have experienced or heard, you know, that idea of like our pain is in your mind. Not at all. I'm talking about real pain, real sensation. But I guess the differences in those experiences of pain and how we interpret the pain or the feeling and then how what we do behaviourally as a result.

Kellie [00:05:08] Pain is almost certain for anybody who has had a breast cancer diagnosis, whether it be in biopsy, in treatment and things that come with that and definitely in post treatment adjustment. Yep. And for those with metastatic obviously pain becomes a part of that a lot. So, like you said you don't ignore pain but what happens when you've got pain and you know there's no danger, how can you have pain without fear?

Charlotte [00:05:46] I learned about this myself in the last few years, as probably from my experience of my double mastectomy and earlier, a nasty knee injury, which is got nothing to do with my cancer, but the weirdly similar experiences where I learned that at the beginning there was probably what we call acute pain and there was, you know, tissue damage and repair that was required. And there was, you know, rehab and recovery and pain medication and all of that's appropriate, normal. But in both cases, with my knee and my knees, where I shattered my kneecap and my double mastectomy, in both cases, my recovery got to a point where it was as good as it was going to get. And I have nerve damage, which means that in my knee and my chest, which means that I have an ongoing sensation all the time, 24 seven, whenever I'm awake in both my knee and my chest. In my chest, it feels like I steel band around my chest. So, we call that iron bra syndrome. And in my knee, it feels like kind of my knees almost like a concrete block that feels incredibly heavy in both my chest and my knee. You can put a skewer in them, literally. I'm not kidding about this. You can put a skewer in them. And it doesn't hurt me because the nerve damage is so extensive. So, what I've got is this weird situation where they've both recovered, they're both functional. I can move my chest, I can swim, I can, I can't run, but I can walk on a treadmill. I'm developing the ability to squat with my knee. So, they're both as good as they're going to get. They both still have a sensation. But what I've been able to do is identify that in neither case does the sensation signal impending doom. It doesn't mean something more bad is going to happen if I use them, if I exercise, if I move, if I just feel a sensation, it's not a signal of anything bad going to happen. Now, that took me quite some time to work out and what I was doing there, and I've reflected on this long and hard and I use this in my work is I've separated pain and fear and I've been able to go, okay, a sensation in my knee or my chest, plus fear equals pain. If I take the fear out of it, then all it is, is a sensation. Now, that sounds a little Pollyanna, and I don't want to it sounds like that.

Kellie [00:08:10] Lot of wishful thinking.

Charlotte [00:08:11] Well, I know, I know. I get you. And I get that. Absolutely. And I'm very careful when I'm talking about this with clients not to send the signal that I'm invalidating their pain experience because it's real.

Kellie [00:08:24] So do you even though you're labelling it a sensation. Someone else would still call that what you're feeling is pain. Like you feel.

Charlotte [00:08:32] Discomfort? Absolutely. Yep. And I'm very careful now that I know. I think in my mind I use the word sensation and when I'm talking about it, I use the sensation. Now I use the pain in other contexts. I feel I get it now, a pain under my arm I will talk about as pain because it's a new sensation and it has a fear component where I go, Ooh, that doesn't feel right. That needs some attention. I wonder what that's about. That might be cancer related, might be something else sinister. But I so it's not like I'm going all of my pain ever for the rest of my life is just a sensation. I'm not talking about that at all. I'm talking about way you've worked out that you've got something that's got as good as it's going to get. And this might apply to something like peripheral neuropathy, which again is a nerve damage situation that only recovers sometimes, sometimes it fully resolves, sometimes it only recovers to a point.

Kellie [00:09:25] Like lymphoedema too.

Charlotte [00:09:25] Exactly. And you can get to sort of 12 or 18 months and it's like, well, this is how it's going to be now, and we need to find a way to live with it. And so, one of the ways that I've found that I can live with my discomfort the best is to not place the pain meaning on it, not place the fear interpretation on it. And that works well, because then I can get on and do stuff. If I have the fear interpretation, I'm more likely to have the avoidance response, which is to go, Oh God, I better not keep swimming or I better not keep on the treadmill because it's going to get worse. And I've tested this theory and what I found is when I do the avoidance thing, it doesn't get worse, it doesn't get better.

Charlotte [00:10:11] It doesn't get better, it gets worse.

