Voiceover [00:00:08] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Breast Cancer Network Australia. Your first call after being diagnosed with breast cancer can be difficult. BCNA’s Helpline can help ease your mind with a confidential phone and email service to people who understand what you're going through. BCNA’s experienced team will help with your questions and concerns and provide relevant resources and services. Make BCNA your first call on 1800 500 258 or email helpline@bcna.org.au. Welcome to Upfront About Breast Cancer - What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman.

Kellie [00:00:56] Hello and thanks for joining us in episode one of our second series with clinical psychologist Dr. Charlotte Tottman, where we're going to be upfront about breast cancer and anxiety. Welcome back.

Charlotte [00:01:08] Good to be here.

Kellie [00:01:11] So there's many different types of anxiety in a cancer context. From diagnosis shock, to sexuality and intimacy, to anxiety, and perceptions of what others think. And who knew, not all anxiety is bad. Charlotte, who specialises in cancer-related distress, is going to tell us why but before she does a reminder that this episode of Upfront About Breast Cancer is an unscripted conversation and the topics we're going to discuss are not intended to replace medical advice, nor represent the full spectrum of experience or clinical options, so please exercise self-care when listening as the content may be triggering or upsetting for some. Dr. Charlotte, anxiety is broad. You're going to take us through a mixed dozen.

Charlotte [00:01:58] I certainly am. When I was preparing for this episode and I started writing down all the different types of anxiety that I see in my clinical work, I'd never actually counted them before, and it was a little shocking to find that the number was 12, and truthfully, it could even be more than 12. But I know it's at least 12, and we can't talk about all of those today because truthfully, we could spend this whole series just doing all the different types of anxiety. Some of them we covered in the first series. So, things like fear of recurrence and we did do quite a lot on sexual and intimate intimacy, and we talked about scan anxiety and review anxiety. So, we're not going to talk in detail about all of them, but we are about some of them for sure.

Kellie [00:02:43] So anxiety, how does that differ from depression?

Charlotte [00:02:49] Very loosely. Anxiety is about the future and similarly very loosely depression is about the past. So depression is tending to ruminate, go over and over things that have happened, wishing that was different. Whereas anxiety is commonly worry about things that haven't happened yet, and it might be things that that haven't happened, you know, not for ten years or it might be things that haven't happened yet, as in five minutes time. So it's just about the future. And of course, when you think about a cancer diagnosis, the first thing that most of us start to think about is what does this mean for my future? For the future of my family? For my own future in terms of health and wellbeing and perhaps even quality and quantity of life? So, it's a really normal common response to a cancer diagnosis.

Kellie [00:03:33] And is it always in your mind, can it be physical?

Charlotte [00:03:37] The thing that separates anxiety from a lot of other psychological responses is a bunch of physiological symptoms. And again, I think we touched on these in the first series, but it definitely bears repeating because sometimes we confuse anxiety, physiological symptoms, with other things. So for example, really common to feel a bit sick in the tummy, to feel that your heart rate goes up, maybe you get a bit hot and sweaty, you might even get, like, pins and needles around your mouth and you might feel like it's hard to get your breath. There are a bunch of others, but essentially what it means is there are physiological symptoms and most of us get some of those. And that's where sometimes it can be helpful if you're feeling a bit off, feeling a bit funny in the tummy, or feeling like it's hard to get your breath. It might be because you're having an anxiety response, and one of the ways to settle that down is to think about like, well, reflect on what's going on, what's maybe triggered my anxiety. And there are things that you can do in the moment to settle down some of those physiological responses like grounding activities, but it is really helpful to actually think about, you know, why might I be feeling anxious and what can I do about that?

Kellie [00:04:45] For example, in the lead up to a scan or the latest results, I would imagine be quite typical to have some sort of anxiety feeling.

Charlotte [00:04:53] Really, really common. In fact, I don't think I've ever had a client who doesn't experience their anxiety spiking in usually the two weeks before a test and then waiting for results is a particularly heightened time of anxiety. And the best thing you can do is get your scan and blood tests as close to your results appointment as you can, because there's nothing much else that helps bring that anxiety down other than the results, because the results are certainty. And that's essentially what we are often responding to with anxiety is a sense of uncertainty. Human beings don't like uncertainty or unpredictability, and anxiety rises in relation to the unknown, the uncertain and the unfamiliar. And you get all of those when you're dealing with not just the diagnosis, but with the treatment of cancer or the ongoing reality of living with cancer, for example, in living with metastatic disease where you don't know what your life holds for you.

Kellie [00:05:51] Could it be that some cancer treatments can cause physical symptoms that are similar to an anxiety response?

Charlotte [00:05:59] Yes. I mean, for example, nausea is a really common side effect of many cancer treatments, particularly chemotherapy. And nausea is a very common physiological symptom of anxiety. And so sometimes it's hard to distinguish whether you're experiencing one or the other. And, you know, it's not uncommon at all for it to be both at the same time. And sometimes when we experience a physiological symptom of anxiety, if we misinterpret it, we might think that there's something else medically wrong. And that, of course, makes the anxiety only go higher. So, I have a little diagram which I often send to people, which is like just a stick figure of a person. And around the stick figure, it's got all the different physiological symptoms listed. And sometimes I give it to clients and they take a photograph and leave it in their phone because when they notice the physiological symptoms, it can be helpful to just reflect on them and even look at the little diagram and go, “Oh yeah, okay, I do feel a bit light-headed and dizzy, or I do feel like my heart rate is up and I feel nauseous. Ah, okay. It might be anxiety, it might not be something sinister medically going on”. Now, if that stuff is happening a lot, then you do need to talk to your medical team about it. Because even in the event that it is anxiety and not something medical, there are things that we can do about that.

