Voiceover [00:00:08] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Breast Cancer Network Australia. Your first call after being diagnosed with breast cancer can be difficult. BCNA’s Helpline can help ease your mind with a confidential phone and email service to people who understand what you're going through. BCNA’s experienced team will help with your questions and concerns and provide relevant resources and services. Make BCNA your first call on 1800 500 258 or email helpline@bcna.org.au. Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman.

Kellie [00:00:56] Hello again and thanks for joining us on Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. In this episode, Charlotte's going to explain the common perspective and experience of partners.

Charlotte [00:01:12] Yes, the perspective of people who often feel like they're the runner up.

Kellie [00:01:16] A reminder that this episode is an unscripted conversation with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. The topics that we're going to discuss are not intended to replace medical advice, nor represent the full spectrum of experience or clinical option. Please exercise self-care when listening as the content may be triggering or upsetting for some. Charlotte, the partner, forever the runner up. It's tough.

Charlotte [00:01:43] It's really tough. In this episode, I am using a lot of material from conversations with my husband, Rob, and for those of you who listen to Series one and particularly Episode eight, which was about learning new dance steps, you might be familiar with Rob. And for those of you who haven't listened to episode eight, it might be helpful to go back and listen to that. We are going to touch on some of the experiences that we cover there, but that episode is a lot about the intimacy side of a partnership and the effect that cancer and cancer treatment can have on that. So back to Rob.

Kellie [00:02:17] Should I just say also that you're talking about Robin, but when we're talking in partner, we're talking any partner, same sex etc?

Charlotte [00:02:25] Yep, absolutely. It could be a long term partner. It could be like a marriage, could be someone that's relatively new, but someone who's been there as your partner through your cancer diagnosis and treatment and often, you know, still with you in the aftermath. So when I said to Rob, could you describe like just in one word what it was like going through cancer diagnosis and treatment with me? He paused for a while to think about it, but he just said it was really hard. And then I said to him, okay, well, if you had to describe in one word how you felt, what would that be? And he said, Helpless. And again, broad generalisations and gender stereotyping. My apologies, but Rob's a middle aged bloke and a lot of middle aged blokes are really used to being able to fix things. Rob's a clinical psychologist, but also as a younger person he was very sporty, so he's used to being able to kind of use his physical form to, you know, achieve positive outcomes. He's a very handy bloke and so he can fix lots of things practically. And in the cancer context he wasn't able to fix anything. And he found that watching me go through something was a really emotionally challenging time for him, you know, as well as obviously for me.

Kellie [00:03:45] And as we said, no matter what sex a partner is, when you were in a relationship or a partnership, you usually work through things together to tackle issues. And the fact is neither of you can actually fix this.

Charlotte [00:04:01] That's right. And usually neither of you have got any experience with this sort of stuff. I mean, Rob and I are both clinical psychologists, we're not stupid people you know, we've got lots of qualifications

Kellie [00:04:10] I really hope not considering we’re doing this podcast!

Charlotte [00:04:15] But I've got to say, in the in the realm of my diagnosis and treatment, you know, we were both floundering. And even Rob said to me this morning, he said, you know, we were not the poster couple for this stuff. We did we did not do this well. And we are not a good model for other people to follow.

Kellie [00:04:32] But that's where this is going to be great, because hopefully others will benefit from your hindsight experience or as we say in just about every episode, it's about awareness being the first step, isn't it?

Charlotte [00:04:46] Right, exactly. And understanding that that if you're feeling that this stuff is hard, you are not alone and it is normal, and that sometimes it is about just endurance and holding on, holding on through the process and holding onto each other.

Kellie [00:04:59] So we often talk about the shock of diagnosis. That's obviously not just for the person who's been diagnosed. That is very much for usually your number one person, which is your partner, and there's no time to prepare it literally happens overnight. So your partner goes from being your partner to your possible carer as well.

Charlotte [00:05:22] Yeah. And sometimes they're in the appointment where the diagnosis is delivered and sometimes they're not. But either way, there's usually no warning. And so just like there's no warning for kind of the bomb going off in your life, there's no preparation. No one gets to, you know, get handed a job spec three months in advance and go, right, I'm going to make these adjustments to my life. I am going to build in time and extra energy and coping so that I'm ready to deal with this when it happens. That doesn't occur. Whatsoever. You literally walk out of a doctor's consulting room and it's game on. You are not just partner and not just carer, but both. So you go into this situation where we have dual relationships, where you've got two things going on rather than one. So you might be husband and wife or partner and partner, and carer and patient and that is a new dynamic and no one usually spells that out and it becomes obvious over time often where there is some friction and tension that bubbles to the surface.

Kellie [00:06:30] It's the real double whammy isn't it? because you've got, like you said, dual roles, but you've got one resource down being the person who is diagnosed and isn't able to do all the stuff that they usually did.

