Voiceover[00:00:08] BCNA’s Online Network is a friendly space where people affected by breast cancer connect and share their experiences in a safe online community of support and understanding. Read posts, write your own, ask a question, start a discussion and support others. You're always connected, which means you're never alone as our Online Network is available for you at every stage of your breast cancer journey, as well as your family, partner and friends. For more information, visit bcna.org.au/online network. Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman.

Kellie [00:00:57] Welcome back to Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with clinical psychologist Dr. Charlotte Tottman. This is episode two in our second series, which delves into the instant trust and faith you push into complete strangers at arguably one of the most fearful and uncertain times of your life. It's your medical team. These professionals will have your health as their number one priority but this unique relationship can also come with power imbalances that can get in the way of self-advocacy. So how do we manage this? What's reasonable? Are there rules of engagement? Charlotte we're going to find out.

Charlotte [00:01:38] We are. Just when you are probably at one of the most vulnerable times in your life, it's really necessary, helpful for you to stand up for yourself. What a combination.

Kellie [00:01:49] Absolutely. And a reminder that this episode of Upfront about Breast Cancer is an unscripted conversation, and it's not intended to replace medical advice nor represent the full spectrum of experience or clinical option. So please exercise self-care when listening as the content may be triggering or upsetting for some. Dr. Charlotte, the medical team, the relationship's instant and it's fast and it's furious and more often than not It's amazing.

Charlotte [00:02:18] It is. And I think I do want to make that point at the outset that we in Australia do have the happy experience of an excellent medical system generally. There are exceptions to that, but for most people, their medical team, their relationship with their medical team and broadly their treatment experience following cancer diagnosis is a good one. It's as positive as it can be. Now, today we're going to talk about, you know, when it's not going so well and how to help that and sometimes when to know when to cut loose.

Kellie [00:02:54] So they're bit like friends and family. You can pick your friends. You can't necessarily pick your family, but they're your family. And there's ways to make the best of it. Tell me more.

Charlotte [00:03:05] I find this topic really interesting because trust is a really important part of being a human and it's a really important part of relationships. And I quoted Brené Brown in the last episode and I'm going to do it again. For those of you who don't know who Brené Brown is, she's a professor of social work in the United States in her mid-fifties, incredibly talented, does a lot of research around big psychological constructs, including trust. And she uses this analogy about how typically and the reason it's interesting is it's not what happens in this instance with the medical team, but typically with trust we build trust gradually over time. And she uses the analogy of a marble jar where she talks about at the beginning of any new relationship. It's like you start with an empty jar, an empty glass jar, and every time one of you does something that the other person perceives as trustworthy. So you show up when you said you would show up, or you phoned them back when you said you would, or you invite them to do something that's, you know, important with you. It's like you put one marble in the glass jar and over time and often a long time, years, often your marble jar gets increasingly full of marbles. And those marbles represent the amount of trust in the relationship. So that's typically what happens in friendships, in intimate relationships. And it's so different to what happens in this context when you are diagnosed with cancer.

Kellie [00:04:36] Because you're expected to put all your marbles instantly in the jar for people who really are in charge of your life and who you’ve never met before! and definitely in a in a public health setting, you don't get a choice.

Charlotte [00:04:52] You don't get a choice and even, you know, in public or private, you often because you haven't been diagnosed with cancer before, most people have been diagnosed with cancer before. They haven't got a list in their wallet of like which breast surgeon I'd like to go to or which medical oncologist. I mean, even me and I work in this area and I have a lot of surgeons and oncologists who refer to me. I mean, it wasn't automatic. You know, I have access to probably more names than most people a nd there's still that sense of like, I'm diagnosed and within hours I am meeting the people who are going to have my body and my life and my future in their hands. And I don't really have time to even think about whether or not I'm going to trust them. You just have to. It's like a leap of faith. You just have to do it.

Kellie [00:05:46] And straight off the bat, I'm thinking there's a power imbalance, there's possibly a gender imbalance and these health professionals more often than not, this is their every day. They know so much that the knowledge imbalance is massive, too.

