Ad [00:00:08] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA). BCNA’s Online Network is a friendly space where people affected by breast cancer connect and share their experiences in a safe online community of support and understanding. Read posts, write your own, ask a question, start a discussion and support others. You're always connected, which means you're never alone. As our Online Network is available to you at every stage of your breast cancer journey, as well as your family, partner and friends. For more information, visit bcna.org.au/onlinenetwork. Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman.

Kellie [00:00:56] Hello. You're listening to Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do. The second series is Unlimited and has been made possible with thanks to Sussan. I'm Kelly Curtain and I'm with clinical psychologist Dr. Charlotte Tottman. And in this episode, we're going to talk about the re-entry wobbles, getting back into life after cancer treatment.

Charlotte [00:01:19] And it can be wobbly.

Kellie [00:01:21] It sure can. Charlotte's going to explore some of the challenges in the experience of re-entering things such as work, study and other commitments. The common drop in self-confidence and the importance of purpose and meaning. A reminder that this episode of Upfront About Breast Cancer is unscripted and the topics discussed are not intended to replace medical advice or represent the full spectrum of experience or clinical option. So please exercise self-care when listening as the content may be triggering or upsetting for some. The wobbles when people get back in the game Charlotte.

Charlotte [00:01:58] Yes, it's that time of life after cancer treatment ends, after hospital based cancer treatment ends and we've talked about it in the first series under the heading post treatment adjustment. And it's usually in the months and years that follow the end of that really hardcore treatment or for people living with metastatic disease, it's finding a way to, you know, integrate their health situation into their work and their other commitments. So it's reclaiming life and it's best done in a way that accommodates what you've been through. And the fact that for at least the first few years after diagnosis and treatment, you are in that recovery rehabilitation mode and it can be wobbly, it can be tricky because people are often pretty enthusiastic about getting back in a way that is as close to how it was before diagnosis.

Kellie [00:02:55] When someone is diagnosed, it tends to happen fairly quickly. One day you're during the school pick up or one day you're at work and then all of a sudden you're not. And whether it's through direct communication or otherwise, people find out that the reason you're not around is because you have had a cancer diagnosis. It's not so clear on the way back, is it?

Charlotte [00:03:22] No, it's not. And just on the point about, you know, who gets to know what, I think definitely in this episode it's probably helpful for us to distinguish between a work and community obligation context and maybe family and friends context. Because I think when we think about who gets to know what, probably family and friends are going to know about the cancer stuff, it's not a given that information will be communicated fully or accurately in the work or maybe volunteering or study. Those people may not all get the same information. And that might be because you choose not to give it to them, it might be because you might work in a very big workplace and only the people closest to you might know the actual details of what's gone on for you. And I think that difference is important because when you go back into those spaces, what people know informs often your feelings and often your anxiety about how you're going to be received. So if you know that you're going back into an environment where everybody's up to speed and they know what's happened and how you've coped and you know where things are at now, that's very different than the last time you having seen someone was maybe sitting in a meeting and then you just disappeared for a year and you've got no idea how much they know or if they know anything.

Kellie [00:04:46] And that's right, isn't it? Because with family and close friends, you're likely to see people throughout that treatment, whereas in, you know, a couple of circles outside, whether it be work colleagues or wider community, it is quite feasible that you actually haven't seen these people for quite a long a long time. Let's break it up, shall we, into work and community then. So you're re-entering the game after your cancer treatment, how do you tackle that?