Charlotte [00:06:40] Yeah and then you've got one demand up. So like Rob found all of the needs in our life, all of the domestic stuff, all of his work stuff, all of the family stuff that that didn't change, that didn't go away. So he had to juggle all the balls that he was normally juggling, and then he had to care for me and all of the practical stuff that came with caring for me, but also all of the emotional stuff that he had going on, his fear and uncertainty about what we were dealing with now and how that was going to impact us going forward. So it is it's a really that double whammy effect of being more than one thing to your partner, but then also having to carry the load when they're not able to. And it's not acute, it's not for a week, it's usually four months and it can be for years. And as bad as it is in an early breast cancer situation, it's I think, even more challenging in a metastatic context because it has to be integrated into your life and it has to become part of your normal. And that burden sits with both the patient and the carer.

Kellie [00:07:48] And it's no one's fault that this has happened, but the reality would be that the needs and wants of the person with the cancer has to come before the partner/carer, so their needs become secondary, don't they?

Charlotte [00:08:07] They do, and I don't think there's a relationship that I've seen where that doesn't happen. And again, it's nobody's fault. The spotlight is very reasonably on the person with cancer and I think for a lot of the people going through the cancer experience, that's kind of where they need the spotlight to be too. They need to feel like they've got all the support and scaffolding that they can possibly get their hands on around them to keep them in as good a shape as they can be through treatment and afterwards. And their focus is on survival and self-protection. It's not a lot on how my partner is coping. And sometimes I talk about this using an analogy, like I call it dominoes, where if the person with cancer is the first domino and they lean on their partner, well their partner needs somewhere else to lean because they can't lean back on their partner, they can't lean back on the person going through cancer they need to lean somewhere else, and if they can't find somewhere else to lean another domino, if you like, the risk is that they fall down. And we can't have that because if that domino falls down, then the person going through cancer hasn't got anyone to lean on. So it is really hard being the partner who becomes the carer and I think most partners, particularly in early stages, are not even slightly interested in having this spotlight on them. You know, they are genuinely highly motivated to protect and look after their partner. I think with time sometimes that can change where people can feel burdened and fatigued and possibly even a little resentful by the fact that their needs are always coming second. And that is where, just like we've talked about in other episodes, conversations are really important and sometimes it can be conversations with your partner, the person going through cancer but often it will be more important to have conversations in a safe space with a trusted other person. So it might be a close friend, it might be a therapist, might be a GP, but having somewhere where you can actually express some of that fatigue and frustration and maybe the fact that, you know, you feeling like your needs are just not getting any air time is really important. It's funny how it doesn't seem to make much sense. The idea that if I express my frustration and say out loud that I really need some time for me or I need someone to give a crap about what I'm going through, how can that possibly help? But it does lighten the load just saying it out loud.

Kellie [00:10:50] When people are focussed on trying to assist someone with breast cancer and pick up the slack for want of a better term, and they don't take self-care, how can that manifest? Like sometimes it can become frustrating. You can become perhaps emotionally reactive.

Charlotte [00:11:11] Yeah, absolutely. And I know that when I was really struggling in post-treatment adjustment and I was on hormone therapy and I was emotionally reactive, Rob, too, was emotionally reactive. And we were not a good combination. And I said to him recently, you know, did you feel like you looked after yourself or made time for yourself? And he said, No, no, he didn't. And he understands that that probably played a part in his ability to cope with may not coping. And so it was not a good combination and that when we don't exercise self-care, when we don't make time as the partner, we don't make time for ourself, when we don't look after those four pillars of coping that I've talked about before- sleep, nutrition, exercise, activities with purpose and meaning, then there are real consequences. Now, when I say to Rob, Well, why didn't you look after yourself? He said, ‘because there wasn't any time’. Like you can feel almost impossible to carve out time for yourself. And I use the oxygen mask analogy in relation to this, which is where for those of you who've been on an airplane, you'll be familiar with the flight attendants standing at the front doing the safety demonstration and they'll hold a yellow mask and say in the unlikely event of an emergency, this will drop from the holder above your head. And then they say please fit the mask on yourself before assisting others. And the reason they say that is because if you're not breathing oxygen, you're not going to be any use to anybody else. So if you're not okay, you can't support someone else. And that's a thing that I remind both partners and people going through cancer, because for the person who's going through treatment, they sometimes don't see that. You know as I said before they’re quite reasonably focussed on their own wellbeing and their own needs. And it can slip their mind that actually in order for their partner to be most supportive and most helpful, their partner actually does need to be looked after as well.