Charlotte [00:06:06] Absolutely. I mean, there's the whole kind of white coat syndrome. You know, they're sitting often behind a desk and all of this stuff does matter. You know, in psychology I don't sit across a desk from someone. I sit at sort of 90 degree angles on a piece of soft furnishing, you know, a couch or a comfortable chair. In a medical setting you're very often in a clinical room. You are on one side of a desk and the medical professionals on the other, they're usually wearing, you know, formal professional clothes, not often a white coat these days, but still, nevertheless, there's that sense of authority. And, you know, they'll be dressed professionally. As a patient you are often not in your work attire. You might be on diagnosis, but after that you'll often be going in in your more casual clothes. And if you're in treatment, you might even be in a hospital gown or something like your pyjamas. And I know it sounds a bit kind of unusual to, you know, focus on things like attire, but people take in information through their eyes. And so if I'm sitting there, you know, I kind of in a gown with my bum hanging out the back and I'm across the desk from a person in a you know, a tailored grey suit, I am going to feel vulnerable in addition to already feeling vulnerable because I've been diagnosed with cancer and I'm going through treatment. So it is an environment where under normal circumstances we might not feel like we are subject to imbalances, power differentials, that's what we call them, power differentials, differences in power. But you get into a medical environment in the context of a cancer diagnosis and you can really feel on the back foot.

Kellie [00:07:48] And that's scary.

Charlotte [00:07:50] It's really scary. And the system, the environment doesn't really work to make it any less scary. I mean, the focus is very much and rightfully so, on identifying what we need to do in terms of treatment and cracking on and getting on with it. It's not about spending a lot of time getting to know you, understanding who you are and what your history is. I mean, we do that sort of thing in psychology, but usually well down the track, you don't tend to do very much of that in a medical context. So you may well be sitting there feeling like, you know, I'm feeling vulnerable in all sorts of ways. And often these power differentials and how we might feel disempowered in the medical setting is not necessarily front of mind either. You know, you as the patient, you're probably very focussed on, you know, the dates of appointments, getting ready for things like surgery, chemo treatment, managing your life. You might feel that things are not quite the way you'd like them to be, but I think also we're really accepting of that because it's kind of like, Well, what's the alternative? You know? I mean, if I'm waiting to feel comfortable in this environment, that's probably not going to happen. And sometimes it's not until things get to a point where maybe, you know, a level of discomfort bubbles up into something that that gets in the way of making a decision you're happy with. So if you're being advised or guided in a way that doesn't feel like it's respecting who you are or taking your position into account, then maybe the discomfort that you might feel on a smaller level can bubble up into something much bigger and it can feel like, okay, maybe I need to do something about that now.

Kellie [00:09:36] Okay, so let's talk expectations then. What is reasonable and what isn't?

Charlotte [00:09:44] I was talking about this issue of working with your medical team and I guess figuring out where you sit in relation to your medical team when I was doing a BCNA forum a couple of years ago and in preparation I thought, Well, I wonder how many people are in a person's medical team? And I wrote them all down and to my absolute horror I discovered that you can have as many as 18 people or more in your medical team. That's an AFL team. That's a whole team on an AFL football ground and just one of you. So that's including people like your surgeon, your oncologist, your radiation oncologist, maybe your psychologist, your naturopath, your acupuncture therapist, your lymphedema physio specialist. I could go on and on. It's an interesting exercise for anyone listening they might want to write down who are all of the medical professionals, they're seeing. But if you think about that just from a numbers perspective, if there's only one of you and 18 or so other people that you're liaising with, figuring out what to expect from each of them can actually be really helpful because if you expect the same thing from all of them, you are inevitably going to be setting yourself up for disappointment.

Kellie [00:11:05] Okay. So with the expectations, what should be at the top of your list? I mean, some people don't have a good bedside manner but their track record in results speaks for itself

Charlotte [00:11:19]Yes, absolutely. So I think yes, working out what you want from each of the people in your team. So, for example, I think sometimes we get introduced quite early in the cancer experience to people like surgeons. And surgeons are often technically incredibly skilful, but interpersonally that's not always their strong suit. Now that's a broad generalisation and there are certainly surgeons out there who are, you know, fantastic with their bedside manner. But learning where you want to get things like your emotional support from can be really helpful. So if you feel like I need to feel like I matter and I really need to feel like someone cares about me, and if you don't feel like you're getting any of that from your surgeon or your oncologist, okay, I would say that's still a problem. But if you feel like they're the only person that you're looking to meet that need, then again, you might be setting yourself up for failure. So it's about recognising, okay, do I want to get my emotional needs met from my surgeon or do I want to get my surgical needs met from my surgeon? And I think when I say those words, probably most people can understand that the sensible answer is, Well, I want to get my surgical needs met. It's not always that simple, however, but that as a starting point is a good place.