Charlotte [00:05:20] Often we see a really significant drop in self-confidence. So self-confidence is underpinned by a thing called mastery, and mastery is underpinned by repetition. So things that we do frequently and a lot of we get mastery in. So we develop skills and then we develop confidence off the back of being able to execute those skills successfully. So when you are living a life and you have lots of practice at your workplace or your study or your volunteering organisations and you do the same sorts of roles and responsibilities, over and over again, week in week out, you get comfortable and confident with that and that's all good. When you step out of those situations and you're out not just for a week, but with a lot of cancer treatment, you could be out for months or even for a year or two. You stop doing those tasks, those roles and responsibilities repetitively, and that can mean that you lose confidence. I experience that not in the work context, but I think I referred to this in series one where I stopped cooking and even when I was going through treatment and even now when I step back into the kitchen, I'm a really good cook and I cooked for six people for 40 year but I feel really like my confidence has suffered because I just don't do it as much. So my repetition has lowered and therefore my mastery has lowered and therefore my confidence is lowered. So I think what happens is people go back into the work environment and they want to be their old selves. They want to be that person they were before cancer diagnosis and treatment. And they are bothered pretty reasonably by the fact that they don't feel like the same person and they don't have the same confidence to do the stuff they used to do without even thinking. They used to be able to do it with their eyes closed and their hands tied behind their back. And now they're feeling like, Oh, I don't know. You know, I'm second guessing myself. You know, I don't know if I'll be at around that meeting or if I'll be able to last the whole day. And that can feel again, like the sandwich shifting beneath your feet.

Kellie [00:08:20] And overwhelming

Charlotte [00:08:20] Really overwhelming. And the second thing that we see as well as a big drop in confidence is a fear around sort of being swamped by polite inquiry. So almost like a wave of maybe your work colleagues or the people that you used to spend time with, almost like coming at you with doubtless good intent and genuine care and interest in how you are and what the last few months have been like for you, but it can feel incredibly scary because if you've been living a life where you haven't had any contact with any of those people and you've been kind of supported and felt loved and nurtured and scaffolded for the last few months or longer, and then you go back into this environment. in people's imaginations I think it can feel like literally an army of people walking towards them all going. Hi, how are you? You look great. Are you okay? We've been worried about you. It's so good you're back. And that can feel like a real pressure to respond to every one of those inquiries and also to respond positively. And you might not feel quite so positive, but opening up the can of worms of I'm not sure how I feel to be back or I'm actually feeling really exhausted and it's only 10.30 in the morning. You might not feel like you want to go there because that's a level of vulnerability that you perhaps haven't been practicing and you might not really want to establish right then and there.

Kellie [00:08:59] Is it normal to want to role play a little bit, you know, have the guard up and put your best foot forward and pretend like you're the old you? Because as we've discussed also in series one, that it's the next version of you, you can't go back. This is the next version of you and things have changed, whether you like it or not.

Charlotte [00:09:23] That's right. And a lot of people do a bit of go back in and put on my mask and be Charlotte 1.0. I'll be the version of me that I was before diagnosis and treatment. The problem is that isn't sustainable and the reality of what you've been through will inevitably catch up with you. And there's not many things I say with certainty, but I do say that with absolute certainty. But it can mean that, yes, we go back in because we feel like perhaps other people are expecting it. They're expecting me to look and sound and behave just like I used to. And that maybe there will be consequences if I don't. The reality, and we talked about FONEBO, fear of negative evaluation by others in the anxiety episode of this series. And this is one of those times when being real about the fact that if your boss isn't happy with you, if your bosses negatively judging you, there can be real implications for you. So if you come back and you aren't Charlotte 1.0 you might be a bit slower, you might be not be able to juggle as many cognitive balls as you used to. You might not last a whole day. You might not be able to do five days a week, 52 weeks a year, that there may be real implications. Now, again, I wish we lived in a world where that wasn't the case and that there was compassion and flexibility for everybody who's been through something like a cancer experience. But some workplaces aren't that flexible and sometimes there are real consequences if you aren't able to step it up the way that you used to. And that can bring on anxiety and that's reasonable, that's fair. And so that can lead to, again, wanting to put the mask on and be Charlotte 1.0. But the problem, as I said, is that inevitably, and it might take a while for that mask to get so heavy that you literally can't keep doing it, but it will catch up with you. And that can be a much tougher road to go.

Kellie [00:11:11] I think FONEBO is a really good way to describe it. But before anybody goes Googling FONEBO it's not there because it's a very special Dr Charlotte Tottman coined term!

Charlotte [00:11:27] Apparently it is!

Kellie [00:11:30] But it is that pressure, self-imposed or otherwise, can lead us to put on a mask that's not sustainable, as you said, and also set ourselves up for failure. So what are some strategies to set people up for success?