Kellie [00:13:14] Active treatment is somewhat of a mindset. People have a start and usually a predicted finish line, so it's almost like, okay, this is this is the bit that we've got to get through. Quite often after active treatment and we talk about the post treatment adjustment, the visual cues start to disappear. So the hair grows back or you starting to get a little bit back into re-entry and life with a little bit of normal activity. Is that also when partners might become a little bit more not oblivious? Whereas they're very happy to put their needs and wants on hold through treatment but now it's sort of like, okay, we need to shift a little bit and I'm talking really about intimacy.

Charlotte [00:14:17] Yeah, absolutely. And I think that's a really good point because during treatment, there are some medical reasons why, you know, you can't be intimate with someone going through chemotherapy, that sort of thing. But I think there is a much greater latitude in relationships to go, you know, during this like six month period you don't look like you want to even think about sex, I'm not sure I would want to have sex with you when you're looking and feeling like that because we want to look after you. And everyone's quite peculiarly comfortable with that. But then, in post treatment adjustment we're starting to kind of get the show back on the road, as it were. And there can be, as I've said before, enthusiasm in everyone for things to get back to normal, whatever that is, and even to create the new normal. And even if that is the idea of like we discussed previously, of learning new dance steps in an intimate context, that's a new and interesting place to inhabit. Rob said to me that he certainly was conscious of the fact that during post treatment adjustment when I was on hormone blockers, that he knew that everything had changed for us in an intimate sense. And whilst he was accepting of that, it didn't change the fact that he still had needs and his needs weren't just physical, he had emotional needs as well. And I wasn't meeting any of those. I was an absolute nightmare to live with and he was aware that I was being affected by hormone blocker treatment and I was also struggling with my own insecurities with body image and needing reassurance. He said to me he was also needing reassurance, just like I wanted to feel like I was still desired and desirable, he also wanted to feel like he was desired and desirable, and I wasn't giving him that, and he didn't want to put that on me. He said to me, ‘I didn't want to be a sex pest’. He didn't want to be rejected but he also didn't want me to feel pressure and he didn't want to hurt me, he didn't want to cause me any discomfort or pain. And we talked about in series one about why sometimes sex doesn't feel the same because of the impact of things like hormone blockers, but also because we might not be in the same headspace that we were pre diagnosis and so all of this stuff plays out in a way that is often not discussed. And you know I asked him, ‘did we talk about this?’ And he said ‘no, we didn't really talk about it then because everything was so heightened and everything was so hard that the idea of having another difficult conversation at the time, even though intellectually we both know as clinical psychologists that talking about stuff is the thing to do but that didn't feel like it was going to be helpful.

Kellie [00:17:16] And it's not one universal experience, is it? Other people will see issues in different parts like there's different levels of intimacy and levels of expectation. Is it possible that sometimes it's changed forever?

Charlotte [00:17:35] Yeah, it is. And that's a pretty big thing to confront. I mean, I know for sure that our sex life will never go back to how it was pre diagnosis, and neither of us are happy about that. We have learned some new dance steps and we've figured out a way to remain physically, intimately and emotionally connected. And I think it's working pretty well, actually now that we're four years down the track. But I certainly have clients where the resolution of it isn't that good and that people do disconnect physically and emotionally. They might stay in the marriage, in the partnership, they may remain committed to the family and they may remain committed to one another, and they may love and care about one another, but not in a sexual or an intimate way anymore. They may be able to effectively co-parent and manage the ebb and flow of life but if there is a disconnect and if they still have needs, it can mean that sometimes those needs are met elsewhere.

Kellie [00:18:44] And you and your husband did seek some professional help for that. It's not always going to work for everyone. I mean, cracks have appeared in the house, if you like, so what do we do, bulldoze the house?

Charlotte [00:19:01] Rob used that analogy and it's so good that, you know, sometimes in a mature relationship, you can think about it like an old house and even if there are cracks that are there in that old house, in that relationship, and depending on the environment, the climate, those cracks will sometimes open up and sometimes they'll close up. And sometimes you even need to bring in someone to help you with some repairs. And yeah he came with me to see my therapist and we were talking about that experience recently and Rob said to me that he didn't even feel safe to really speak in that session. Now, that doesn't mean it wasn't worth him coming in fact, it was essential that he came because it was a signal to both of us, to each other, that we were in trouble and we needed some help and that we were both investing in the relationship. And it was, if you like, a form of a recommitment to figure out how we were going to get through this storm. So him sitting in that therapy session with me and my therapist, even if he didn't say much, was incredibly valuable. And do you know what? When I think about it, I don't even know fully what we did talk about or what my therapist and I did talk about nut I sure remember Rob being there. I sure remember that, and to me that was a really big positive. That was evidence that he was holding on, because I was not holding on to us. He was holding on to us. And if he hadn't, I'm not sure what would have happened.