Kellie [00:12:40] So if you don't feel like you matter and that could be a problem. So what you're saying is if you've got your team of 18, it's horses for courses, it's who can offer me the emotional support, the connection, the mattering, the time...

Charlotte [00:12:57] The eye contact, the skill, the accessibility. There's all sorts of ways that we feel like we matter. I mean, most medicos won't provide you with their mobile phone number, so you often will have to go through, you know, an admin person or department in order to get access to them. It's hard to sometimes even get an email address. And when people do have that accessibility, they really do feel like they matter. Now, I can't tell you to demand that. And even if you did, I can't tell you that it would work. But I think understanding what it is that you feel you want or that you're not getting and identifying that can first be helpful. And the second thing is, and this is really easy to say and much harder to do is to ask for it.

Kellie [00:13:48] Yeah, how could you do that?

Charlotte [00:13:50] Take away the mobile phone and the email is what you're asking for and maybe ask for something a little simpler. So it might be to ask for a little more time and it might be as much as 5 minutes. 5 minutes sounds like a short time, but actually, if you're sitting with someone, it's just you and that other someone 5 minutes can be quite a long time. It might be asking for some more eye contact. There can be a whole lot of historical factors that can influence our ability to be able to step up and speak for ourselves in the moment. So I don't want to imply that this stuff is easy or that it's the same for everyone. The first step, however, is identifying the thing that you're not getting that you would like, and then working on a way to communicate that to the other person. Now, sometimes it can be using your words, your language, and it can be sitting in front of the other person, so in this case your doctor, and saying, I'm really struggling with our relationship. I really didn't like our last appointment and I'm practising my self-advocacy skills. I love those words, practising my assertiveness, practising my self advocacy skills, because what that communicates to the other person is this is new territory for you, that you don't have practice at this and that you are declaring your vulnerability that usually, not always, that usually gets you a bit more compassionate result. It also is likely to tune them in to you and get them to pay attention.

Kellie [00:15:10] It's also a little bit less confrontational. It's like you're not giving me the time I need. So am I right in suggesting that if you're wanting some more time, demanding it at that point probably is not going to work with a busy person, that's schedule. But as you leave, you say, next time, could I arrange to have another 5 minutes.

Charlotte [00:15:29] And the other thing too is that I think most people listening, me included, has had those experiences where you go home after that you go, Damn, why didn't I say something then? You know, and you come up with the pithy kind of line after the fact, but you don't have the wherewithal in the moment to say the thing that you really wish you had. So sometimes what I've recommended to clients, too, is when they are seeing their surgeon or oncologist in relation so that perhaps they're only having a point. In relation to treatment. Sometimes if there is a particular issue that they want to try and address, they set up a separate appointment, particularly to address that issue and they let the admin person know this is not a treatment related appointment. This is an appointment that I might only need 15 minutes, but it's an appointment specifically to talk about my relationship with my medical team. And I've had a lot of clients do this with really good results. What they often find is that because the appointment is not tied to treatment, the doctor isn't looking at blood results or scan results. They've come to the appointment with a different head set and they usually briefed by their admin person that this appointment is unorthodox, unscheduled in terms of the treatment protocol. And so they come to it with a kind of I guess almost like a curious willingness to, you know, find out what's going on. And the thing that we that I like about it is that it confronts the issue head on. We were talking about anxiety in the last episode and the tendency when something is not going right and not feeling comfortable is to avoid. And that's where people sometimes might go I either won't talk about it and I'll just keep sucking it up and I've got months to go with, or possibly years of my life where I'm going to keep saying this person.

Kellie [00:17:17] And you don't want to annoy them.

Charlotte [00:17:17] And I don't annoy them because, you know, if I'm already feeling like maybe I don't matter if I annoy them, like, what does that look like? I get even perhaps less time or less eye contact. But the risk is that we don't give the other person the opportunity to improve the situation. Human beings are not mind readers. Be great if they were, but they're not. And if we don't actually let the other person know what we need and respectfully ask them for it. I mean, if they're not able to do it and if they say, look, you know, I'm giving you everything, giving you all the time I can, I'm giving you all of the mattering that I can, well alright, then asked and answered. But if you never ask, then the risk is that you always feel, you know, sort of aggrieved, possibly a bit resentful even, and unhappy in your what is already a really tough experience.