Charlotte [00:11:48] I think the first thing is to think about what we call a graduated return to work. Now, this is not possible in all work environments, but wherever it is possible, it's something that I strongly recommend. And if you are seeing your medical team at the time when you are going back to work, you can often get them to write a letter of support. I write lots of letters about graduated return to work and I think that GP's or oncologists or surgeons would similarly endorse that sort of approach. For big organisations, you know, big banks, you know, ASX listed companies they're familiar with, graduated returned to work. So it's not an unheralded strategy, it's pretty common in big organisations. But if you're working in a smaller organisation, there's no reason that you can't have a conversation about it. Now it doesn't mean that it's a guarantee that your employer or your manager will agree to it, but it's certainly worth the conversation. And a graduated return to work essentially looks like gradually returning to work over several weeks where you start off at a fraction of where you're going to end up. So if you work full time five days a week, let's say, and that's where you finish before cancer diagnosis, what I like to encourage is a graduated return to work over about eight weeks where in the first week or two you're only at work for a couple of half days and then a fortnight you step it up. So you might go from a couple of half days up to a couple of full days and then a couple of full days and a couple of half days and then eventually all full days. And what that does is it gives you the opportunity to increase your stamina and capacity, both physically, cognitively and emotionally. And it also sends a message to the organisation, to the people that you're working with, to your managers, that this is a recovery period, that you are in recovery, in rehabilitation. The message is in in the behaviour, if you like. So it doesn't then mean that you have to keep telling them every day, you know, reminder I'm still in recovery. It's like by the fact that you are only there for a portion of the time each week building up gradually over eight weeks, it sends them a message that things are not the way they used to be, but things are improving. Progress is being made. She is increasing her stamina and her capacity. But it's a slow process and it works really well. And what it does do is it sets the organisation and the person up for success because the risk is that if we go in too big too soon, exactly as you just described, it sets you up for messages of failure and disappointment and that can feel like the cancer experience has taken even more away from you. So it can feel like now I can't even do the thing I used to do before cancer. Whereas this gives you the opportunity to rebuild and to discover where perhaps there are things that are harder and easier. So, for example, after chemotherapy, it's not uncommon for people to have lasting fatigue and also to have cognitive deficits. Now, both of those things generally resolve with time, but sometimes it can be a long time and understanding that if you are going to take a bit longer to do something or that you can't multitask in your mind the way that you used to, you can adjust to that and you can find strategies that can help with that, but that also takes time and practice. And if you're going back into work full time 24/7 the way you used to, you aren't giving yourself the time to make those adjustments.

Kellie [00:15:23] There also needs to be some flexibility because whilst you might like to do three days, you might find that the fatigue sets in or that you might have overshot the mark. So when you're talking about a gradual return with flexibility.

Charlotte [00:15:38] Yeah, absolutely. And the idea is and certainly if I write a graduated return to work plan, one of the lines that I put in there is that this is always able to be renegotiated between the employer and the employee for mutual benefit. But yes, there does need to be recognition that all it is is a plan and plans can be modified.

Kellie [00:16:00] Sometimes these discussions aren't easy to have.

Charlotte [00:16:04] They really can be really hard to have. And a lot of these, just like in your personal life, depends on history. So if you've had a really good supportive working relationship with your working colleagues or your volunteering colleagues or your study colleagues, then you're going to feel probably fairly safe in going into a conversation about managing your post cancer treatment return to work. If you conversely have not had a supportive situation or if you've had bad experience previously with bullying or discrimination, then it's going to be really, really scary. And that's where I would say that first of all, you want to work out what it is you want, and so that can be through talking with another person, perhaps a trusted friend or colleague so that you can actually figure out what is it I'm asking for? What do I think is going to help me make the most successful return to what I used to do? Document it. So write it down briefly so bullet points so that it's nice and clear for you and for somebody else. Then think about arranging a meeting. And if you do have a meeting, you want to have a support person with you. So if there's an HR Department, you want to have the department involved. If there isn't an HR department, if it's a small organisation, you want to take a colleague or friend, and then that gives you the best chance, just like we were talking about in relationships with your medical team, there's a power differential in a workplace. And so being able to find strategies that are going to dilute that power differential can be really helpful. The other thing you can do is you can use technology, you can send emails in advance. So well before you want to return to work, you can start prepping for and start communicating with your employer or your manager, and you can get letters of support from people in your medical team to endorse whatever it is that you want to do. But I think that if we just allowed the discomfort of those conversations to mean that we avoid having them, then the risk is that we feel pressured to go back in and do things just as they were before and then find that it doesn't work and then feel frustrated because there could be a sense of like, I wonder what it would have been like if I had had the conversation.