Kellie [00:20:32] It must be very difficult for a partner to sit and have those desires of what they need and what isn't happening to them. I can understand Rob's resistance in wanting to speak up because it's not intentional that you've landed in this position and it doesn't matter what he says, cancer is always the trump card isn't it?

Charlotte [00:21:01] That's right. Absolutely. And that's the thing, it's sort of the unspoken trump card. And you as the partner, I don't think you necessarily want to have it spoken because it's kind of like ‘I know that I'm living not just with Charlotte anymore. I'm living with Charlotte and the cancer card’. And I don't think I play the cancer card or I like to think that if I do play it, I am very, very, very, very discrete and careful about ever playing it. But it's always there. And I think that's what a lot of partners feel, is that whatever they experience, no matter how big or hard, that unless it is cancer, that it kind of doesn't count or that it's not as bad. And even if that's not what they're explicitly getting back from the person who's been through cancer, it does sit in the room. It sits in the relationship in a very unhelpful way, I might say.

Kellie [00:21:57] Which must then lead to someone feeling invalidated and isolated.

Charlotte [00:22:03] Yeah, really isolated. I talked again with Rob about that and he said, yes, he did feel isolated. And we've talked about emotional isolation in the last series a lot and how when people do feel emotionally isolated, whilst it can be really helpful to step forward and be vulnerable with loved ones and seek emotional support. But if you are looking for it and it's not there, or you attempt to get it and you don't (and that's what happened to Rob), he attempted to get it from external sources and it didn't work. Then you feel really hurt and you feel really unwilling to go and do that again. And he is stereotypically a middle aged male, he says he does not like being vulnerable. But he made himself vulnerable, he stepped outside his comfort zone and it did not go well. He did not get the support he needed so he scurried back inside his comfort zone and said, right, well, I'm staying right here now, I am not doing that again. And of course, where that left him was feeling very isolated. And when I was being a witch, and I was, I was a witch for months... He also says that he didn't share with other people because he was protecting me. He knew that if he shared how difficult I was being, that people would judge. So he had FONEBO (fear of negative evaulation by others), but he kind of had FONEBO for me so he wanted to protect me and therefore he had to shoulder that additional burden for months when he was worried about us, he was worried about me, he was worried about the cancer and he was feeling like he was swimming in a sea of uncertainty in all types - the cancer stuff, the marriage stuff, and he wasn't able to feel like he could share that safely with anyone.

Kellie [00:23:54] And just a reminder that for now, FONEBO stands for fear of negative evaluation by others

Charlotte [00:23:57] Yeah, so the perception of someone judging you negatively. He was worried that if he told other people that Charlotte is just out of her mind with distress, but also, you know, unreasonable and reactive, that they wouldn't get the context and that they wouldn't have the generosity of spirit that we might like to think I was due.

Kellie [00:24:24] And it's also worth noting that whilst we can have a laugh now about Charlotte the Witch and how intolerant and very unlike you, at that moment you couldn't see it.

Charlotte [00:24:38] I couldn't see it at all. And I certainly couldn't hold on to anything other than myself. Like I was having a really hard time just continuing to operate, just to be alive. That was quite enough. And I don't want to over play that, but I also don't want to pretend it was anything other than horrific, it was easily the worst time of my life.

Kellie [00:25:01] But it was also in the post-treatment adjustment period during hormone blocking therapy.

Charlotte [00:25:08] Yeah, it was the first year after I finished hospital based treatment and it went on for a long time.

Kellie [00:25:12] Which is also, again, without the visual cues, you'd gone back to work, everyone was possible thinking we're a year on, Charlotte’s back and nothing to see here, the danger has passed... And yet for you that's when things went absolutely pear shaped.

Charlotte [00:25:35] And it had been hard for Rob from day one, but that was when it got really, really hard. And again, no one knew. So again ,do not do as we did, do as we say!

Kellie [00:25:54] So, were you in denial, the two of you? Would that be fair?

Charlotte [00:25:58] No I don’t think so,

Kellie [00:26:00] Just unaware?

Charlotte [00:26:01] I think we were just in survival mode. I think I was just trying to hold onto me and Rob was trying to hold onto us. I don't think it was denial, I think it was just a catastrophe, it was just a nightmare.

Voiceover [00:26:17] BCNA's Online Network is a friendly space where people affected by breast cancer connect and share their experiences in a safe online community of support and understanding. Read posts, write your own, ask a question, start a discussion and support others. You're always connected, which means you're never alone as our online network is available to you at every stage of your breast cancer journey, as well as your family, partner and friends. For more information, visit bcna.org.au/onlinenetwork.

Kellie [00:26:52] So we're talking about the cancer card, how it always tends to win. It's always going to be at the top of that tree. It makes me think of not only just that fatigue we were talking about, but also the unintentional score card that we all keep.