Kellie [00:18:12] There's no doubt about it that medical diagnosis, such as breast cancer, prompts a very emotional response all the way along it. Like you said, it makes you feel vulnerable. It's a life threatening illness. So it's very hard not to get emotional. How can we try and avoid making a choice based on an emotional response?

Charlotte [00:18:36] Yeah, I think that's a really good question. What I would say to that is that we want to tap into the fact that we've got two minds, we've got an emotional mind and we've got a wise mind. And I referenced that I think in series one. But it can be really helpful that if you're feeling an emotional response in the moment when you're perhaps sitting in front of your medical specialist, it can be helpful not to react in the moment to that and to sort of say to yourself, like, you know, mental note. And that's really hard to do when having an emotional response, but to go away and then with a pen and paper or a computer or a phone to actually note down what it is that was bothering you. Make a list, it might only be a short list, but to actually write it down and that makes sense of it. And it means that you are engaging your rational mind. And then if you act on that, you're much less likely to be having an emotional response. The other thing that happens in all of that is time. So it's much less likely to be an impulse, knee jerk reflex reaction. It's more likely to be a considered one. And that's where you can also include in that reflective process, whether my expectations are reasonable, am I expecting more than this person is reasonably going to be able to provide? Do I need to consider that my emotional reaction was perhaps amplified because of what was going on in the room? Because I got another shock or I thought I was going in for my last chemo and he told me that in fact, I've got some more. You know, there could be all sorts of reasons why the emotional response was as strong as it was, and that doesn't necessarily dictate that reacting to it in the moment is a good idea.

Kellie [00:20:16] And obviously, when you're receiving information like that, we hear it time and time again that you remember the first sentence and then don't remember anything after that because it becomes a jumble. And we always recommend that where possible, you take someone.

Charlotte [00:20:32] Exactly. And that's another thing that can help offset the power imbalances that we feel even when you go into a session with your medical specialist. It's not to say that they're trying to exert power over you, but there is power often in gender, in age. Sometimes they're older, sometimes they're younger. And that sounds weird. But if you're a woman who's maybe in their Late seventies and you go in and see somebody who's in their forties who is clearly, you know, at the top of their game, cutting edge, you know, got plenty of years on the clock left to live. That in itself can feel like a form of power if you take a person with you, the numbers are on your side. It can feel like that empowers you. It can give you a little sense of like, I'm not quite as vulnerable. I've got a little bit of extra steel with me. And that can mean that I'm perhaps a little more inclined to speak up when something does need to be said rather than not. So yeah, there's many reasons to take a person with you and it's not just about the two eyes and eyes are better than one. It's that just more bodies in the room on your team can mean that you're actually empowered.

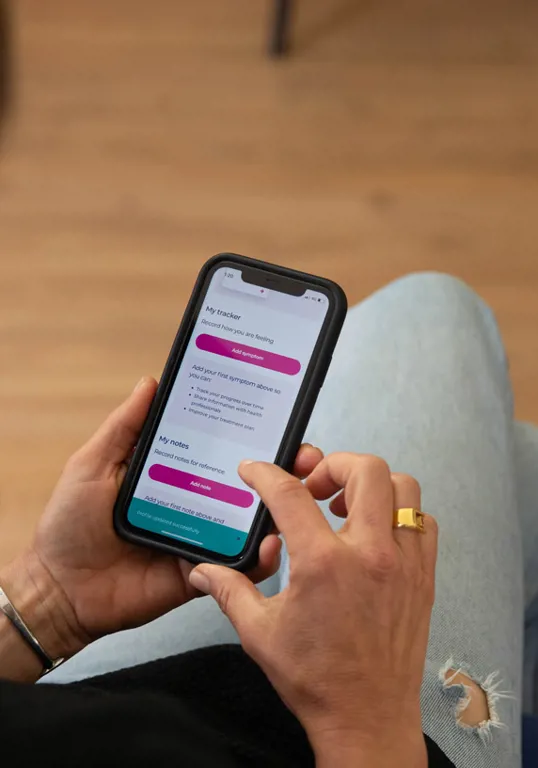

Ad [00:21:48] Looking for practical information to help you make decisions about your diagnosis, whether DCIS, early or metastatic breast cancer. BCNA’s My Journey features articles, webcasts, videos and podcasts about breast cancer during treatment and beyond to help you, your friends and family as you progress through your journey. It also features a symptom tracker to help you manage the changing symptoms you may encounter during your own breast cancer experience. My Journey. Download the app or sign up online at myjourney.org.au.