Kellie [00:10:13] Is the polar opposite of that, that every single new pain you had, you rushed to the doctor?

Charlotte [00:10:21] No, because I think particularly in a cancer context and with fear of recurrence, the risk is that we'd all be spending, you know, a lot of time at the door and a lot of money. So, I quite often use the suggestion that, you know, treat your new pain the way you might if your ten-year-old came to you with a pain. If I came to you and said, Mom, I've got a I've got a pain and a pain in my tummy or I've got a sore arm, what would you do? Would you immediately rush to the doctor? Now, in here obviously is an assessment and judgement kind of component, but, unless there is kind of like free-flowing blood or a bone poking out of an arm, most mums would go, let's sit with it for a bit. We might do some at home treatment, so we might do some ice or some paracetamol treatment. Or some rest or some monitoring. And then after a while, depending on what's happening, we will make a judgement call about medical intervention. And I think it's helpful to do that with yourself because if you just do the emotional response, which is often that fear thing of like either avoidance, I'm not going to keep doing the thing that that may be, I think cause the pain or the reassurance seeking which is rushing off to the doctor. Sometimes it's good to sit with it and wait for your rational brain to engage.

Ad [00:11:33] Your first call after being diagnosed with breast cancer can be difficult. BCNA’s Helpline can help ease your mind with a confidential phone and email service to people who understand what you're going through. BCNA’s experienced team will help with your questions and concerns and provide relevant resources and services. Make BCNA your first call on 1800 500 258 or email helpline@bcna.org.au.

Kellie [00:12:04] Okay, so we've got pain without fear equals sensation. Even when you've found out that there's no fear or there's no link.

Charlotte [00:12:17] Between pain and fear.

Kellie [00:12:19] If you like. Yeah. Sometimes we need pain medication. Yeah. And there's a bit of a stigma associated with the need to have

Charlotte [00:12:29] Pain medication and medication. And so, this is in those instances where you might be dealing with a situation where the pain can be relieved, whatever, whatever the sensation is, your feeling can be relieved, reduced by pain medication. And pain medication, like a lot of things, is good when it's prescribed and used as indicated by your medical team. There is still quite a lot of stigma around the use of pain medication and there's been some research done in the last it's probably been in the last 20 years around the fact that the stigma around pain medication has actually, in some cases caused people to use vastly less than they really should and had exactly the opposite effect of what we want, which is to then leave people in more pain. And there's this concept that I describe called the pain trough, which is where when people feel like I don't want to be a junkie, I don't want to use more medication than necessary, I don't want to be going back to my doctor and getting more prescriptions, that they stop taking the prescribed amount of pain medication and then they fall into the pain trough. And the pain trough is essentially where you feel all of the pain, all of the pain that you could possibly be feeling. And then in order to get out of the pain trough, you end up having to take more medication than you would have if you had continued to take the medication at the prescribed amount and interval.

Kellie [00:13:57] Yeah, so it's not just the stigma to sometimes people don't want to take pain medication because they have a fear of getting addicted or so they become reliant.

Charlotte [00:14:08] Absolutely and dependent for sure. And you know, most pain medication is prescribed with those exact kind of four warnings. And there's, you know, guidance and caution given by medical teams around. You know, this stuff is heavy duty, and we want you to be responsible. But responsibility kind of works both ways. You know, too much is not great at all and for too long, but also nor is not enough and not for long enough. So, I think it does come back to, as with most things, communication. If you are in contact with your medical team and doing what they prescribe, you are likely to have the best outcome. Now that that doesn't always happen. But I think that if you're going to moderate your pain medication, if you're going to take control of it and reduce it, the best thing you can do is to be doing that in discussion with someone with a medical degree so that you aren't just making a decision based on perhaps an emotional state from an emotional standpoint, which might be that, you know, I don't want to be dependent or I don't want to be a junkie. I wanted to be considered a junkie. So again, that's FONEBO - fear of negative evaluation by others. I don't want to be judged by others. And so, I think being really mindful about this because that that pain trough experience is real and you can end up then again, it's that whole thing I've described before. You end up getting more of what you don't want. You end up having to take more pain medication than you would have otherwise if you had just continued to take it as prescribed.

Kellie [00:15:41] And this is possibly not an issue for those that need very temporary pain relief. Yeah, but it becomes possibly a bigger issue when it is for either metastatic disease or for something long term. Like neuropathy.