Charlotte [00:27:08] Yeah, and we talked about that in series one where in relationships we do a bit of scorekeeping and not even realise we are doing it and we only realise we’re doing it when we start to say, you know, this is what I've done or these are all things you haven't done. So just like the cancer card, that scorecard can sit in the relationship sort of silently and I think it can operate both for the person with cancer and for the partner, but in different ways. So for the person with cancer, it might be that they keep track of all the ways that they feel you haven't been there for them, and they might hold on to that for a really long time. And perhaps for the partner, it can be a scorecard of all of the things that I have been doing, all of the things that I've been doing to support you, to keep the show on the road, keep the household and the family running, and maybe all of the things that I feel like you perhaps haven't noticed or acknowledged or even said thank you for.

Kellie [00:28:01] That sounds like a big argument in the making.

Charlotte [00:28:04] Well, it can be. And I think, again, awareness is really important because if you are nursing that scorecard, then sometimes it's helpful to clear it or to proactively get it out on the table as opposed to waiting for it to reactively blow up in your face.

Kellie [00:28:26] So we've recognised that it's tough and the need for carers to put on their own oxygen mask. How can they do that in reality? We've noted that quite often, whether it's through unacceptable waitlists or a reluctance to seek medical intervention or professional psychological help. And I'm reluctant to say go for a walk! But what are some of the other helpful ways that people can fill their cup so that they can go back to being the best version of themselves.

Charlotte [00:29:01] Yeah, for sure. Look, sometimes it does sound a bit diminutive, but I was going to say exercise. But I think particularly for partners, I think exercise where there's a social element. So it might be a kick of the footy at the park even with the kids. So something where you feel like you’re a bit more you. It might be connecting with people who you have good, trusting, possibly long term ties. So stereotypically again, it might be a beer at the pub on a Friday night. Now if you're the cancer person and your partner says I'm going to go to the pub with my mates this Friday night, that might not sit all that well with you. You might perceive that or misinterpret that as perhaps a self-indulgent behaviour on the part of your partner who's supposed to be loving and caring for you. And it could be that, but it could also be their way of being able to download and get support in a very stereotypical male-blokey way. But you know, that doesn't mean it's bad or wrong. It might be just the way that works for them. Now, that's not the same as saying I'm going to the pub with my mates every night or I'm not interested in your cancer treatment and side effects and situation. So it is about understanding the context a little bit and thinking about, okay, what might be a way of me understanding that my partner needs time and space for themselves.

Kellie [00:30:31] As we've said with self-care of the person who has cancer, that has to be their priority- fighting the cancer and getting well again, or finding the new way to exist and integrate cancer. That often means whilst there's plenty of offers of help from external sources, it really relies on the partner to become captain of the ship if they weren't already which quite often means that they're going to do things differently to you.

Charlotte [00:31:04] Absolutely. And Rob reflected on this because...Oh, am I a control freak!? Have I been a control freak!? Probably. And we've been a good team over the years. He's always been very hands on in terms of parenting and domestics and life admin. But when I was in treatment he had to take on everything. So for a control freak to be sitting back and watching somebody that can feel a little bit uncomfortable that they're not doing things the way that you think they should be done. And this comes back to that rigidity that I've mentioned before where, you know, if we think there's only one explanation for things or only one way to do things that can feel very uncomfortable when we have to confront the reality that maybe there isn't. And so Rob certainly found that there was a little bit of pushback from me, especially when I was in witch mode, about if he was going to run the show, I had to accept that he was going to do it his way and that did not always go smoothly.

Kellie [00:32:05] And that could also come across as being ungrateful for that extra stepping up that they're already doing.

Charlotte [00:32:13] Exactly. It's like what? You're going to micromanage me now? So, you know, I think I can probably work out how to cook dinner or pick up the kids or pay the bills or whatever. But now you're going to tell me that I have to do it the way that you've done it for the last 20 years? And yes, it can come across as ungrateful and unnecessary at a time when we've already got enough trickiness in the situation that we're living with. We don't really need to add that in. But again, you know, awareness is the key here. And this episode is as much for the person who is going through cancer as it is for the partner, because I think one of the things that we do as the person going through cancer is we self-protect, put ourselves in our own little bubble and we go ‘I'm just going to worry about me. I'm given lots of messages that this is completely okay and required for me to prioritise all of my needs’ and I'm not going to argue with that. But if you want your relationship to weather this storm the best that it can, having at least one ear or one eye open occasionally to the reality that this is having a very probably a significant impact on your partner is going to be helpful.

Kellie [00:33:23] Charlotte, what do you suggest to clients who are feeling frustrated by their partner's lack of understanding or perhaps the diminishing of their partner's understanding, particularly in that post-treatment adjustment period.