Kellie [00:07:20] Is all anxiety bad?

Charlotte [00:07:23] No. In fact, anxiety's normal. It's your internal burglar alarm and it's got a really bad reputation. You know, we talk about anxiety and depression almost in hushed tones as if there's something that there is that sort of stigma about and that's not right. We don't want to turn off people's anxiety system, but what we do want is for it to operate in what we call the normal range. There's no one normal way of having anxiety. It's like when people say to me, what's normal? And I say, it's not a setting on a dryer, you know, like it's there isn't a way to be normal with anxiety, but there is a normal range. And the way to know if you're operating outside the normal range is when your anxiety is bleeding out into other areas of your life and causing a problem. So, if you've got a fear of spiders and the way that impacts you is that you find it difficult to be alone in a room with a spider. I'm not that bothered about that. You know, we can manage that. It's not bleeding out into other areas of your life. But if your fear of spiders is at a level where it's impacting things that you would otherwise do and enjoy, like for instance, going camping with your family and your kids, or if your anxiety about your spiders is starting to bleed out in a way that makes your children also feel anxious about spiders, then that's potentially at a level where we would want to do something about it.

Kellie [00:08:43] Okay, so as you mentioned, there's so many types of anxiety. We're going to have a look at the mixed dozen. So, shall we start with diagnosis shock and anxiety in relation to that?

Charlotte [00:08:56] Well, I thought I might just, so that people kind of know what we're talking about with the mixed dozen. I thought I might very quickly just kind of list them that way people can understand, you know, what on earth are you talking about because who knew there could be so many different types of anxiety in relation to cancer? So yeah, first is diagnosis shock, and we did a whole episode on that in the first series, and essentially that's around the idea that you have a brain blast when you're when you're diagnosed and it takes quite a while for that to settle down. Fear of recurrence and fear of disease progression, which are similar but different. And I'll talk about how. Scan anxiety or review anxiety that we just touched on. New treatment anxiety, which is about every time you start a new treatment, whether it's surgery, chemo, radiation, immunotherapy, hormone treatment, that every time you start one, you often experience a spike in anxiety. Anxiety about the impact on family, wanting to keep things as normal as possible. Sexuality and intimacy issues, which is essentially anxiety about rejection. Fears about re partnering and the future and the family. So, you know, will my future be what I always thought it would be? Anxiety about coping post cancer, about going back to work or caring responsibilities or studying. Will I be able to manage? Anxiety about being an outlier. I'll explain what that means in a minute. And for FONEBO, which is a really cool shorthand for fear of negative evaluation by others, which essentially means fear of being judged negatively by others, and a very specific version of that which is around body image. So, they're the 12 and we're going to talk about some of them.

Kellie [00:10:38] Let's do that then. So diagnosis shock, as you said, we touched on this in series one, in episode one. What have you got to tell us that can enlighten us a bit more?

Charlotte [00:10:51] Nothing really. That’s good, isn’t it? No, essentially, I think the conclusion that we came to last time was that the thing that separates diagnosis shock as an anxiety experience from pretty much all other anxiety in a cancer context, is that because you don't know the diagnosis is coming, it's very hard to get out in front of it. With a lot of the other types of anxiety, there is the opportunity to, kind of, engage in strategies so that you can mitigate the risk and mitigate the impact. But with diagnosis shock, it really is more about understanding what happened and making sense of it after the fact.

Kellie [00:11:32] So really, it's a bit of a rearview and it’s that fight or flight.

Charlotte [00:11:37] Yeah, exactly. And I think I think it can be helpful, particularly if you do then go on to deal with a metastatic disease situation where you kind of have more versions of a diagnosis experience. And if you can take away some learning, and again, you can't see the next part of your metastatic diagnosis before it happens, but I think you can kind of perhaps be not quite, and I say this I'm going to completely deny what I'm saying, because this is one of the points that we do talk about a lot in the living with metastatic disease episode is that the learning doesn't really apply. If somebody pulls a gun on you, it doesn't make it easier the second time. It just doesn't. I think maybe your recovery is a little quicker and we'll talk about that. So maybe you are able to recalibrate and get your equilibrium back, perhaps a fraction faster with each repetition, but I don't think that there's much else that's able to be improved.

Kellie [00:12:46] So as you were saying, with recurrence or progression.

Charlotte [00:12:50] Yeah, I was thinking about this last night because I was trying to think of a really clear way to distinguish between fear of recurrence and fear of disease progression. So fear of recurrence is typically experienced by people who have gone through an early breast cancer diagnosis and essentially for the rest of their lives, and this is me, essentially for the rest of their lives, there's a part of them that fears recurrence. And so that isn't if the cancer comes back situation. The difference with fear of disease progression is that this is typically experienced by people living with metastatic disease, which means the cancer has already spread. They've already, in most cases, had a recurrence unless they were diagnosed as metastatic from the very beginning. But a lot of them have already had a recurrence and so their experience in terms of anxiety is not an ‘if’ situation, it's a ‘when’ and ‘how’. So, they're not worried about if the cancer progresses, because that's unfortunately part of what they know is going to happen, because they are living with a disease that is now treatable but not curable. What they are often concerned about, very reasonably, is when is the next progression going to happen and how is it going to happen and how is it going to affect their life. So, I think it's really common maybe with medical professionals and possibly even with mental health professionals to kind of bundle the two in together and go, you know, disease progression and fear of recurrence are kind of the same. They're definitely in the same family, but they're not the same thing because they have really different meanings. And I think it is important to make that distinction respectfully, particularly for the people who are living with metastatic disease.