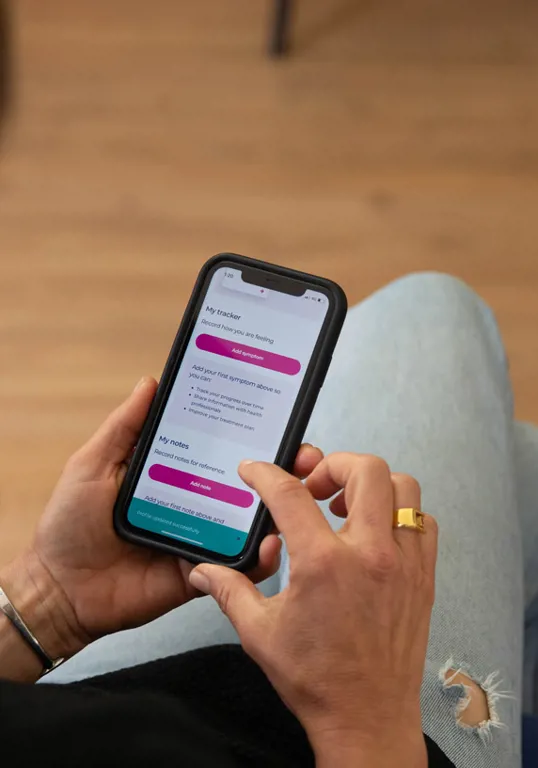

Ad [00:18:16] Looking for practical information to help you make decisions about your diagnosis whether DCIS, early or metastatic breast cancer. BCNA’s My Journey features articles, webcasts, videos and podcasts about breast cancer during treatment and beyond to help you, your friends and family as you progress through your journey. It also features a symptom tracker to help you manage the changing symptoms you may encounter during your own breast cancer experience. My Journey. Download the app or sign up online at my journey.org.au.

Kellie [00:18:50] You're talking about the return to work and there's that spotlight on someone who's returned after cancer treatment. How can you tackle that spotlight? I know you've got maybe some ideas on internal emails that can prepare colleagues for what you're happy to talk about, or what you’d rather not.

Charlotte [00:19:11] Yes, some clients have used this strategy quite effectively and it's again, not for everybody and it's not for every workplace. But if you've worked out that there are things that you do and don't want to discuss or that you would like to brief or have your colleagues know where things are at, if you literally disappeared sort of off the face of the earth for 12 months and you want to control the narrative, as it were, I've had some clients contact their manager and send them a paragraph or so, with a very simple update of what they've been through and where they're at, what they would like people to know, and ask their manager to distribute that information to a set number of colleagues using the internal email system. And it's like a briefing. And so that way, when they arrive at work on day one, post cancer treatment, there's already an awareness about why they were away, how they're doing, how many hours or what role they're going to have coming back to work. And so people are already briefed and in the loop, and that cuts down a lot of the pressure to respond to those inquiries. And it's a way of communicating the same information to a group of people at the same time so everybody gets the same information. There's no risk of misinterpretations or mixed messages. And again, it does work for some workplaces and not for others.

Kellie [00:20:32] Even with that possibly in play. How do you prepare your responses to those genuine lines of enquiry that can prompt a response that's possibly not quite considered from yourself and default to that “I'm great. I'm fine”.