Charlotte [00:33:40] I think that as ever it comes back to communication. And sometimes when we're living with the cancer experience and we're thinking and feeling it all day, every day, we can slip into making the assumption that the people around us are similarly just as aware of things like the side effects or the lingering fatigue or the fact that my brain doesn't work the way that it used to, or that I'm scared about the future. If we don't put language around that we prevent the people around us from understanding our position. The other thing you can do is that you can, and you need to be careful about the language that you use in this, but you can ask your partner ‘Hey, how are you going? But also how do you think I'm going?’ Like actually ask them for their perspective. I quite often write this on my whiteboard where it's a three step thing- It's How are you? How am I? How are we? And that's quite cool because it gives each of you the opportunity to reflect on how you are, so I'm important, and how I think you're going, so again each of you then feels important because you're feeling like the other person's thinking about me and it gives you the opportunity to gently correct. So if somebody says ‘actually I think you're doing really well’ and then you go ‘oh, that's fascinating, because I feel shocking’. And then ‘how are we?’ it's like you talk about your relationship. So, you know, actually we’re probably not doing as badly as we were a month ago, or gosh we have been at each other like cats and dogs this week, I wonder why? And so just three questions. How am I? How are you? How are we? and each of us responding to those can be a really helpful way to tackle it.

Kellie [00:35:27] That does sort of sound like you're going to possibly go down a rabbit hole. Is it helpful to set a time limit and try to ensure that it doesn't turn into a huge thing?

Charlotte [00:35:38] Yeah, I think if you've got to the point either of you as the partner or the person with cancer, where you are either wondering or worried about where things are at in the relationship, it can be good to flag a schedule signpost to set up a time to talk about how you're going and even ask the other person if they'd like to. So you might be saying something like, say things are getting a little bit tricky, shall we maybe have a chat about it? Do you want to go for a walk on Saturday morning, just for perhaps half an hour? So what you're doing then is you're giving them the chance to say yes or no. You're scheduling it so it gives them the chance to start thinking about it so you both come to the conversation prepared, and if you say for about half an hour, then your time limiting it. And the message there is this is not going to be a DNM (long, deep conversation), this is not going to be a weekend talkfest, this is just a check in on our relationship. It also says I care. So they're very simple things that can make a big difference versus walking out of the bedroom and going ‘so I've been thinking...’ That is often what we do and quite often does not go well because the other person may not be thinking about the relationship. They might be thinking about the lawns or they might be thinking about that bill that's overdue. They might not be anywhere near ready for a conversation about the relationship or ready to be vulnerable with you right then and there. And that then can set off what feels like not mattering, not caring or rejection when they go ‘what are you talking about?’ Whereas scheduling it, giving them permission to say yes or no, time limiting, it all makes it much more doable.

Kellie [00:37:31] What happens when one person does the classic ‘I'm fine’.

Charlotte [00:37:37] Yeah, ‘fine’ I think in the Italian Job movie was referred to as freaked out, insecure, neurotic and emotional. So ‘fine’ is one of those things we call a social ritual when people ask ‘how are you?’ And we just say ‘fine’ and people are quite happy with fine, because that's sort of what they were going for a lot of the time. They don't necessarily really want to know how you're doing. And within a relationship, if someone is saying they're fine, if you're feeling there's a bit more going on than that and you get a ‘fine’ response, that's a good time to go ‘are you sure?’, dig a little deeper. If you accept the ‘fine’ when somebody's just giving you that very quick, simple throw away response, if you accept that then they probably won't tell you anymore.

Kellie [00:38:32] What about recognition and validation? How far does it actually go for you to either as a partner or as the person with cancer to recognise and validate and express gratitude?

Charlotte [00:38:49] I think that ‘thank you’ and ‘sorry’ are probably the two most underused words in the English language and I am just as guilty of that as everybody else. And probably because of the work that I do, every couple of weeks I have one of those moments where I'm sitting talking with a client and I think, Oh God I'm the worst wife in the whole world and then I send Rob a message. And I actually did it this morning because I was coming to do this and, you know, we'd been talking about this episode and oh, I sound like such a dick when I say this but anyway... I sent him a text message and said ‘you're my hero’ because I don't do that enough. You know, I don't acknowledge him enough, I don't say thank you enough, I don't say sorry enough and I think, how much does that cost us and how much time does that take? Not very much. And how much credit does it buy you? You know, it's like the MasterCard ad, it's priceless. So that sort of stuff is really, really important and I think when we're feeling overwhelmed or vulnerable or resentful or aggrieved, those little words can feel very big and very hard to actually articulate. But boy oh boy, when you do it, usually for the recipient it feels pretty great but I think even as the person delivering it actually makes you feel like a better person, makes you feel like, I do care and they do matter and maybe this isn't all as catastrophic as I thought it was.

Kellie [00:40:27] Does it count as a text message?