Kellie [00:14:35] And of course, these people would be triggered whether you're metastatic or fear of recurrence when we hear of a friend, of a friend or a relative or someone like Olivia Newton-John, who was living with metastatic for a very long time and we knew that it was not curable so that it was coming but still, when she died, it would have been extremely upsetting and confronting for a lot of people.

Charlotte [00:15:07] It was a huge trigger and even now, you know, many months later, I still have clients referencing that as a trigger for either their fear of recurrence or their fear of disease progression because it affected people with both early breast cancer and metastatic disease. And it was a huge trigger. And I think when I've reflected on how big a trigger that was, and I know for myself the morning that it happened, I woke up and we've got a TV in our bedroom, you know, much against all psychological advice, and my eyes opened. Rob had already turned the TV on and my eyes opened and Olivia Newton-John's face was on the screen and it said beneath her face, Olivia Newton-John dead at 73 or 74, and it took my breath away. My eyes filled up with tears and I thought, like, that's a strong reaction. I was sort of like at the same time as being quite distressed, I was also quite surprised. And then I went to work and there was a lot of distress in the room that day and then we were coming home that night and Rob and I were talking about it and he was quite affected as well. And I said to him, ‘Why do you think we're so bothered by this one?’ and we came to the conclusion that it was that it was the lethality. That it was that thing about it can kill you, you know, it's like what we went through with COVID, when the fear starts to just sort of settle down a little bit and you get a bit further away from the threat, complacency can kind of set in and you can start to feel like, you know, it's going to be ok.

Kellie [00:16:43] It becomes your new normal.

Charlotte [00:16:44] Yeah and, you know, I haven't got the guillotine right above my head. And then you get that sort of trigger and it just feels like somebody wheeled the guillotine back into your room and set it up next to your neck. Yeah, it was really destabilising for a while. I went out, we've got a swing in our garden, and I went outside that night and turned on Olivia Newton-John music loud in the garden. And swung on the swing and let the tears flow.

Kellie [00:17:20] I'm sure a lot of people did that because even though they knew it was coming, it always seemed that little bit further away. And she'd been living so well with it for so long.

Charlotte [00:17:29] And a lot of people said to me, it was really interesting in terms of there were kind of two responses. One was like, but she had so long and yeah, I mean, sure, she did live with metastatic disease for a long time and longer is often better or considered to be better. But I think that was also part of the horror, was that it didn't matter how long it was, it still came back and it still took her life. And so is that sense of like longer doesn't make you safer. And that can feel very much like the sands shifting beneath your feet. I think the other thing that a lot of clients reflected on was that Olivia had access to everything. She had kind of unlimited resources. She had access to her own cancer centre. Even with all of that, even that didn't save her. And I think that was the other message, was that it kind of like, it doesn't matter, it's going to get you. And that again, really does prick that big vulnerability spot in us where it doesn't matter what I do, if it's going to happen, it's going to happen.

Kellie [00:18:34] I wonder also, Olivia Newton-John was very authentic, but she was also able to control the narrative of what people saw. And we didn't really see the bad.

Charlotte [00:18:47] No, no, that's right. And I think that's a good point, because in the absence of information, human beings will fill that hole, if you like, with their own version of events. Now, that can be a more positive version, can be a more negative version. But it also means that we come up with our own version of what the end of her life might have been like. That also can fuel anxiety.

Kellie [00:19:12] Okay, scanning anxiety. We touched on it. In the lead up to a scan, even if you know that it might be anxiety coming, what can you do? Is there anything you can do?

Charlotte [00:19:22] Not an awful lot. I mean, what I say to my clients is basically, you know, saddle up and get ready for a fairly rough couple of weeks. It can be helpful to let those around you know, because often, particularly the further you get away from diagnosis and for example, if you are living with metastatic disease, it can become kind of fairly routine. And nobody perhaps in your network of support is necessarily reacting to the note in the diary or the memo on the calendar that says I’m meeting with my oncologist or, you know, an MRI or whatever. And it can be helpful to just let them know that in the couple of weeks before those results, I'm probably going to be a bit toey. I'm probably going to be hard to live with. Not much we can do about it. Maybe just a little bit of, you know, extra leeway might be helpful for all of us. And the other thing, you know, that's the silver bullet I talked about it a lot in the first series is exercise. If you are feeling anxious and you know that you've got to wait for the appointment for the investigation and then you've got another wait before the results. You know, as much exercise as you can reasonably fit in is going to help. It's not going to take the anxiety away, but it's going to keep it from perhaps boiling over.

Kellie [00:20:36] Okay. What about a new treatment? It doesn't matter whether it's a new pill or chemo, something new when it comes to treatment that's going to cause some sort of anxiety.