Charlotte [00:15:57] Yeah, absolutely.

Kellie [00:15:58] Like lymphoedema.

Charlotte [00:16:00] Yep. And learning about your pain and learning what helps and what's going to sit well with you and having those discussions with your medical team is important because just blind faith and following, you know, someone else's direction. If it doesn't feel like it's going to sit with you, particularly if it's going to be for a long time, that's not going to work and it's going to mean you're not very likely to do it. And of course, then you then going to be more likely to be in more discomfort for longer.

Kellie [00:16:30] Okay, What about persistent side effects? Quite often they need medication. quite often they're for the long haul. They last a very long time.

Charlotte [00:16:42] And quite often, just like pain, they're invisible.

Kellie [00:16:45] So you've just possibly had surgery and gruelling treatment, a bit of pain you might undermine and go, well, hey, that's nothing compared to what I've just been through. And it might almost feel a little bit whiny, briny to go, you know, I've got this pain. You don't want to bother people who are very busy or with doing lifesaving stuff to address what might seem in the big scheme of things, quite small.

Charlotte [00:17:17] I think a lot of the persistent side effects post-treatment or for example, the persistent side effects that come with things like hormone therapy, they happen after that hospital-based treatment, you know, that happen when you are not in a hospital setting. You're not in saying your medical professional every week or every few days. And there is that sense of like I'm meant to be, you know, reclaiming my life. And I'm meant to be kind of like getting it together. And yes, I don't want to be complaining. I also I don't want to necessarily be defined by, you know, a whole lot of medical staff. You know, I do want to be me now and not be me just always kind of like reflecting or going on about all of my side effects and the need for medication and intervention. The types of side effects that we're talking about that persist often in addition to things like pain and lymphoedema and peripheral neuropathy can also be arthralgia, which is that joint and muscle pain that often comes with hormone therapy or the lack of oestrogen essentially mood changes. You know, it's funny to talk about mood as a side effect, but that's a reality. Mood changes in connection with hormone therapy are very real and particularly noticeable around what we call intolerance. So having a sharper temper or a shorter fuse. Fatigue, very persistent long term side effect after cancer treatment. Cognitive changes, often people will report both as a consequence of things like chemo and radiation, but also in relation to hormone therapy that they don't feel as cognitively sharp as they used to. And if they used to feel like they could kind of juggle a few cognitive balls at once. So, a bit like multitasking in your brain that they just don't feel that they can operate that way, that they feel like they can only operate more in a linear fashion. So, I can think about and handle one thing at a time, but I can't kind of juggle those balls. Hot flushes are a big thing that most people on hormone therapy or in low oestrogen, so chemically-induced menopause experience and things like and this is probably the one space where you might see something is where you have perhaps nail, skin and hair changes again, due to low oestrogen. So that's where maybe somebody might notice that you perhaps look a little bit different.

Kellie [00:19:37] Persistent side effects. If you take each one in isolation, it's possibly manageable, but quite often you get lots.

Charlotte [00:19:46] They come and always come as a little collection. Yeah, a little.

Kellie [00:19:49] Package, which over time can be a very heavy burden.

Charlotte [00:19:54] Really heavy burden. And again, you know, most people in I think in the Noncancer world, if you like, are nonetheless familiar with terminology like surgery, chemotherapy, radiation treatment, that sort of stuff. But I'm not sure that there are that many people who are familiar with either the long-term side effects of those treatments or the side effects that might come with things like hormone therapy. I just don't think people know it's not widely discussed; it's not widely spoken of. And because they are largely invisible and because I suppose a lot of them are effectively menopause, but it's menopause on steroids, if you like, then there's a tendency to kind of like either not be very interested in them or perhaps even possibly be a bit kind of dismissive of them or diminishing of the impact. And that's really invalidating for people going through it. It makes them continue that feeling of emotional isolation.

Kellie [00:20:50] And emotional isolation can lead to physical isolation and really affecting your quality of life.

Charlotte [00:20:58] That's right. Because if you feel like the people around you really don't get it. But if you also feel like your physical side effects limit your ability to join in with the sort of activities that you might have once engaged with, with family and friends, then you may literally disappear a bit from life. You might not be going for those long, fabulous hikes in the national park. You might not be staying up late because you have to get your sleep. You might not be enjoying the same quality of relationships because you might have turned into a bit of a snappy Tom. And so all of those things are real and people can feel it acutely and then, you know, withdraw.