Kellie [00:22:26] Someone with metastatic breast cancer, that's a long game for a medical team. And that doesn't necessarily mean that the one team is always going to be your team.

Charlotte [00:22:36] That's right. And I certainly know of a lot of clients who have changed horses midstream, as we say, and not without careful consideration, because, again, it is there's that real sense of like, these are my people. And even if it's not perfect, sometimes the devil you know is better than the one that you don't. Not uncommon for people to consider second opinions. Partly that can be because there is, you know, perhaps genuine concern about whether we're doing all that we could or that the treatment protocol we've selected is the right one for now. And sometimes it's because the fit just doesn't feel right. And I talk about it in all relationships, regardless of whether it's like a marriage or a friendship or your medical team as there's this thing called goodness of fit. And goodness of fit is like when you put a key in a lock, it slides in smoothly and it works the lock nicely. When you don't have goodness of fit, everything feels just a little bit off. And in those types of relationships where things just don't feel, they don't necessarily feel catastrophically bad, but they just don't feel like things are gliding smoothly, that's where we're less likely to disclose. We're less likely to report side effects if we feel like somebody is not really giving us the time or the attention, or if we feel a little bit like I'm the slightly emotional female, then we can feel like I won't bother them with my side effects, I won't report them because I don't want to be seen as whiny. And so the issue of goodness of fit is a real one. And I do encourage people to reflect on their relationship with the medical team because it can have real consequences for your health. It's not just about whether it feels nice. It's much more than that. As you said, if you're living with metastatic disease, these people are going to be in your life for the rest of your life. You are going to do better in every way, physically, medically, psychologically, if you establish that goodness of fit. But just like most of us, take a few relationships to find a life partner, if in fact we do, it can take a few tries to find the right fit for your medical team. And that doesn't mean that you're a difficult person or that they're a bad person. It just means that this stuff matters and it's important to get it right.

Kellie [00:25:04] So it really is about taking back your power and that even though you're thrown together very quickly with a medical team once you are diagnosed, that if it doesn't work, sometimes your gut tells you this just isn't working. But it's really about stepping back, unpacking it to see perhaps why in a rational moment, going back possibly with a list and a person to say I've got some concerns here but if they're if they're still there for you, then it's worth considering.

Charlotte [00:25:37] Absolutely. And just as I was saying, I've had people who've changed horses midstream. I've certainly had plenty of people who've been able to work on their relationship with their specialist and get it to a place where they are more comfortable and they have taken back their power and advocated for themselves, and that's worked really well for them. And so it definitely doesn't have to be that you need to move away from your specialist. It can be that like any relationship, you can work on it and improve it over time.

Kellie [00:26:10] Okay, so you mentioned second opinion. Now, in an ideal world, everybody's friends and no one's going to be upset, but I would imagine that even though it's very common, does a medical professional know if you've gone and sought a second opinion?

Charlotte [00:26:32] Sometimes. Sometimes they even suggest go get a second opinion if they're if they're concerned that you're concerned. Sometimes it's a good double check for them as well. Yeah. Look, I've had plenty of clients say to me, well if I'm going to get a second opinion will I just kind of do it on the quiet or will I disclose? And obviously the disclose conversation potentially would be quite uncomfortable. You probably know from series one that a couple of my watchwords are transparency and authenticity. And so, you know, my stock standard advice is if you can bear it, I think it's better to be transparent upfront. And the reason, particularly in this context, is that if you go and get a second opinion and you go in and say my doctor has done ABC and then the second opinion doctor says, well, you know, I think that's pretty good but I wonder if they've considered, you know, J and M and you then go, Oh God, I really want to consider J and M but I haven't told my first doctor that I was coming to see this guy. So now I've got to go back after the fact and say I did go and get a second opinion. That's often a harder conversation than telling them you’re going to get a second opinion.

Kellie [00:27:51] Do you actually, though? Can’t you just get his people to ring their people?