Charlotte [00:20:47] Yeah. And I say this a lot, and if I had you in my consulting room, I would draw a picture of this. So I'm going to try and explain the picture, the pattern that emerges with new treatment anxieties essentially reflecting that every time you start a new treatment, most people experience a spike in anxiety. And sometimes they wonder why because they sort of feel like why haven’t I got the hang of this yet? I've done chemo and by the end of chemo I was almost like a chemo expert. I knew my side effects, I knew the rhythm and the routine but then I started radiation and I was anxious all over again. And we see this and it's really common and I think it's partly because each new treatment is something we've never done before unless you're living with metastatic disease. And so you're going back into another new environment with new staff, with a new schedule. You know, chemo is often days or weeks apart. Radiation is every day. Hormone tablet is one tablet a day. Each one is very different. And the way that I guess I see this is almost like a I call it a Sawtooth ridge, which is kind of like a zigzag. So every time you start a new treatment you have a spike and the line goes up and then you get used to it and over time the line goes down and you start to feel more comfortable, like I've got the hang of this and I know where to go and I know where to park the car and I know the name of the girls on the admin and I do my treatment and then I go home and get a coffee on the way and I don't feel too bad and I'm just getting comfortable. And then that comes to an end and I’ve got to start the next treatment and the spike goes up again. And so what I guess what it reflects is that we don't get the benefit really of much learning from each kind of treatment experience. And it can feel very much like every time I'm going back to zero and that again can feel like I'm not making progress, even though arguably I am progressing through treatment. You know, most of us experience a cancer diagnosis in our middle years, which means we've been around the block a few times. You know, we've perhaps had a few jobs, we've had a few relationships, we've had the opportunity for a lot of learning, and we get better at doing things with repetition. And I think perhaps on some level our brain goes I should be getting the hang of this and I still feel like I'm floundering. I still feel like I'm at sea.

Kellie [00:23:09] The impact that your cancer diagnosis has on family must be big.

Charlotte [00:23:14] Yeah, and this is where particularly for mums, but even for people who are perhaps managing the care of ageing parents, they really feel, like women are so good at guilt and really good at prioritising other people's needs, they really feel often quite strongly that they want to keep things as normal as possible for everybody else and they and they feel quite anxious about the impact being worse on their children and ageing parents in particular, sometimes their husbands, but mostly their children and their ageing parents. The difficulty that this then presents is that they can go to some extraordinary lengths to keep things as normal as possible while they're going through treatment and during post-treatment adjustment, and that can place an extraordinary additional burden on them at a time when they are already feeling physically and psychologically really burdened. Again, it's one of those things that is often not really spoken about. You know, they're busy. Women are often busy just trying to keep all those balls that are typically being juggled all in the air. You know, I want to still make sure that I pick up the kids from school or that everybody's got a decent lunchbox and nobody's having too much takeaway, I'm still visiting my parents every day or every second day. And the difficulty with this is that it can be setting yourself a very high bar, which if you aren't able to achieve and maintain, you then feel messages of failure and disappointment. And you can also find that the anxiety that you're feeling is actually worse. Because if you've built a belief that the only way we can all cope is that we keep everything as normal as possible but when you aren't able to keep it all as normal, as normal as possible, it can feel like your system is going to break. Now what I've seen is, and this is not always the case, and I don't want to be glib about it, but what I have seen is that children and ageing parents and even husbands are often more resilient and flexible than perhaps we either give them credit for or imagine they possibly could be, and that for a period it is completely okay for things to go from, let's just say a distinction level where everybody's having a really very comfortable life and all their needs are met all the time, to just a pass. And if that has to go on for six months or 12 months or possibly longer, it's going to be okay. Sure, it's not going to feel comfortable and they may even from time to time be some raised eyebrows or some whining. But I think everyone getting comfortable with the fact that this is a really big thing and responding authentically to it being a really big thing is actually much better than pretending that it isn't.

Kellie [00:26:06] So anybody listening to this is saying, you're right, you're absolutely right, but it’s actually doing it, handing it over. So when someone is diagnosed, or a recurrence or something that requires a change in life, quite often there's usually a lot of offers of help. So that that's not the problem. But still being able to let go of those reins. What do you suggest, is it compromise? I mean, you won't find many mothers lying in bed or just going ‘over to you’.

Charlotte [00:26:41] No, and it is often the case that unless they are talking to someone, perhaps like a therapist, that this stuff doesn't necessarily get challenged and that it kind of does keep going a bit like the boiling frog where you're the frog in the water that just gets hotter and hotter until one day you're actually cooked and you didn't really understand that that was what was coming. So what I mean by that is that it gets to a point where, you know, things are breaking and the burden becomes simply too much to carry. And then people have rather than what I would call a controlled explosion, they have an uncontrolled explosion. And that's never good. So for people listening, if you're feeling the pinch or if you're feeling like, you know, gosh, it's taking so much more out of me than it did before diagnosis to keep all these balls in the air, then that is worthy of pause and that is worthy of reflection and thinking alright, well, maybe it's about identifying perhaps what's desirable from what's essential. And with kids and possibly even with ageing parents, particularly parents who are really struggling to live independently, my bottom line, and it's a pretty low bottom line, but my bottom line with this stuff is risk and safety. So if you need to be present, involved, responsible, it is around making sure that those people that you care for, that their risk and safety is not compromised. But there's a lot of stuff that is well beyond risk and safety that falls into what I call the desirable camp, and that is very much around those sorts of things, like having all of their needs met all of the time, having all of their social and extracurricular activities, you know, just as they were pre diagnosis and treatment. If it means that, you know, some stuff goes through to the keeper and they don't show up for some stuff or that other people take them or pick them up or again, not trying to be glib, but if they do have some takeaway or have a lunch box that has way too many artificial things in packets, that's okay because it's temporary. We're not talking about a situation that is going to mean that you have to lower your standards for the rest of your life. This is about recognising that treatment and the early years post-treatment are really tough and making room and allowance for that is likely to be better for the person going through that cancer experience, but actually is going to be better for their family as well.

Ad [00:29:12] BCNA’s Online Network is a friendly space where people affected by breast cancer connect and share their experiences in a safe online community of support and understanding. Read posts, write your own, ask a question, start a discussion and support others. You're always connected, which means you're never alone as our Online Network is available for you at every stage of your breast cancer journey, as well as your family partner and friends. For more information, visit bcna.org.au/online network.