Kellie [00:21:43] And then there's the big swing of like, I have no right to whinge about this because I've got my life.

Charlotte [00:21:48] I've got my life and I have to be so grateful, and so, so grateful that I've got my life. And and I think the other thing too, is that it can feel like what is whingeing, do you know, does it improve the situation, does it make the side effects any less. I mean, I used to develop this little line that I would say to myself, and I'd to this day, I'm not sure it was very helpful, but I used to say, better to be alive, to complain about it. That was kind of like where I got to with hormone therapy because it was like, okay, this is odd. And I needed a way to wrap my head around, you know, living with it. And I suppose, you know, objectively it is better to be allowed to complain about it. But that also felt pretty isolated.

Kellie [00:22:30] And again, back to people who don't get it, you haven't been there. That I get it. So, what do you suggest to your clients when people come to you and say, I know it sort of seems a little bit on the lower scale, but yeah, I've put on a lot of weight with treatments and I just.

Charlotte [00:22:47] Yeah, I'm struggling. Yeah. So, one of the things I suggest is that people use a rating scale for some of their side effects. So, the reason for this is that when we describe how we're feeling, we quite often use verbal descriptors. So, we'll use words like if someone says you how you are feeling and you say, terrible, or how are you feeling, just like I was last week. But that doesn't actually give all that much in the way of accurate information, because what is terrible to me, may very well be different, that word terrible might mean something different to somebody else. So, we get what I suggest is, is that you use a rating scale of 1 to 10. So it might be that if I'm thinking about my arthralgia, how much pain I've got in my joints, in my and my muscles that each day at about the same time. So, it might be when I wake up, it might be just before I go to bed that I just take note and think, okay, what would I give it at a ten today. And so, what that does is it introduces a range and light and shade into that experience because sometimes it feels like it's always the same, like it's bad all the time. And what we find generally is that nothing stays the same, that things do ebb and flow, and that whilst you might not have a day where you have no arthralgia, you probably don't have the same level of discomfort every single day. And being able to reflect on that is helpful for you because it introduces that idea that like, gosh, it's been a pretty good start to the week. You know, maybe it was only if you do the scale at 0 to 10 where zero is perhaps no discomfort and ten is the maximum discomfort. And let's just say at the beginning of the week, it's like, well, maybe Monday and Tuesday were a 3, you know, and it's got to Wednesday and it's getting up there. It's getting to a 4 or 5. But gosh, compared to last week where it was kind of an 8 for most of the week, this is better, you know, so it gives us a way of being able to.

Kellie [00:24:42] It's tangible. Yeah, it's.

Charlotte [00:24:43] Tangible, It's measurable. The second thing that's really helpful is that it gives you a way of being able to communicate the differences to the people around you. Again, I did this with Rob with particularly with my chest and my knee, because it all sort of looked the same and I was kind of operating the same. So, there's not really any visual cues to him as to whether it felt any different. So, I would then say, you know, like it, and I still do that now. It's like a you know, it's bothering me. It's about a 4 or 5 out of 10, and it's very helpful to be able to do that. And it's interesting when you when people do it, how much their loved ones connect with them around that because it makes sense to them, and it gives them a way of being able to respond appropriately. So, if someone's gone from a 3 on Monday to an 8 on Thursday, it's like, whoa, like what's going on? What are we going to do about that? Whereas if it's kind of like, you know, I just feel terrible, there's often not much of a response.

Kellie [00:25:40] Mm hmm. Just to clarify, your knee has nothing to do with your breast cancer.

Charlotte [00:25:44] No, my knee has nothing to do with my breast cancer. But I often reflect on my knee because I guess for a couple of reasons. One, because I learnt what my body was capable of, like my recovery after the knee, which was a really bad accident. My recovery after my knee taught me that I could recover. And that's been actually sort of ghastly but helpful. But the second thing is I find that what I experience with my chest is so similar to what I experience with my knee, and I guess maybe what that makes me feel is that then this stuff is bigger than cancer. Like, so this these experiences are not just specific to cancer. You know that if you've had some other sort of like health event, that this stuff is still relevant.

Speaker 2 [00:26:30] And also can give you hope that you're not always cancer person. Exactly.