Charlotte [00:40:28] Yes, I think it does. I used to think it didn't. I was so sort of superior when text messages started, I was like, oh, I'm never going to use text.

Kellie [00:40:37] Is that a bit like, you know, a handwritten note was so much more proper than just a phone call to say thank you.

Charlotte [00:40:43] Exactly. It's like the whole etiquette around social interactions has changed with technology. But I mean, I send text messages to clients who've lost a loved one to express my condolences. In a blue moon did I ever think I would do that. But that’s actually using technology in a really good way I think. Look, is it the same as saying it face to face or holding someone's hand or putting an arm around them or leaning on them? No, it's not the same as that.

Kellie [00:41:11] It's better than doing nothing.

Charlotte [00:41:13] Better than doing nothing. Or if you're in a hospital bed or if you're at work as the partner and your partner is at home in bed with side effects, it's certainly better than nothing because it comes back to the mattering thing. It comes back to thought of in the middle of a busy day, in the middle of all of the stuff that they've got going on, either as the partner or the person with cancer. In the middle of all of that, they still cared enough to let me know that I matter to them. And that's really, really cool.

Kellie [00:41:41] Charlotte you've obviously had a lot of reflection, both you and Rob, of how you might do things differently. What could you share with others to assist?

Charlotte [00:41:52] So Rob said that if he was asked by someone else for his takeaway, it would be to think about it as being in a bomb shelter where there's a whole lot of stuff going on out there that you can't control and it doesn't feel safe. But in the bomb shelter, you still are mostly safe so the threat is not imminent to you. And how do you get through that period? Well, you protect yourself the best you can, you lean on your mates and you don't pretend that it's easy. That is probably something that if you are a partner, it is probably worth just thinking about it in those terms as a way of being able to get through what is a really tough gig for everyone. There's one other part I guess that people do ask me about and does happen in my therapy room, and that's if things get really tricky in a relationship during cancer or after cancer treatment. So when your relationship really hits the rocks, what do you do? And my number one piece of advice is no big decisions. No big decisions when you are in the thick of treatment or even if you are in a mess of post-treatment adjustment like Rob and I were. Because if we'd made a decision based on Charlotte the Witch, I don't know where we'd be now. So no big decisions is a really fundamental piece of advice with a waiver. And the waiver is that of course if you are in a dysfunctional, toxic or abusive relationship, then that needs consideration. So I would never say that I want people to stay in a relationship that is of that quality, but that needs special consideration, particularly if you are the person going through cancer treatment because the idea of leaving a relationship in the midst of such a huge medical crisis is not a small one in terms of what it's like when your relationship hits the rocks. Nobody wants to be the person who leaves the person with cancer. I've had that in my consulting room quite a number of times, and mostly it does result in years later the relationship ending. But people do tend to buckle up and hang in there for the experience of the cancer treatment and even the aftermath.

Kellie [00:44:08] Because it's a traumatic experience and people sort of hang in in trauma don't they?

Charlotte [00:44:12] Yeah and I think that partly there's that sense of I don't want the social disapproval that might go with leaving someone. But I think there's also often even in a relationship where the relationship might not be working anymore, there's still an element of care and respect and wanting to not pull the rug completely out from under someone who's already going through plenty. But it can be an incredibly hard thing to navigate. And if you think about divorce and separation on a totem pole of stressful life experiences, it's about number two. So if you've already got a cancer treatment experience going on in your family, adding in a separation and divorce is really adding a massive amount of fuel to probably what is an already big bonfire. So the smart play is to recognise, perhaps acknowledge that things are not where we need them to be and we might need to talk to somebody and we might need to develop some real world strategies about how are we going to get through the next couple of months and possibly the next couple of years while we just survive this current crisis and then we can figure out what to do next.

Kellie [00:45:22] For those who don't have a partner or are in a fairly new relationship. Is there any hope of being able to navigate this type of experience when there's no runs on the board if you like, there's no investment already.