Charlotte [00:27:55] Not easily. I don't know if there are guidelines in the medical system around second opinions, but generally speaking, it's like the patient kind of has to handle the information and what to do with it. It's unlikely, perhaps unless the two specialists worked in the same practice and happened to be well known to one another where they might kind of do a bit of a corridor ‘So, you know, we're working on blah, blah, blah’. I think mostly it's like, Right, well, I've handed you the second opinion. Now it's up to you to decide what to do with it. So if you haven't already, let your medico know that you were going to do that, going back kind of afterwards it's kind of like saying, So I didn't trust you and I'm back to tell you why. Which I think is a bit harder. Neither of these conversations are easy, But I think maybe in advance of saying, look, I've still got some concerns and, you know, my friend or my radiation oncologist has recommended that I go and perhaps have a chat to this person. I think that's transparent and authentic. And most doctor who have the well-being of their patients in mind actually aren't too bothered by that because what they want is for the best outcome. And sure, there are egos, nowhere more so than probably in the medical community. But I think that on balance, you know, the surgeons and oncologists I know are good people, they wouldn't be bothered by that sort of stuff. Not enough to matter, you know, maybe a little bit of a bruised ego, but not enough to matter.

Kellie [00:29:29] So that's second opinions. Let's talk about sometimes when it might be starting off Okay. Then something happens that makes you feel invalidated or uncomfortable and all of a sudden it was right and now it's not.

Charlotte [00:29:44] Yeah, and we call that a relationship fracture. And that definitely can and does happen. And look, it's not just in a cancer context and not just with medicos. It can happen anywhere. But I think it is about then recognising that's likely to produce feelings of betrayal and anger and that they are legitimate feelings and that feeling them and thinking them is generally not a problem. You just want to be mindful about what you might do. And that's where anger and angry behaviour can get us into trouble. But again, it's about, you know, sort of like pausing, reflecting and thinking carefully about what the right action might be. And for a lot of people in a situation where there's a relationship fracture, it is about then going on to find someone else to work with them to, to manage their medical health. But of course, if you've had and I think most people who've if they've been in an intimate relationship where there's been a betrayal or a fracture, trying to go into the next relationship with confidence and feeling like I can trust the next person is really challenging off the back of a recent betrayal. So sometimes it's, you know, necessary or helpful to declare that to the next person that kind of going to work with or you're going to choose to be in your medical team. And you can do that respectfully and discreetly. But, you know, you can say that we had a relationship fracture and I am still coming off the back of that. And so it's going to take me a little while to build up my trust. You know, the marbles, when you have a relationship fracture, it's not like when we talk about that marble jar full of marbles. It's not like you take out a few marbles. It's like someone tips the whole jar upside down and you go back to an empty marble jar and you've got to start from the beginning. And if you're halfway through a cancer treatment, if you're living with metastatic disease, starting to rebuild or build a new relationship with someone is hard anyway, even if it's not off the back of a betrayal or a fracture.

Kellie [00:31:46] It's that FONEBO again.

Charlotte [00:31:48] Yeah. Some of it's about how is this person going to relate to me? How are they going to judge me? And that's really relevant in terms of, I guess, the feeling that some of us have, certainly some of my clients have had where they've had worry about how they might be judged by their medical team, perhaps for their lifestyle choices or even for who they are as a person. If they've had experiences, say, with mental health or substance abuse, gender identity issues, even things like if they've got a history as a smoker, they might feel like they're going to be judged negatively. And that can sit in the relationship often unspoken and make it feel clunky. And it may be that the medico is not even aware of any of those things, but the perception or the worry that the patient may be judged for those can sit really unhelpfully between you and your medical professional.

Kellie [00:32:55] So what would you suggest to someone who does have a genuine fear of disclosure for fear of judgement, whether that be they're a smoker or they drink too much? And classically, whenever we fill out a form, it says, how many cigarettes do you have a day or how many drinks do you have a week? I think there's a lot of research to suggest that most people never fully disclose. So when is it okay to hold back? What about the LGBTQIA+ community.

Charlotte [00:33:27] I think it's so individual and it is very much a judgement call. And I think that again, it comes back to, you know, self awareness and reflecting on whether you think that maybe that uncomfortable feeling that you might not have really worked out what it is when you when you spend time with your medical professional working out, whether that's affecting your behaviour, if it's affecting how much you're disclosing, how much you're interacting with your medical professional, then there's a pretty strong argument to get it out on the table. Now, again, just like I said at the beginning of the episode, that's really easy for me to say. It's so much harder to do in the moment, and particularly if you had previous experience of being discriminated against or marginalised or judged, it can feel like, you know, exposing yourself in a very unsafe way. Sometimes it can help to have someone with you to do it. Sometimes you can do it in writing. So sometimes it's about you can literally write a note or an email. You can slideit across the table. That way you don't actually have to have the discomfort of voicing the words. But again, finding a way to let the other person know. It is confronting the fear. But I'm not going to be naive about this. You know, there is no guarantee that 100% of the time that that will go well. There is the chance that you will experience some sort of uncomfortable response. As awful as that sounds. I still think that's better to know that than to sit with the uncertainty of what you might be dealing with. Because if you confirm your fear, if in fact there is a negative judgement there, then that person is not your person and it's time to get a new person.