Charlotte [00:26:34] And that not everything in my life is to do with cancer that it might be to do with recovery, or it might be to do with my interpretation of things. And so that I don't have to always have it be all about cancer. The other thing when you ask me what else helps.

Kellie [00:26:50] If you say exercise

Charlotte [00:26:51] Yeah, sorry. So sorry.

Kellie [00:26:56] No movement. We should say movement.

Charlotte [00:26:57] We should try exactly...

Kellie [00:27:00] It doesn't mean running five kms, it means doing something.

Charlotte [00:27:06] Correct. And to that point, one of my clients had been seeing an exercise physiologist, I wish I'd got the person's name because I really would like to be able to acknowledge them, you know, more accurately. But anyway, the specialist said to them, I'm going to give you a set of exercises to do on good days and I'm going to give you a set of exercises to do on bad days. And I thought, that's so clever, because essentially what that means is every day, you're going to do something, and it gives you the flexibility. And I love flexibility. It gives you the flexibility to go, you know, I'm having one of those 8 out of 10 days. I just can't do what I would do on a 3 out of 10 day, but I'm going to do something. And so, the exercises are tailored titrated, we say, to be able to acknowledge and incorporate how you feel on a bed. A tougher day. This is on a on a good day. And I really like that because it's too easy. As we've discussed in other episodes, it's too easy when you're feeling tired or overwhelmed or stressed or sore to just go, you know, I won't do that today.

Kellie [00:28:17] So it really is. I mean, quite often it seems to be the pattern of resisting that pain or what that pain means or what that pain doesn't mean. And then acknowledgement of that pain.

Charlotte [00:28:29] Yep and if it's an acceptance, if it is pain that you're going to be living with or if we use my distinction about pain and fear, if it's going to be a sensation that you're going to be living with long term, separating the pain and fear, accepting a level of sensation in your life and working with it.

Kellie [00:28:50] So we've got those distinctions, you know, pain that doesn't have another meaning attached to it. Yeah. Pain which requires medication and can be medicated. And then we have the next level, which is palliative care. And palliative care is usually in most people's minds somewhere where you go for the final stages of life.

Charlotte [00:29:16] Yes. And that is the common interpretation of palliative care. And I don't think I've probably met anybody who has had a kind of really positive reaction to the words palliative care. If I mention the words palliative care in therapy, usually people blanch, you know, they sort of like you can see the whites of their eyes. You can see them kind of like take a breath. And that is because I think we kind of a quite palliative care with death and dying. Yeah.

Kellie [00:29:43] But I think kind of I think we just do. And it is one part. It is definitely one, but it is it is not only, but it is one part. And there are some truly wonderful parts about palliative care that everyone should be aware of to not only educate ourselves, but to help ourselves. Because once you can have someone do something about that and the whole thing that we're going to talk about now is palliative care in managing pain.

Charlotte [00:30:12] That's right. In managing pain and managing particularly those discomfort, side effects of advanced disease and of any lingering treatment side effects from all that disease and treatment. Palliative care is about palliating symptoms, which means it's about relieving the impact of those symptoms. End of the impact of disease when treatment no longer is working. So typically, people will get introduced to introduced to the idea of palliative care when they've got to a stage in their cancer experience that active treatment isn't working anymore. And that might be through the suggestion of their oncologist or their GP, could even be their psychologist who says, Look, I think now might be the time that we need to consider palliative care.

Kellie [00:31:03] And this is about optimising someone's quality of life, palliative care, which in the context of pain that we're talking about, it's about giving that next level of attention and possibly medication to reduce or omit that pain.

Charlotte [00:31:22] Absolutely. And it's not just for the person who's going through the cancer experience, it's for their loved ones in terms of like, what we see is that when someone is in discomfort and struggling with pain, that their loved ones are also going to be likely discomforted and distressed. So, everybody benefits from the involvement of palliative care in bringing down the discomfort level, getting people as comfortable as they can in whichever environment they choose to be.

Kellie [00:31:52] In palliative care. It's not something that people usually go and do a tour of.