Charlotte [00:20:52] Yeah, exactly. And so I think that's where I encourage people to consider the use of little scripts. So a script can be as short as a one liner or a two liner. It can be a bit longer. I wouldn't say it should probably be any longer than a sentence or two. And really it's something that is designed to be used on multiple occasions in many different environments where people might ask you, for example, you know how you're doing or make a comment about, you know, it's great to see you back. And so it might be something simple, like if someone says to me ‘you look amazing, it's so good to see you back’. If you want to make sure that you don't feel invalidated and you also want to communicate that yeah It's good that that the cancer thing is starting to get into the rear view mirror, but, you know, there's a long way to go. You can say something like ‘yes, I'm you know, delighted to be back. I'm going to be taking it easy and you probably won't see quite as much of me for the next few weeks. But it’s really good to see you too’. Something like that that references that you are happy to be there, but things are different. There are many, many versions of scripts and it is something like in session with clients we will quite often work one out on the whiteboard and they'll take a photograph and then practice it. And it's the sort of thing that once you get the language right, it will roll off your tongue quite easily and it doesn't matter at all if you use exactly the same script in the same environment. And even if other people hear you say precisely the same thing to Bob, as you said to Fred, because the message in the message is, I've thought about this, and I am prepared and I'm giving you the response that I want you to have. I'm in control. I'm doing this on my terms. And that's a nice feeling when you're going back into that environment that might feel a bit unfamiliar and a bit foreign.

Kellie [00:22:43] It's all well meaning, though. Is there any harm, even if it isn't quite thought through? Perhaps a nervous comment from co-workers like you said, ‘you look great. You'll be fine. You're so brave. You're an inspiration’. They’re well meaning. Do they do any harm?

Charlotte [00:23:04] Yeah. We call this toxic positivity. And look, sometimes it's not toxic, but like anything, if you have too much of it, it certainly can feel toxic. In the first series, I think I referenced this idea that we get as humans hung up on the interaction, which is the delivery. We get hung up on what they said and we don't always look behind to the intent. And so sometimes and this is hard to do, easy to say, but sometimes it can be helpful to just step back from the actual interaction and think about, okay, that was a bit clunky and clumsy. I wonder what they were meaning? If you think you can figure out and often it will be the case that they were meaning to say, essentially, we just really glad that you're okay, then maybe we can be a little bit generous of spirit and give them a bit of latitude about the clunkiness that they might have expressed it. Toxic positivity is not often done with any mal-intent. It's almost always with either no real intent or with genuine positive intent. People aren't meaning to be harmful or toxic or annoying. They usually have just not had the experience themselves and they're clumsy.

Kellie [00:24:17] You're saying it's similar in a community situation? Same, Same bit different. So with the carpools and the volunteering and so you you're wanting to get back into a bit of the life that you had before. Whether it be doing three days of the carpool.

Charlotte [00:24:35] Yeah. And it can be a bit tricky because the thing about environments like work and study and volunteering is there's usually a framework, there's rhythms and routines, there's schedules, and so therefore there can be an ability to set limits and boundaries of what you would like to do and are capable of doing. And you can be explicit about them. You can say, I'm going to come back to work and I'm going to start coming back to work two mornings a week. And it can be fairly clear and easy to follow. In more of the community type scenario it's harder, it's blurrier and it can be really hard to navigate that in a way that doesn't mean you fall back into doing everything that you used to do before diagnosis, but also doesn't mean that you don't do anything. And there can be, especially in parenthood generally, there can be quite a lot of pressure to be back being the parent, being the mother. And again, I mentioned mother guilt a number of times. We're very good at beating ourselves up about the burden that the cancer experience has placed on the family and almost wanting to compensate for that by getting back and doing as much as I used to, or horrifically even more.

Kellie [00:25:53] We've talked about the blurred lines of community. They become even murkier with the inner circle of family and dependents, whether it's elderly parents or children, other people that you support. How do you do a graduated return in reality?