Kellie [00:29:52] Okay, So anxiety and sexuality, it's a really big topic and we covered it quite a bit in series one, episode eight and Charlotte, you were very honest and giving in your sharing of information.

Charlotte [00:30:06] Yes. For those who might not have listened to Series one or to that episode, just for context, I had a double mastectomy and that obviously changed my body and that then led to some adjustments in my sexuality and intimacy relationship with myself and my husband. And we do get into it in a fairly real way.

Kellie [00:30:30] There's probably a few people going ‘eek!’ But, you know, we go there, so let's go there about the sexual anxiety because it's real for a lot of people.

Charlotte [00:30:40] It is. And I guess there's probably two parts to it. There's anxiety around the physical act itself in terms of will it work and will it hurt? And we did again, talk a lot about that in series one, I think it was maybe episode eight, and that's where I actually do recommend some strategies to explain why things might hurt and not feel like they work the way that they used to. The other one is about feeling the fear of rejection, and this is really common and it does particularly relate to the experience of perhaps feeling like your body may look different and that might be about scars, might be about the loss of breast tissue, it might be about weight changes and hair changes, about all sorts of appearance type things and about the fear that you are no longer desirable as a woman or a man. And it's palpable. And it is also one of those things that brings out one of the very common anxiety responses. The two common anxiety responses behaviourally are avoidance, which is staying away from things that make us feel uncomfortable, and reassurance seeking, which is where we try and seek from others the reassurance that everything will be okay or that everything is okay. And sexuality and intimacy probably does both. We don't have sex, we don't get intimate because we don't want to risk the rejection or the pain or the fear that it won't work. But the other thing and this did happen to me, is that we can then overdo the reassurance seeking.

Kellie [00:32:16] Can you give us an example? Because I think there's going to be a few ‘aha’ moments.

Charlotte [00:32:20] Yeah, I mean, reassurance seeking is one of those things that when I describe it or explain it to someone in therapy, you can see a little penny dropping moment and then they'll go home and in the weeks between that session and the next, they kind of have a lot of moments where they realise, Oh goodness, this is that thing Charlotte was talking about. And almost always that come back the next session and go, ‘ you know that reassurance seeking thing you were talking about? Oh my God, I do so much of it. And I had no idea’. And we do it in all sorts of ways. Sometimes we do it really explicitly, like, do I look good in these jeans? That's reassurance seeking. Sometimes we do it in ways that we set up a test, so we set up a test in our relationship with someone to see whether they still love me. So if I say to my partner, you really might need to change your deodorant because you do not smell good. That's not really because I care about how they smell necessarily, it can be because it's my version of having a little go at them to see how they respond. And if they respond in a positive, perhaps humorous way, then I feel safe and secure in that relationship. Some people will feel it’s like to provoke a fight, but it's a test, and that's reassurance seeking.

Kellie [00:33:38] Poking a bear.

Charlotte [00:33:38] Poking the bear to see whether the bear bites you. And if they don't, then it's a sign that everything is good. And if they do bite you, it's perhaps a sign of like, you know, you were testing to see whether things were as you thought. But the way that it manifests or does manifest sometimes in around sexuality and intimacy and it did for me was that I started to say to Rob, ‘you couldn't possibly find this sexually appealing anymore’, ‘You can’t possibly find my chest in any way desirable whatsoever’. And I would make it as a statement. But it wasn't a statement. It was a statement with me watching him and I was watching and I was listening for a response. And I did it over and over and over again. And I knew what I was doing and I did it anyway. And after a while I got really sick of hearing it because he would do what Rob would do, which was say, Darling, I love your broken body. You know, I always will. Well he would say it better than that. He would say, I love your body, I love your broken body. And that worked really well. But I still kept doing the reassurance seeking. So the problem with reassurance seeking is that it's a bit like a drug. The more that you have it, the more that you feel you need it. And what tends to happen is that the interval between seeking reassurance gets shorter and shorter. And so in a medical context, it can be like getting a scan and being comfortable with getting a scan once a year, but then feeling like you need a scan once every six months and then once every three months. In a relationship context, it can be like I was doing with Rob, asking for reassurance that I was still desirable and needing to do that, you know, not just once a week, but once a day. And that, of course, makes the anxiety get worse, not better.

Kellie [00:35:27] And I think for anybody when someone says, do I look good in this? Just about everybody knows they're not actually really asking you for the truth and they're not going to say, actually, it would look better if you did this.

Charlotte [00:35:40] That's right. You think you're asking for the truth but you're not really.

Kellie [00:35:43] So everybody knows that. So there is that that role playing because no one in their right mind is going to turn around and give you the utter truth, so if we're all a bit in on the game. Then what's the solution here?

Charlotte [00:35:56] Well, what I did and what I reflect on occasion to clients is that I decided to trust him. I made a decision, and it was a bit weird because It felt incredibly like it lifted a burden off my shoulders. And it does sound odd, and I completely get that some people would go, oh come on you can't just make a decision to trust him. But I just did. I don't know whether it was because I'd asked him enough times, like I must have asked him 100 times. But I did just go do you know what? I mean he's my guy. I trust him with my life. I trust him with my money. You know, I trust him with anything. So why wouldn't I trust him with this?

Kellie [00:36:44] So you still asked the question but decided to trust him. You didn't stop asking the question?