Charlotte [00:31:59] No, although I do recommend that, I do quite often say to people, do you know what the difference is between a hospice and a hospital? So just to expand on that. Hospices are the environment, if you like, that if you choose not to stay at home through the delivery of palliative care services. The alternative is a hospice, and a hospice is like a hospital, but different. Often, they're attached to hospitals, sometimes they're not, and they are generally more comfortable, comforting environments. So, they have more natural light, they have more fresh air, they have opening windows and they have big spaces dedicated to family and friends being able to spend extended times. So big kitchens where you can actually prepare a meal rather than a cup of tea. And areas for children to spend longer periods of time because most of us would have had the experience of children in hospitals not being a terrific mix. And often the rooms in hospices have got a better set of furniture available for loved ones to spend extended time. So, it might be reclining chairs that open up to be more like something you could perhaps nap in. Sometimes they even have, you know, pull out sofa bed type situations so that loved ones can sleep overnight and be in the room with the person who's in the hospice and there's less stainless steel. So, they've got the medical stuff available. They've got medical equipment available and obviously medical staff available, but it doesn't have the same smell or clinical kind of appearance that a hospital does. And that's really comforting if you're feeling like, you know, I got I can't stand the idea of being kind of like in a hospital type environment for an extended period. And I don't want all those beeping machines and clanging stainless steel. Well, it's not likely to be like that. Not the way that a hospital is.

Kellie [00:33:48] And the difference between palliative care and a hospital is that in palliative care, they're there to care, not cure.

Charlotte [00:33:59] That's right. And the staff who are working in a palliative care setting are often people who have been doing it for a really long time. There's very low staff turnover in palliative care. The people who work in that space are often very dedicated and it's almost like a calling. And so that's really good if you're receiving services from them because they really know what they're doing, and they are very dedicated. And that means that the quality of the experiences is usually exceptional. I mean, I don't think I've ever had anything other than exceptionally positive feedback about palliative care that staffing and the services generally.

Kellie [00:34:36] I can vouch for that too, just in personal experience. They really are not only, like you said, a calling, but also that's their daily.

Charlotte [00:34:45] That's what they do.

Kellie [00:34:46] That's what they do.

Charlotte [00:34:47] And they don't do anything else.

Kellie [00:34:48] They know their stuff and they and they get it. Yeah. I think it's also worth pointing out that palliative care can be offered in the home, too. And the other misconception is that it's a one-way street like you're going in one end and

Charlotte [00:35:02} like you're never going to come back. If people do say, you know, we think if a part of the medical team says, look, we think we might want to pop you into a hospice for a while, even before they get to finish the sentence, like why people will often react and be like, no, no, no, no, no, no. Because it can feel like if I go in there, the door only works one way and that I'm not going to come out. Now, you know, let's not be naive about that. That does happen. But we do often suggest people going into hospice for a period for pain management to get pain under control. And the reason for it is, is that the hospice environment is a controlled environment. Robyn and I were reflecting on this. Rob, my husband, also clinical psychologist. We're reflecting on this and remembering that when I was in treatment and I was at home and we went anywhere near needing palliative care, but we were having to manage medication and we were having to manage pretty like opiates, narcotics, you know, pretty serious stuff. And the way to manage it was to keep track of it. We had like a clipboard, like Nurse Robin. But what we found was it was quite hard. It was quite hard to keep track of what we were doing because he wasn't the only other adult in the house. And if other people were involved in looking after me and if I was involved in looking after me, keeping track of what medication I had and when I had it, and what other things were going on with me in terms of like, you know, how my bodily functions were and how mobile I was and other things like risks of infection and so on. That stuff is really hard to manage, and particularly if you are not a medical family, like if you're if this is not your bag.

Kellie [00:36:33] And sometimes families are complicated, and they have other commitments. So as much as you might like to have palliative care at home. Sometimes it's just not possible and it's not good for anyone.

Charlotte [00:36:45] No. And sometimes you can end up doing kind of like a hybrid, where you do a bit of both. So, it's not to say that if you do hospice that you can't do home or you at home, you can't do hospice, you can do kind of a mix of both. But I think understanding that what the hospice provides is that controlled environment where the staff can manage the medication, get on top of pain, work out exactly what is needed, and then hopefully send you home with a pain protocol that then the palliative care team working at home with your loved ones can do is make sure that you get what you need. But also, if appropriate, educate your loved ones about how to assist in dispensing that medication.

Kellie [00:37:24] And they really do become part of your team, don't they?