Charlotte [00:26:12] Yeah, it's really hard to do it with your family. I mean, I think that a lot of it comes down to boundary setting and communication and we are going to do a whole episode in this series on boundary settings. So, you know, stay tuned. But I guess the first point is to again, accept rather than resist, the idea that things are different. So if we do tend to, as a lot of us, me included, post treatment is to go like, you know, I'm just going to get back to normal and do all the things I used to do. And if that's the place that our head is in, and that's a place of resistance because we are resisting the reality, that things have changed, then we're not going to talk to anybody about doing it different. We're not going to make plans to set a boundary or set some limits or increase our self-care. We're just going to plough on and the risk is that we then really set ourselves up for emotional, particularly emotional and physical crash further down the track. And we don't give our family the opportunity to be part of our adjustment. It's like we hold ourselves separate from them. And just like I said in an earlier episode, I think that means that we aren't giving them the chance to support us, and we also aren't giving any of us the chance to see that perhaps people are a little more flexible and resilient than we might assume. You know, that rigid mindset of like things have been this way forever, so we need to keep them this way forever. That's rules. And rules are tricky because as soon as you create a rule for yourself, you give yourself the opportunity to break it. And if you break the rule, then it's like good and bad. If I broken the rule, I'm a bad person. I'm a bad mother because I haven't done all of the things that I used to do for my kids. So developing that psychological flexibility and being able to go, you know what? If we need to do things a bit differently now post cancer, maybe for a couple of years, maybe forever, that's not a bad thing. It might be a scary thing because it's unfamiliar territory and that's why we don't want to go there. But and again, this sounds really naff, but it's giving your family the opportunity for personal growth.

Kellie [00:28:33] And you're right, that really does sound naff!

Charlotte [00:28:37] The truth of it is that testing that rule, testing that boundary and going, do you know what? Maybe I wonder if there is another way that we could do this. You know, I don't know if we need to just do it the way we always have. And you might not find that the first version of a new family model of changing who does the chores or changing what time you go to bed or who picks up the kids. It might not be the first model that you come up with that's the right one. But I really like flexibility and I really like the idea that we play with that in the post-treatment adjustment space. And we don't just accept or expect that the only way to do this and to navigate that space is to go back to how it was before because it doesn't work.

Kellie [00:29:22] It must be really normal, though, particularly in a family setting for people to want to reclaim their spot that they have, their relevance and their mattering and being needed. Everybody wants to be needed.

Charlotte [00:29:35] And I've had a lot of clients who have talked about, I'm reflecting on this, I think even possibly through treatment, the feeling of not being redundant and discovering that actually other people can do some of the stuff that they've always kind of felt was, you know, essentially their role, their space. They owned it. And again, this all falls under the heading of adjustment and it can feel quite invalidating as a human because you can sort of feel like, oh, I'm not needed any more. They don't I don't perhaps want may possibly somebody not only could they do what I was doing, but maybe they've would that could even do it better. Ouch for sure but again, with perspective and time reflection and maybe some discussion with a therapist, you can get to the point where that can actually be seen as a benefit in the short term. I get it. It hurts and it can feel like I don't matter or belong or I've lost my spot, my space, my identity. And it's like cancer’s taken away quite enough already thanks very much you don't need to take away that as well. But actually then being able to stand back from it and go, you know what, actually that's freed up some time and space in my life and put that into the snowglobe stuff. Maybe I can do something that has more purpose and meaning for me than maybe some of that stuff before that I was doing simply because no one else would.

Kellie [00:31:00] It's very normal for someone who's had to step back from their family and dependents to feel guilt that they've had to step back and therefore might feel like they've got to make up for the lost time.

Charlotte [00:31:14] Yeah, I think there can be a sense of like, I feel so bad about the burden that this has all placed on my family that I want it to be over as fast as possible, and I want my return to be seamless and 100% from the beginning and no sense of like I'm going to gradually, you know, get my mojo back. It's like, right, I'm back, you know, day one after radiation, game on. We are back to life as it was before cancer, and I have had plenty of clients with that aim and I have helped reset some of their expectations. It is really common and guilt plays a really big part in that and women are really good at guilt. Again, a lot of this stuff is about awareness and about understanding the short term feel good of, you know, I've gone back and replicated the week that was before diagnosis. But then think about, okay, what's that cost me? How do I feel? Do I feel like I did before cancer? I mean, most of us won't know the answer to that because none of us were thinking that a diagnosis was coming. But I think reflecting on is this really what I want to do? Or am I doing it because it's a should? A should is another word for a rule. And so if you feel like I'm doing stuff because I should do it, that is worthy of pause, that is worthy of thought and reflection. And sure, there will be a bunch of stuff that you probably do need to be doing, but there may well be some shoulds in there that could be addressed more flexibly and that you could think about, okay, I wonder if somebody else could do them. I wonder if maybe I could do them a bit differently and I wonder if maybe I could perhaps set the standard a bit lower. And we'll talk about that in boundary setting.