Charlotte [00:36:48] Yeah then I stopped asking the question. And from that moment, and that was probably sometime between the last time we recorded and now, sometime in the last 15 months. Do you know what I think it might have been quite close to when we recorded last time, because I worked through a fair bit of stuff in the first series. But yeah, no, I decided to trust him and I have never asked since then and I believe him enough. I don't know that I need to believe him any more than where I'm at.

Kellie [00:37:16] For argument's sake, if you don't have a partner, but that's what you're thinking in your head. So you talking to yourself, is it about having that conversation with yourself as well?

Charlotte [00:37:25] It really is. Because that's ultimately what this is all about. It's not really about whether Rob finds me desirable or not. If I can believe that my body is still desirable as a woman, I can do a jiggle in my undies. You know, I can go I'm ready for a bit of va va voom. Any amount of somebody else telling me that isn't really going to do anything. So, yes, it is about having the conversation with yourself. And if you can get there, getting to a place of acceptance. And I think it’s a bit like what a lot of women have to confront with natural ageing, you know, even if you've never been through a cancer experience, there’s a whole bunch of stuff that happens to all of us women, men, everybody as you get older and none of it's very glamorous. It all jiggles and it all goes south. And so I think in some respects, you know, it's kind of an accelerated version of some of that stuff. And it is really helpful. And I've seen people like Jamie Lee Curtis on Instagram talking about this stuff recently where it's kind of like, look, you can spend a whole lot of time wishing it were otherwise and doubting that you are, you know, worthy of desire. Or you can go, do you know what? I can rock a scar, I’m alright in my undies.

Kellie [00:38:46] Little bit confronting and a definite anxiety response for those who want to re partner.

Charlotte [00:38:56] Yes, And this really applies, I think, more commonly, certainly not only, but more commonly to women who are diagnosed at a younger age, women who may not have had a partner or who maybe perhaps had just been in the kind of the dating scene, as it were, and feel very worried about what the diagnosis and potential long term health implications might mean for partnering and having a family and a future together, perhaps in the way that they'd always imagined. And some of that's around what we were talking about before, about things like desire and, you know, fulfilling the kind of stereotypical form of a female. But some of it's also about the idea that people can feel like they have less to offer. They can feel like they're damaged goods, and that if people know about their cancer, that it might affect their assessment of that person as a mate, as a person to spend their life with. And I wish I could say that we lived in a world where none of that happened. But I mean, the reality is that it does. It doesn't happen all the time and I'm not even sure that it happens in the majority of cases but I mean, I couldn't sit here and say that it doesn't ever happen. There are some partners, potential partners, male, female, nonbinary, who would find the changes in someone's body or the risk that they have to live with for the rest of their life, might be something they might just feel they're not able to take on. And that doesn't make them a bad person. That just means that that's not something that they feel they can do. And to be perfectly honest, if they feel they can't do it, they probably shouldn't. But it does then, you know, play into the anxiety of particularly a young woman who might feel like, well, what does that mean for me and is there anything I can do about it? And I think what I always come back to is that there very well may be a person or perhaps even more than one person for you out there, but if they aren't up for the challenge, they aren't able to cope with the changes to a person's body or the changes to a person's medical risk profile, then they're not your person.

Kellie [00:41:21] It might also be not just what has happened. It could be the risk of what might happen.

Charlotte [00:41:28] Exactly, and that's that sense of like, I guess in some respects maybe it's a little bit like partnering with someone who might already have children. You know, it might be that sense of like, do I want to take that on? Do I want to be a carer for someone? What If the cancer comes back and I'm suddenly looking at a life of metastatic disease? Do I want to be, you know, signing up for that? And it's different if you are in a relationship, a mature relationship, or a marriage where you know, you've made the big, for better or for worse sickness and in health kind of vow and you're in it up to your eyeballs with mortgages and kids and all of that. I mean, it's not easy, but I think that commitment's already been made. But to take on the commitment at the front end when it is declared and it usually is at the beginning, I mean, it isn't necessarily a small thing. And I think again I come back to if it's not something that another person feels that they're up for, then they're not your person.

Kellie [00:42:33] So and of course, while we talk about reassuring yourself and talking to yourself, there's always places like BCNA’s, Online Network and there is specifically a group for young women with breast cancer to sort of narrow it down a bit specific to those unique challenges.

Charlotte [00:42:52] Absolutely. And I mean, you know, this, again, is it's a big topic, but it goes beyond partnering. It goes into, you know, will I be able to have a family? Because the fertility challenges that often come as a result of cancer treatment, particularly as a young woman, for example, when I was diagnosed, I'd already had my four children. So, you know, the fertility stuff is just not even vaguely relevant to me. But if you're a young woman who had imagined and planned a family and suddenly you're confronted with either maybe not being able to do that the conventional way or having to really get creative about how you might do it, that’s whole lot of anxiety there.

Kellie [00:43:37] It all plays into self-confidence, doesn't it?

Charlotte [00:43:39] Yeah, lots and lots of self-confidence stuff and we see a big drop in self-confidence after diagnosis and treatment. And in fact, we've got one whole episode, this series, which is about returning to life. We call it re-entry Wobbles. And so you hear a lot more about that in a few more episodes time.

Kellie [00:43:58] Is there a one size fits all when it comes to anxiety and breast cancer?