Kellie [00:35:23] So Self-Advocacy is super important no matter where you are or who you are. You have to feel like you matter. What about when there's not a whole lot of options? For example, if you're in a rural and remote area or in the public system where you don't feel like the balance of option is in your favour.

Charlotte [00:35:44] Absolutely. It's like the mattering thing is already a problem, Just because of the system or the environment that you're operating in. There's a power imbalance even before you get in front of a medical professional, It might be that you're you have to travel a long way, It might be that there's just not the availability, So there's longer waits. It might be that if you're in the public system, a lot of people would relate to the fact that you just wouldn't be seeing the same people in your team. And that's really hard. And it's really hard to stand up for yourself when you probably then have to stand up for yourself over and over and over again. And if you're already feeling vulnerable and like maybe you don't matter as much as you should, then that need to repeat your diagnosis, your treatment protocol, your particular situation where you live, your background, whatever, that can feel incredibly invalidating and isolating and it can feel exhausting and people can then give up because it's like, you know, like, I'm not going to keep doing this. Every time I come into the hospital, I'm going to have to retell my story and re-educate the next intern. And the curious thing about the public system is the better you're doing, the more likely it is that you'll see different people. If you're really interesting and really sick, you will see the consultant, you will see the guy at the top of the tree because you are either in jeopardy or your case is so interesting that they kind of like need to be involved to work out what they're going to do. If you are doing well, you're going to see more of the rookies. And you're going to see more different people week to week, month to month.

Kellie [00:37:35] And in our previous episode, we were talking about if you're interesting, meaning if you have a rare cancer. Or less than the more common presentations.

Charlotte [00:37:45] Yeah then you're going to be seen by the more senior which it's perverse because on the one hand it can feel sort of reassuring that I'm getting to see maybe the top guy and maybe I'm getting to see them a bit more often so I can develop a bit of a relationship and a rapport. But the flipside is that that may only be because your situation is more serious than other people. So it's kind of like, you know, be careful what you wish for in the public setting. It's really hard to manage a fluid medical team where you go in and today you're seeing, you know, Dr Sally and tomorrow you're saseeing Dr. Bob and next week you're seeing Dr. Fred. But the flipside, which is the only way to perhaps see Dr. John, every single time is if things are really serious.

Kellie [00:38:36] Okay. So being just aware of that is. Is that helpful?

Charlotte [00:38:41] I think it is. I think like some of the stuff I sort of intellectually, I know it and I feel it. But when I prepare for, you know, some of the stuff I do with BCNA and public speaking or even things like the podcast, it makes me go back and actually, you know, pull apart things like, well, what is it like if you're in the public system? and what is it like if you're in the private system? So awareness can be really helpful because it makes you make sense of things. It gives you an explanation for why things are the way they are and human beings like explanations. It gives us a way of feeling more at peace with things we can, I think I've said this before, put it in a box and put the lid on the box and put the box away. If you're sitting with like, I just don't understand why it is that every time I come into the hospital, I'm dealing with a different doctor. And if you can't figure out the reason for that it can leave you feeling frustrated. Whereas making sense of it, you can kind of go, okay, I don't like it, but I understand there's a reason for it.

Kellie [00:39:35] Can you still self advocate in the public system? Is there an artful way to do it?

Charlotte [00:39:44] I'd love to say yes, but I'm not going to say a categorical no. I think there is, But I think it is about understanding. It's a tougher road. And that maybe one of the things to think about is to be selective about when you do. Because if you kind of go, okay, every single time I have to go into a medical setting, I have to be ready to do hard core self-advocacy that may feel overwhelming and exhausting. it comes back to those expectations and what's really important, like going what's really important to me today is it really important that I do get to see the consultant who I have only met once and I've been in treatment for six months and I sort of recognise that my that my cancer is fairly, you know, middle of the road garden variety, but I'm still feeling like I need reassurance or oversight from the chief as opposed to wanting something or demanding something, you know, every single time. So I think being selective is important.