Charlotte [00:45:40] Yeah, because we've talked about that before where if you're in a mature relationship or a committed relationship, this kind of already been that commitment, even if you never really expected to have to honour it. But there's been that commitment for better or worse, in sickness and in health. And that's where I'll tell my Muffin Man story. So I have this lovely story from one of my clients, Naomi, who's very graciously giving me permission to tell the story. So Naomi was going through cancer treatment and had the unexpected and I suppose overall and unhelpful experience of having to navigate a marriage breakdown while she was going through cancer treatment, and she came out the other side of that. She's got a little boy and the two of them were living in the family home together in ongoing treatment because Naomi's being treated for metastatic disease and she needed some stuff done around the house. And at this point in her life, I think she was probably considering that it was more likely than not that she might not re-partner and that she might not enjoy a relationship again. And I don't know that she was necessarily devastated by that, but it wasn't filling in a cup, as it were. Anyway, she needed some stuff done around the house, and so she called a handyman. And the handyman came and she gave him some jobs to do. And he was out in the shed and she thought, I don't know what the etiquette is around cups of tea and coffee and what have you with handymen. But anyway, I'll go and offer him one. So she offered him a coffee and she quite liked the look of him and so she found herself wondering maybe whether she should be offering something more like maybe a muffin. So she whipped up some muffins and took a hot muffin out to him with his coffee. And the rest, as they say, is history. And she's been in a relationship with a lovely man who was aware of what he was getting into when he partnered up with her. And I'm not going to say, and I think I'm right in saying this on Naomi’s behalf, it's not perfect. Nothing's perfect. But it's real and it's a relationship. And it's with a person who loves her and her son for everything that she is, including her metastatic cancer. And so I guess what that does give us is evidence that this stuff does happen and usually it happens when you’re least expecting it.

Kellie [00:48:04] The opportunity to step up.

Charlotte [00:48:05] Yeah, exactly.

Kellie [00:48:07] Thank you, Dr. Charlotte. I want to thank you, because it's important to say thank you. We hope you found this episode of Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman helpful. You might like to share this episode with a partner or someone else that might find it helpful. And don't forget to write or review our podcast and tell us what you enjoyed. It really helps BCNA provide content that you want and need. Thanks again to our podcast sponsor, Sussan. I'm Kelly Curtain. Join us in episode eight where Charlotte talks boundary setting.

Charlotte [00:48:51] Yes I do, and ‘no’ is a sentence!

Kellie [00:48:53] You've been listening to Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. Join us next time.

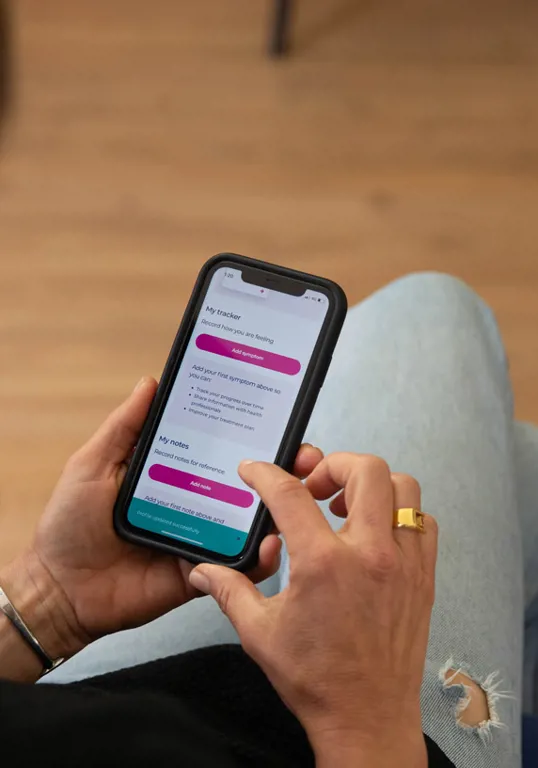

Voiceover [00:49:03] Looking for practical information to help you make decisions about your diagnosis, whether DCIS, Early or Metastatic breast Cancer. BCNA's My Journey features articles, webcasts, videos and podcasts about breast cancer during treatment and beyond to help you, your friends and family as you progress through your journey. It also features a symptom tracker to help you manage the changing symptoms you may encounter during your own breast cancer experience. My Journey, download the app or sign up online at myjourney.org.au. Coming up in episode eight of Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. ‘No’ is a sentence: Boundary setting.

Charlotte [00:49:50] And I think women in particular are socialised around saying yes, about being agreeable, about going along to get along and subordinating their own needs. So that means putting their own needs below the needs of others, particularly the needs of loved ones. And so it can feel foreign, counterintuitive, like you're breaking a social rule or like you're breaking your own rules to start saying ‘no’ when you maybe haven't had much practice of doing that, or if you have on occasion tried and it hasn't gone very well because people around us don't necessarily like a boundary or a limit being set where there hasn't been one before. And so again, there can be pressure to go back to the way things were and the people who are likely to act out the most are the ones who have the most to lose from you setting the boundary. So if you're not going to always be available, or if it means therefore that they're going to have to pick up some of the slack, or even just if they have to rearrange their thinking around this, that can be enough for them to push back against it. And go why? and why do you get the right to do this?

Voiceover [00:50:59] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Sussan. Our theme music is by the late Tara Simmons. Breast Cancer Network Australia acknowledges the traditional owners of the land and we pay our respects to the elders past, present and emerging. This episode is produced on Wurrundjeri Land of the Kulin Nation.

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=384&height=240&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=64&height=64&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

Listen on