Charlotte [00:44:04] No. As with everything to do with cancer, it is so individual. Having said that, the anxiety that's connected to being what I call an outlier, which is when the rules don't apply to you. And so that's when your particular diagnosis and sometimes treatment, but mostly diagnosis is kind of more interesting than most. One thing that we often say is you don't want to be interesting to your oncologist. You want to be garden variety. You want to be, you know, middle of the road and not everybody is. And when you are not middle of the road, that can present additional anxiety challenges because there can be a sense of, well, if that very unusual thing happened to me, and it is often around being very young on diagnosis because you don't fit the he profile of the middle aged woman who's already had kids. If you're 30 and you're diagnosed with cancer, that is being an outlier. And if you're a man, you know, you are definitely not to the middle of the road. Sometimes the other way that people are an outlier is if their diagnosis, the particular characteristics of their tumour, of their pathology in their tumour is kind of unusual or different, It can leave us feeling more isolated and more anxious because we feel like the rules don't apply to us. So anything that my medical team or the research, the literature, the database around cancer is telling us kind of doesn't apply to me the way that it does to the majority of people. And it usually means that we feel more scared because we think, well, if that one bad unbelievable thing could happen to me, then why would I believe that it couldn't happen again? That a second or third really bad, unbelievable thing couldn't happen to me. And this is something that I work with very, you know, slowly and gently in therapy. But essentially what we're trying to do is see whether we can look at it from the other perspective, which is that if you're an outlier, it can mean that you are unusual and different. It does mean that you're unusual and different, but not necessarily always in a bad way. So it could be that just as it was rare that this thing happened to you, it could also be rare that a good thing happens to you. So it doesn't always have to be that one bad thing follows another bad thing is an outlier. It could be, and this is hard to get your head around. Could be that a good rare thing happens after a bad rare thing.

Kellie [00:46:34] Okay, does sound hard. And it also sounds hard when because breast cancer is fairly common. That usually also provokes really common responses of like, oh, my aunt had that and she's fine. You'll be fine. The treatments are amazing now. Whereas for some things like triple negative breast cancer, there aren't as many treatments.

Charlotte [00:46:56] No, that's right. And that's where the isolation thing is such a big part of being an outlier. It's the double whammy of feeling isolated and anxious because that feeling of people don't get it, they really don't get it. And exactly as you say, there's a lot of awareness about breast cancer. There's a lot of people who have breast cancer. And there can be the tendency to kind of go, you know, everyone has a version of the same experience and that just isn't the case.

Kellie [00:47:22] Let's get to FONEBO.

Charlotte [00:47:29] I love FONEBO, most of my clients latch onto it, it's easy to say. fear of negative evaluation by others FONEBO. We all have FONEBO in lots of parts of life. And again, it's not necessarily a bad thing as long as there's not too much of it. And it's very easy to say, Oh, we shouldn't worry about what other people think of us, but most of us do. I often quote Brené Brown when I'm talking about FONEBO which is essentially when you distil it down where Brené says try and identify the people in your life whose opinion really does matter and it should be a small number. And I've done that exercise and my number is three, plus or minus four. So the three people whose opinion really matters to me, my husband, my sister and my best friend, and in the plus or minus four is my children, sometimes I care what they think and sometimes I don't. And sometimes that's really helpful to just be able to refer back in my mind to that list. If I'm getting a bit kind of anxious about, you know, what other people might think of me or what I've done or what I might do or whatever, and then to just think, Do you know what probably doesn't really matter. FONEBO can manifest in a cancer experience in all sorts of ways. And one of the ways, we’ll talk about in the next episode, is in relation to your medical team, and it can be particularly tricky if you're part of the LGBTQIA+ community where your lifestyle choices and who you are as a person may not sit so comfortably with everyone around you, and that may be because you're suddenly in a medical context, whereas, you know, you're not used to brushing shoulders with those people all the time.

Kellie [00:49:01] What is the downside of that? Do you tend to not disclose everything which could, you know, have a domino effect?

Charlotte [00:49:08] Yeah, absolutely. And it can play into that avoidance behaviour that we were talking about before. We stay away from the thing that makes you feel uncomfortable and it can be incredibly invalidating because if that's who you are as a person and you're not able to express that and you're having to avoid acknowledging who you are as a person, that can set up all sorts of psychological dissonance, we call in your head where you're trying to like, manage difficult thoughts that don't have a solution.

Kellie [00:49:34] So is it okay? Is it enough to be aware of it?

Charlotte [00:49:38] The awareness is really important, understanding that most of us have a level of FONEBO and that exercise around working out whose opinion really does matter. Now there are circumstances and again, we'll talk about the medical one in the next episode, but if your boss has a poor opinion of you that actually potentially can really matter, if your bank manager has a poor opinion of you that can really matter. So it's naive to think that, you know, we should be not bothered by what other people think of us. But again, it's about how much we let that impact the general functioning of our lives.

Kellie [00:50:14] And finally, body image, anxiety about body image. We sort of covered that a little bit.

Charlotte [00:50:19] Yeah and we did a whole episode. Episode four in series one was all about body image. It's a very specific anxiety and it is a very specific form of FONEBO so very specific form of fear of negative evaluation by others of my body. You know Am I going to be considered still to be a woman, still to be female? Am I going to still be considered to be desirable? We talked about that. Am I broken? Am I damaged? Am I a freak? Those sorts of thoughts are really common.

Kellie [00:50:52] So we're looking for that Goldilocks anxiety. Not too much, not too little.

Charlotte [00:50:57] Just the right amount, just the amount to keep you safe. And that's the thing about anxiety. It's your internal burglar alarm. It's there to keep you safe. We don't want to disable it because what happens if you turn off the burglar alarm? all the burglars can get in.

Kellie [00:51:11] And we don't want that. Wow. It's so broad anxiety, isn't it? And you've touched on just a few. Are there some strategies?