Kellie [00:32:53] That's one scenario. There could be another scenario a bit like the old snow globe that we've talked before where everything is thrown up in the air and your life lands down in a different space and all of a sudden you've seen that other people can step up and you're like, Well, hey, this, this is good. This is the way it's going to be now. So what happens when other people haven't caught on to that? So you've got this epiphany of I'm not going to cook three courses anymore and we're going to have takeaway twice a week. And if that is in line with your partner's values or those other changes, if you can agree otherwise, it could possibly cause a little bit of tension.

Charlotte [00:33:40] I was asked recently about how many people kind of having a have an epiphany and then act on it after cancer. And I think I have no data to back this up. But I think my impression from my work is that about a third of people have some sort of an epiphany where it's like, okay, I want to change my life and I want to do something really purposeful and meaningful now. I think a third of people probably have an epiphany and don't actually do it. And then I think that a third of people don't have an epiphany. And even within the people who don't have an epiphany, they feel like they should have one.

Kellie [00:34:11] Like ‘Where’s my epiphany?!’

Charlotte [00:34:13] Yeah and they feel a bit ripped off because it's kind of like, you know, well, at least I thought I was going to get that out of a cancer experience and then I don't even get that! So I guess probably what we saw out of that is that then possibly there are only about a third of people who actually do have an epiphany and go on to make the changes in their life to reflect that. And I'd say within that group there is probably a number of families and partners who are on board with that, who are like, yep, we see it. You know, Mum's talked us till we’re blue in the face. We understand you know, she wants to give back to the cancer community or she wants to build houses for refugees or she wants to save small animals or whatever. And I'm not trying to diss anybody doing those things because they're all good. I do my stuff because of my epiphany. I do this stuff because of my epiphany and my family supports me. So I know that that does happen where people have an epiphany and they communicate it. And that's probably the thing, is they communicate it, they share it, they educate people in their in their community, in their social support network about what's occurred to them, why it has purpose and meaning, what they're going to do differently. And I think with that information and understanding, they increase the chances of support if they don't, and they just get busy with their epiphany that's where things can get tricky because people around them can be busy thinking, you know, we're expecting Charlotte 1.0 to walk through the door and Charlotte, 2.0, walks in through the door and we're like, What? Hang on. What is going on here?

Kellie [00:35:44] So what you're saying is, whereA with you, you are able to give up that cooking that you used to do five days a week and it works because Rob's children were older and your husband stepped in. For someone that can't do that, there might be a smaller scale.

Charlotte [00:36:04] There might be a smaller scale. And we talked last time in series one about approximating and about finding ways to do things that you want to do in a way that's similar but might not achieve all of the aims. And so, yes, it might be that there are parts of your life that you want to change, and rather than bumping up against it and feeling frustration and going, right, well, that's the end of that idea and all I'm going to feel is frustrated and resentful because I want to change my life and the framework of my of my family or the structure of my life will not allow it. Rather than just stopping at that point, it's about being, again, psychological flexibility, being able to go, okay, I wonder if there's another way I can come at this, if there's another way that I can do the thing that fills up my cup that doesn't actually have to be the not doing the cooking or the thing that isn't going to work for the family. And again, like it's very individual and it can feel effortful to have to brainstorm and research and think about what that thing might be. And when things get hard, that's quite often when we don't do them, when we go, it's just too hard I don't know what would help me, you know, if I can't do A, then I'm not even going to bother to try and think of B and C but bothering can be really worthwhile.

Kellie [00:37:18] That would be a really interesting thought process for those who prior to their diagnosis were very active in maybe the tuckshop or giving time in a community hall or something like that. Deciding that's actually no longer possible or no longer brings you joy or is just too hard. What you're saying is it all needs a conversation so that it's about being transparent and being authentic about where you're at now.