Charlotte [00:37:26] They really do. And that it's a relationship-based service. Once the idea of palliative care is floated, generally what I recommend is that the sooner you get connected with them, the better, because you get to know them, you get to know them on a first name basis and these people are much more available. It's not a Monday to Friday, 9 to 5 service. They're available a lot more than that, and they are able to assist with a regime of medications that is not just what your standard GP would have on offer. So, they are able to assist with high level narcotics that help manage discomfort.

Kellie [00:38:01] And as you said, it's a different skill set. And the sort of bizarre thing is that tapping in earlier can actually not only improve your quality of life but extend your life.

Charlotte [00:38:15] Absolutely. Because if you think about we were talking before about pain and the negative effect pain can have on you, that can happen psychologically and physically. If you think that you've got a bunch of kilojoules or resources in your system that you need to spend. So that's your energy per day. If you're spending most of that energy per day on managing your pain, on coping with your high level of pain, it literally isn't available to do anything else. So, it can't repair, rebuild, cope with anything else, which means that it is possible it will affect not just the quality but the length of your life because you don't have the resources to keep going. Pain wears you down and being more comfortable gives you more resources to allocate to other things.

Kellie [00:39:02] Thank you. Pain without fear and a conversation about fear and about your expectations and what can and can't be done.

Charlotte [00:39:12] Yeah.

Kellie [00:39:13] Can be a good starting point, isn't it?

Charlotte [00:39:14] Yeah, absolutely. And avoiding it, which is the thing that we commonly do with anything that causes discomfort is not going to be helpful in terms of managing the pain, you know, whether it's that sort of chronic pain that we were talking about with my knee and my chest, or whether it's about more managing the sort of discomfort you might experience with advanced disease.

Kellie [00:39:37] Thank you, Charlotte. And we hope that you've found this discussion of use and has provided a greater understanding of pain without fear, pain, persistent side effects and palliative care. Perhaps you might like to share this episode with someone else and we would really love you to rate or review and tell us what you enjoyed. It's helpful for BCNA to create the content that our community wants and needs. And in our final episode of this second series, ‘What You Don't Know Until You Do’ with Dr. Charlotte. We're going to discuss a topic that many find confronting death and dying.

Charlotte [00:40:16] And if the temptation is to maybe, you know, jump ship now. What I would say to you is we've got you this is tricky territory for a lot of people but trust us and we'll talk about it together.

Kellie [00:40:30] We will. Thanks to our podcast sponsors, Sussan. I'm Kelly Curtin. It's really good to be upfront with you.

Ad [00:40:41] BCNA’s Online Network is a friendly space where people affected by breast cancer connect and share their experiences in a safe online community of support and understanding. Read posts, write your own, ask a question, start a discussion and support others. You're always connected, which means you're never alone as our Online Network is available for you at every stage of your breast cancer journey, as well as your family partner and friends. For more information, visit bcna.org.au/online network. Coming up in episode ten of Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. The inevitable: Death, Dying and Mortality.

Charlotte [00:41:26] We don't have a lot of practice in this space and anything that is new and unfamiliar. We've said before that anxiety rises with the unknown, the unfamiliar and the uncertain and death and dying has got all of those in spades. So, it absolutely provokes anxiety. And then we have that very common response, which is to avoid love and grief for mirror images. And so, you know, the reason that we feel so sad about someone dying is because we really, really care. We really, really love them. And that's pretty fab. If you.

Kellie [00:41:54] If you avoid communicating, it leaves space for assumptions.

Charlotte [00:41:58] And it prevents us from having the good experience that might come from the conversation. What we often do, and this is how anxiety works, is it makes a prediction and it basically anxiety says if we go to that space, if we have that tough conversation, it's going to go badly. I'm going to get upset, my family is going to get upset. And we don't perhaps go beyond that and think, well, sure, I mean, yeah, I'm not going to say that it's going to be easy, but you'll come out the other side, you will survive that conversation. And it's probable that there will be benefits from it. And so, by not doing it, we don't give ourselves the chance to experience the benefits.

Ad [00:42:37] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Sussan. Our theme music is by the late Tara Simmons. Breast Cancer Network Australia acknowledges the traditional owners of the land and we pay our respects to the Elders past, present and emerging. This episode is produced on Wurundjeri land of the Kulin Nation.

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=384&height=240&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=64&height=64&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

Listen on