Kellie [00:40:46] And just finally, you mentioned exhaustion, like repeating the story, feeling like you don't matter. What is the impact of being exhausted all the time on our mental health?

Charlotte [00:40:59] It makes us more vulnerable and it decreases coping with everything. So if you're already feeling exhausted by not getting what you need from your medical team and repeatedly trying to advocate and either being successful but having to do it again to get the same result or having to do it over and over again to get the result that you need, then everything else in your life will probably suffer too. So you just feel like anything where if you're carrying a bag of rocks on your back and you're having to carry it for a long time, the weight of that bag feels heavier over time. So exhaustion affects our ability to cope with treatment, to manage side effects, to navigate relationships, to keep the few balls in the air that we might have decided we want to keep juggling through Treatment is going to make all of those things harder. The other thing that it probably does too, is it makes us more vulnerable to being emotional. And that's important because I mean, it's important anyway, because most of us like to feel a sense of control. Like, feel like we've kind of got our act together, as it were. Most of the time. The other thing is that if we're very emotional in front of our medical team, that can have flow on effects as well. Medical specialists, in my experience, don't really like emotion in the room. They can tolerate a little bit of it, but that's not kind of their bag. That's my bag. That's what I do. Yeah. I buy tissues in bulk. Everybody cries in my consulting room. It's just what we do. Conversely, when people get emotional with their medical specialists, that's often when I get referrals because the medical specialists get bothered by the by the emotion in the room. And sometimes that's legit. Sometimes the person really does need legitimately a psychological referral. Sometimes it's reflecting the specialist discomfort with the level of emotion in the room. But if you're feeling exhausted and more prone to being emotional, then it's more likely to leak out. And it might leak out in environments like the treatment room or the clinical room with your medical professional. And that can be, and I wish we lived in a different world, but that can be tricky because that can lead to judgements and assumptions again about perhaps being, you know, overly emotional, unnecessarily upset, which again, can leave people feeling very emotionally isolated.

Kellie [00:43:31] So it's important to matter. You've got to find the right people who can help you with their skill set.

Charlotte [00:43:38] Yeah, it's important to, I guess, work out who you want to meet each individual need.

Kellie [00:43:44] Fascinating stuff. Charlotte, Lots to think about. If you found this episode helpful, please share it with someone you know that might also find it interesting. And we really appreciate your feedback. So if you'd like to leave us a rating and a review, that will be great in our next episode of What You Don't Know Until You Do Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte, we're going to talk causal beliefs. In other words, your theories on what you think caused your cancer. Was it stress? Was it an event? Was it your lifestyle? Everyone has a theory, Charlotte. Do they?

Charlotte [00:44:19] Everyone does have a theory. And you might be surprised to find out what the most common one is.

Kellie [00:44:24] I'm sure we will be surprised. So until then, thanks for listening. I'm Kelly Curtain. It's good to be upfront with you.

Ad [00:44:35] Your first call after being diagnosed with breast cancer can be difficult. BCNA’s Helpline can help ease your mind with a confidential phone and email service to people who understand what you're going through. BCNA’s experienced team will help with your questions and concerns and provide relevant resources and services. Make BCNA your first call on 1800 500 258 or email helpline@bcna.org.au. Coming up in episode three of Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. Sugar, stress and, Misdemeanours: Causal beliefs.

Charlotte [00:45:16] Stress is a part of life. Life is stressful. It just is. And even if you arrive at a moment and it really would only be a moment when you could honestly say, and I'm not sure I've ever had one of these where you could honestly say, Oh, I'm there now, I'm in that place. I've got no stress that will only last for probably minutes, 2 hours, and then something will happen in a quest to have less stress. Often the rigidity around that in fact creates more stress. So often our behaviour ends up getting us more of what we don't want. So I get caught in this loop where I'm so scared about the thing I think cause my cancer that my main reason for being now my mission on earth is to keep that thing away from me out of my life. But that takes so much emotional and physical energy that that causes stress. And so then I'm caught in this kind of vicious cycle.

Ad [00:46:14] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Sussan. Our theme music is by the late Tara Simmons. Breast Cancer Network Australia acknowledges the traditional owners of the land and we pay our respects to the elders past, present and emerging. This episode is produced on Wurundjeri land of the Kulin Nation.

Listen on