Charlotte [00:37:50] Exactly. I mean, I read somewhere probably on Instagram because, hey, everything's on Instagram, that if you want something to change, it almost always requires a conversation. That's a very simple statement, but you know, it's incredibly accurate. Not much can change unless you live on a desert island by yourself. Not much can change in a way that works. So not much can change successfully without a conversation.

Kellie [00:38:15] But it can be awkward, can't it? Because you also as well as with those feelings of guilt in that you've stepped away from your family, there's perhaps a real feeling of needing to pay back or give back to those that have really stepped up for you. So the people that have stepped up for the school run, the people that have dropped off meals for you or taking your kids while you've gone and had treatment. It's there's almost a compulsion to overreach.

Charlotte [00:38:46] Yeah and to perhaps overcorrect. I think that again, we come back to the fact that cancer may be considered a relatively short-term interruption, but in fact it is not, and that cancer has a long tail. And that's the bit that most people don't know about. And that's the whole post treatment adjustment goes on for at least two years. I've been doing a lot of public speaking in the last few years, some of it to medical professionals. And I've got this terrific image that I show, which is like a treasure map, and it shows the point of diagnosis and then a couple of points where the hospital based treatment is an in a really long line and it says post treatment adjustment. And that's the longest part of the map, the long, long post treatment adjustment phase. And people who are medical professionals look at that diagram and you can see it's like, oh, I had no idea. The focus is so much on that front end. When you disappear and you're in treatment and you're not doing the school run and you are needing the lasagnas and all of that. And so there can be a sense of like, yes, when that's over that I'm going to I'm going to come back and I'm going to come back at least as good as I was, and possibly even bigger and better to show people that, you know, thank you, but to show people that I'm all good. And again, that almost always no, always does end badly. Not immediately because we can all do that for a little while. I did it for a few months, but it ultimately catches up with you.

Kellie [00:40:15] So it's walk, don't run. Thanks for joining us on this episode of Upfront. If you found it helpful please share it with someone you know. And don't forget that BCNA has many resources to assist you go to bcna.com.au. In the next episode of what you Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited, We talk about common behaviour changes after cancer treatment. I'm Kelly Curtain. It's good to be upfront with you.

Ad [00:40:45] Your first call after being diagnosed with breast cancer can be difficult. The BCNA Helpline can help ease your mind with a confidential phone and email service to people who understand what you're going through. BCNA’s experienced team will help with your questions and concerns and provide relevant resources and services. Make BCNA your first call on 1800 500 258 or email helpline@bcna.org.au. Coming up in episode six of Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Ulimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman, Hanging out with the bad boys: Helpful and not so helpful behaviour changes.

Charlotte [00:41:25] The other thing that's common in behaviour change is the role of obstacles. If an obstacle presents itself right when you're ready to make all these positive changes, it can derail the very good plan. And the thing that typically presents as an obstacle right after diagnosis, is treatment. So you might be already to like get your gym shoes on and eat less processed food and worry positively about your sleep more. And then along comes treatment almost, you know, within days. So your actual ability to be able to engage in those behaviour changes consistently from the outset is usually impeded by treatment. What we know about behaviour change is that it is sustainable in incremental change over time. So small change over time. and there's tons of research about the fact that behaviour change doesn't stick for a while and the hardest part is the beginning. So the first few days, the first two weeks are going to be the hardest and that's where you're going to have more self-doubt, more wobbles and probably more of the need for that self-compassion.

Ad [00:42:32] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Sussan. Our theme music is by the late Tara Simmons. Breast Cancer Network Australia acknowledges the traditional owners of the land and we pay our respects to the elders past, present and emerging. This episode is produced on Wurundjeri land of the Kulin Nation.

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=384&height=240&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

![[blank]](https://bcna-dxp.azureedge.net/media/en2fczb2/bcna_placeholder_bg.jpg?rxy=0.7593219354887106,0.2881619937694704&width=64&height=64&format=webp&quality=80&rnd=133546802863430000)

Listen on