Charlotte [00:51:20] Yeah. I mean, I think the first thing to recognise is that cancer provokes anxiety and that's normal. Some of these things will spike and recover in a matter of hours and sometimes days. When you're dealing with things like waiting for results, you're going to feel anxious for as long as it takes to get the results. There are grounding techniques and things to do in the moment, like breathing and meditation that can bring you off the boil. But getting to know your anxiety and getting to know what your triggers are is really important because then you start to feel a bit more like you're in the driver's seat rather than the anxiety being in the driver's seat and scaring the crap out of you when it feels like. And learning to sit in the discomfort. We are always in search of less discomfort, but being able to kind of acknowledge that, okay, I'm having an anxiety moment. All anxiety is temporary, it will pass. And if we fight and flight, if we flee, we often actually exacerbate the anxiety. Whereas if we just settle into it, ride the wave, understand that it will dissipate with time and usually not as much time as we think. That can be a really powerful management tool, because once you start to understand that it doesn't have the better of you, then you're not likely to get anxious about your anxiety.

Kellie [00:52:46] Wow, that was a big one. Thank you for that. And to our listeners for joining us on our first episode of Season two. As we said, it's great to be back and we're really looking forward to discussing many more interesting topics in the coming episodes. Always thanks to our podcast supporter Sussan. If you found this chat helpful, please share it with someone you know. Don't forget you can subscribe to ensure that you never miss one of these episodes in this second series, and we'd really love to know what you think. So please leave us a rating or review and tell us what you enjoyed about it. Our theme music is by the late Tara Simmons, who was passionate about music and creating breast cancer awareness.

Coming up in episode two of What You Don't Know Until You Do Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman, we're going to take a look at the instant relationship of trust you forge with strangers who literally have your life in their hands. Of course, we're talking about your medical team. There's the good, the uncomfortable and imbalances. Dr. Charlotte's going to talk about the expectations that you didn't even know you had, vulnerability and Self-Advocacy. Episode two, Forged in Fire. Looking forward to that one.

Charlotte [00:54:00] Absolutely, can’t wait

Kellie [00:54:00] You've been listening to Upfront About Breast Cancer, What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. I'm Kelly Curtain. Join us next time.

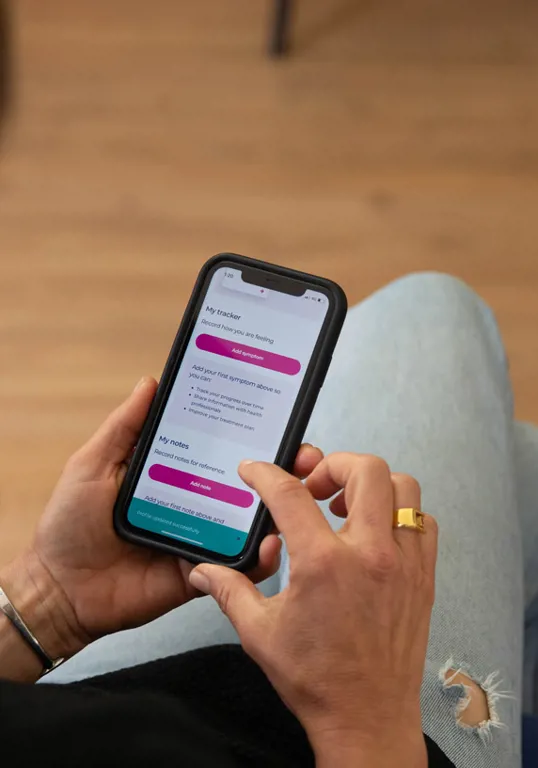

Ad [00:54:12] Looking for practical information to help you make decisions about your diagnosis, whether DCIS, early or metastatic breast cancer. BCNA’s My Journey features articles, webcasts, videos and podcasts about breast cancer during treatment and beyond to help you, your friends and family as you progress through your journey. It also features a symptom tracker to help you manage the changing symptoms you may encounter during your own breast cancer experience. My Journey. Download the app or sign up online at myjourney.org.au. Coming up in episode two of Upfront About Breast Cancer – What You Don't Know Until You Do: Unlimited with Dr. Charlotte Tottman. Forged in fire: Relationships with your medical team and self-advocacy.

Charlotte [00:54:59] I am going to feel vulnerable in addition to already feeling vulnerable because I've been diagnosed with cancer and I'm going through treatment. You get into a medical environment in the context of a cancer diagnosis and you can really feel on the back foot. Learning where you want to get things like your emotional support from can be really helpful. So if you feel like I need to feel like I matter and I really need to feel like someone cares about me, and if you don't feel like you're getting any of that from your surgeon or your oncologist, I would say that's still a problem. But if you feel like they're the only person that you're looking to meet that need, then again, you might be setting yourself up for failure. So it's about recognising, okay, do I want to get my emotional needs met from my surgeon or do I want to get my surgical needs met from my surgeon? We want to tap into the fact that we've got two minds, we've got an emotional mind and we've got a wise mind. But it can be really helpful that if you're feeling an emotional response in the moment when you're perhaps sitting in front of your medical specialist, it can be helpful not to react in the moment to that, to actually note down what it is that was bothering you to make a list. It might only be a short list, but to actually write it down. And that makes sense of it. And it means that you are engaging your rational mind. And then if you act on that, you're much less likely to be having an emotional response.

Ad [00:56:23] This podcast is proudly brought to you by Sussan. Our theme music is by the late Tara Simmons. Breast Cancer Network Australia acknowledges the traditional owners of the land and we pay our respects to the elders past, present and emerging. This episode is produced on Wurundjeri land of the Kulin Nation.

Listen on